Archery in Early Modern Japanby Aafke van Ewijk

In eighteenth-century Japan, learning to shoot with a bow and arrow was part of the educational curriculum for samurai boys such as Genta, the protagonist of the Shudō tsuya monogatari. Although no longer used on the battlefield, the bow was still an important part of the samurai cultural heritage, and its use and proper form was formalized within a number of schools and their branches (ryūha). Legendary archers lived in the popular imagination and archery games were enjoyed by Edo-period samurai and commoners alike. Bows also continued to be used on ceremonial occasions to ward off invisible enemies. While most studies have focused on the various ryūha with their grandmasters and official archery events, Shudō tsuya monogatari sheds light on the way in which archery also functioned as a social activity for young samurai.

The Military Art that Produced the Bushi

Although in today's media representations it is the sword that appears as the samurai's weapon par excellence, the method of fighting that featured most prominently in medieval warfare and served to consolidate the bushi 武士 (warriors) as a social group was, in fact, mounted archery. As Karl Friday observes, from the eighth to the tenth century, military institutions increasingly relied on self-funded and self-trained cavalry rather than large troops of infantry, with battles consisting mainly of duels and skirmishes between small groups in which foot soldiers (armed with bows and polearms) fought alongside mounted archers.

Edo-period samurai looked upon the heroes and battles from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries as the "golden age" of the warrior.

Once Upon a Time…

[Yoichi] Munetaka took out his humming-bulb*, fitted it, drew his bow to the full, and sent the arrow whizzing on its way. … Singing until the bay resounded, the arrow flew straight to the fan, thudded into it an inch from the rivet edge, and cut it loose. The humming-bulb went into the sea; the fan flew toward the heavens. For a time, the fan fluttered in the air; then it made an abrupt descent toward the sea, tossed and buffeted by the spring wind. The red fan with its golden orb floated on the white waves in the glittering rays of the setting sun; and as it rocked there, dancing up and down, the Heike in the offing beat their gunwales and applauded, and the Genji on the land struck their quivers and shouted.

This is the way that Heike monogatari 平家物語 (The Tale of the Heike, 14th c.) describes the exploits of the legendary archer Yoichi Munetaka, better known as Nasu no Yoichi. Riding his horse into the waves, his feat of shooting a fan that had been placed on a pole on an enemy boat was admired by friend and foe alike. This idealized episode, which took place during the Battle of Yashima (1185), has been invoked countless times in literature and visual culture to the present day, as in the Heike monogatari emaki 平家物語絵巻 (Edo period) and the anime Pom Poko.

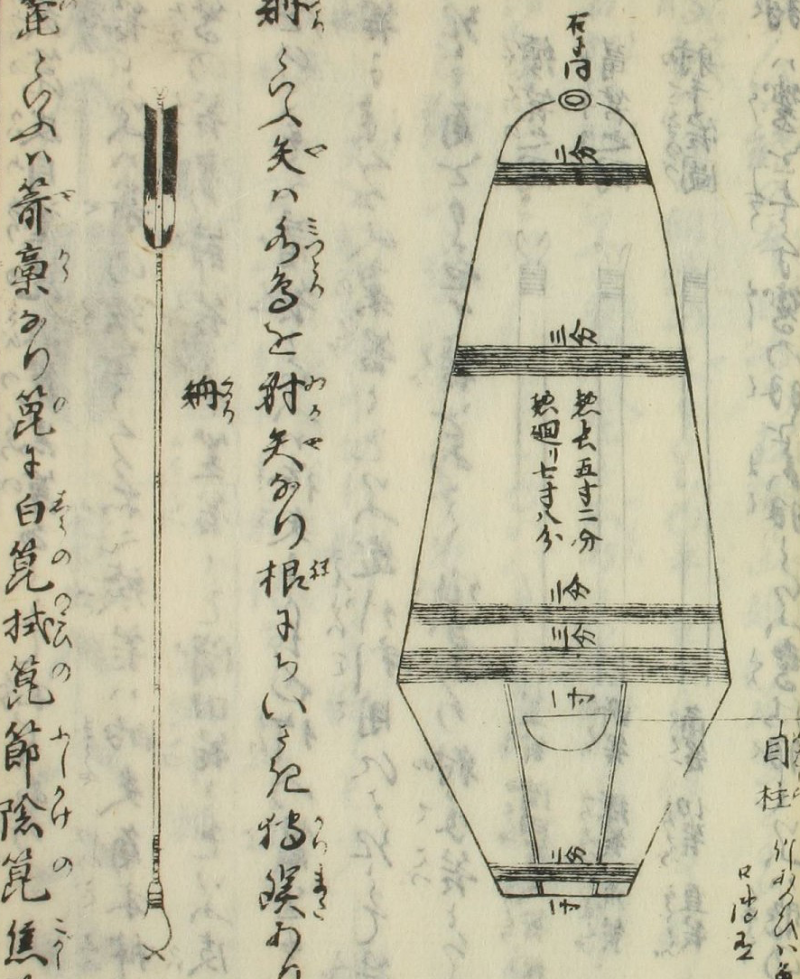

* Arrows with a turnip-shaped whistle attached to their tip were known as humming bulb (lit. turnip [headed] arrow; kabura-ya 鏑矢).

Humming bulbs were used in ritual archery exchanges before commencing battle and on ceremonial occasions, when both the whistle of the kabura-ya and the twanging of the bowstring were thought to ward off evil.

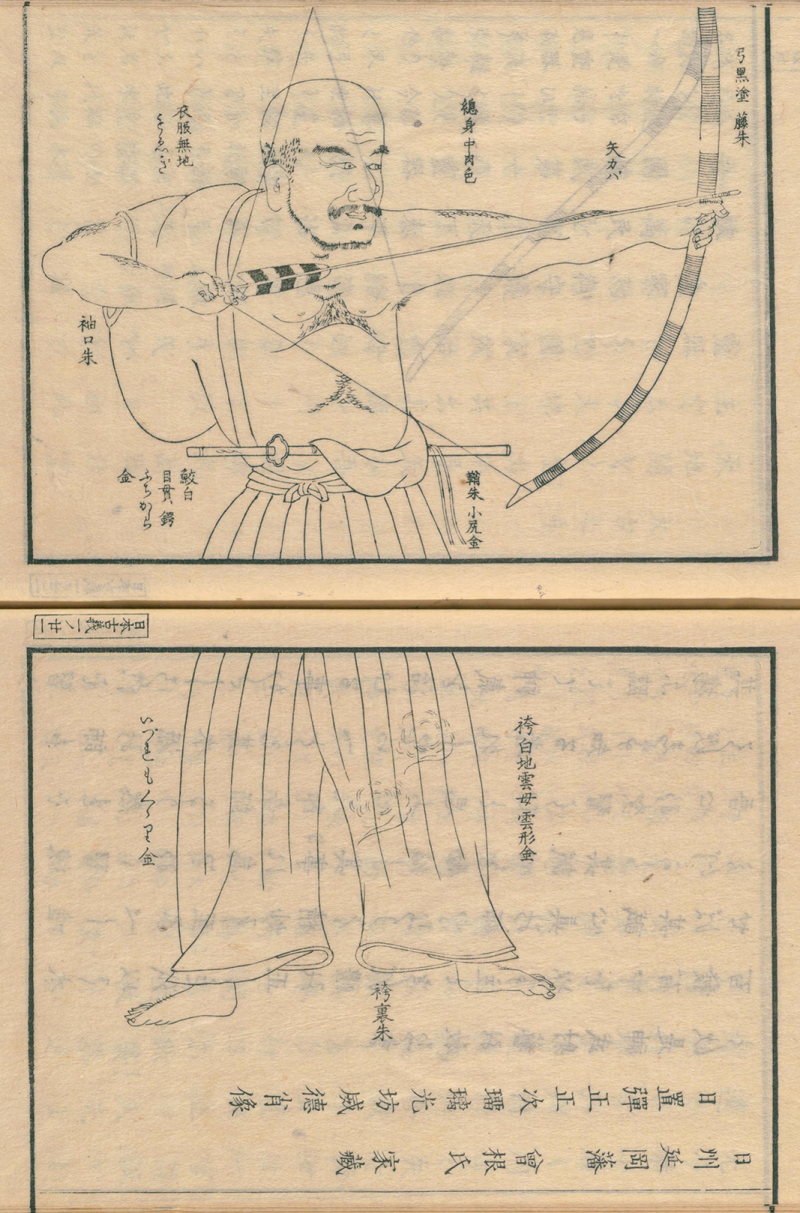

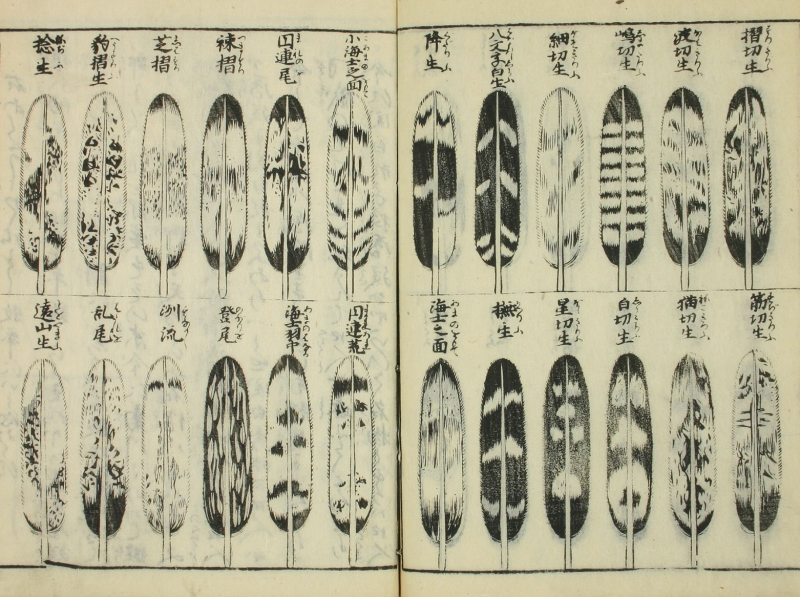

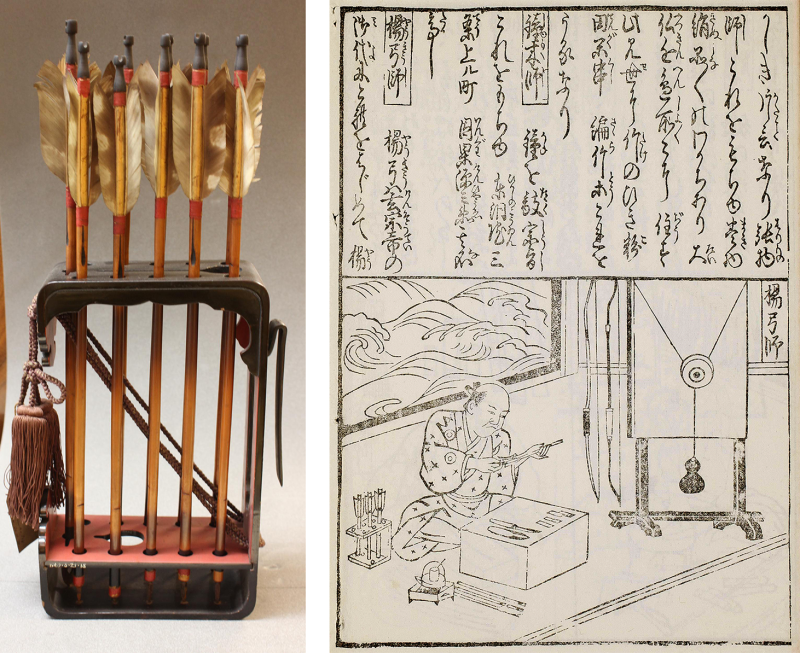

Buke chōhōki (Treasury for warriors) illustrates the internal structure of the humming bulb. Chōhōki, which can be translated literally as "records of weighty treasures," were a type of household encyclopedia. The second volume of the five-volume Buke chōhōki is fully dedicated to archery. It introduces history, legends and rituals related to archery, as well as more practical information about the bow and different types of targets, arrow tips and fletching.

Archery Rituals and Formalized Practice

The Kamakura period saw the development of various ritualized and training-oriented forms of archery, which can be divided into the two main categories of standing archery (hosha 歩射) and mounted archery (kisha 馬射). Archery ceremonies had first been introduced from China but they acquired their own Japanese character at the Nara and Heian-period courts. In turn, warriors during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods adapted court rituals for their own use, such as the annual yumi-hajime 弓始 (first bow) ceremony that was held on the seventeenth day of the first lunar month. The ceremony involved a standing archery contest between groups of selected archers with glory and rewards bestowed on the victors. The ceremony fell into oblivion in the sixteenth century until Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune 徳川吉宗 (1684-1751) instigated its revival.

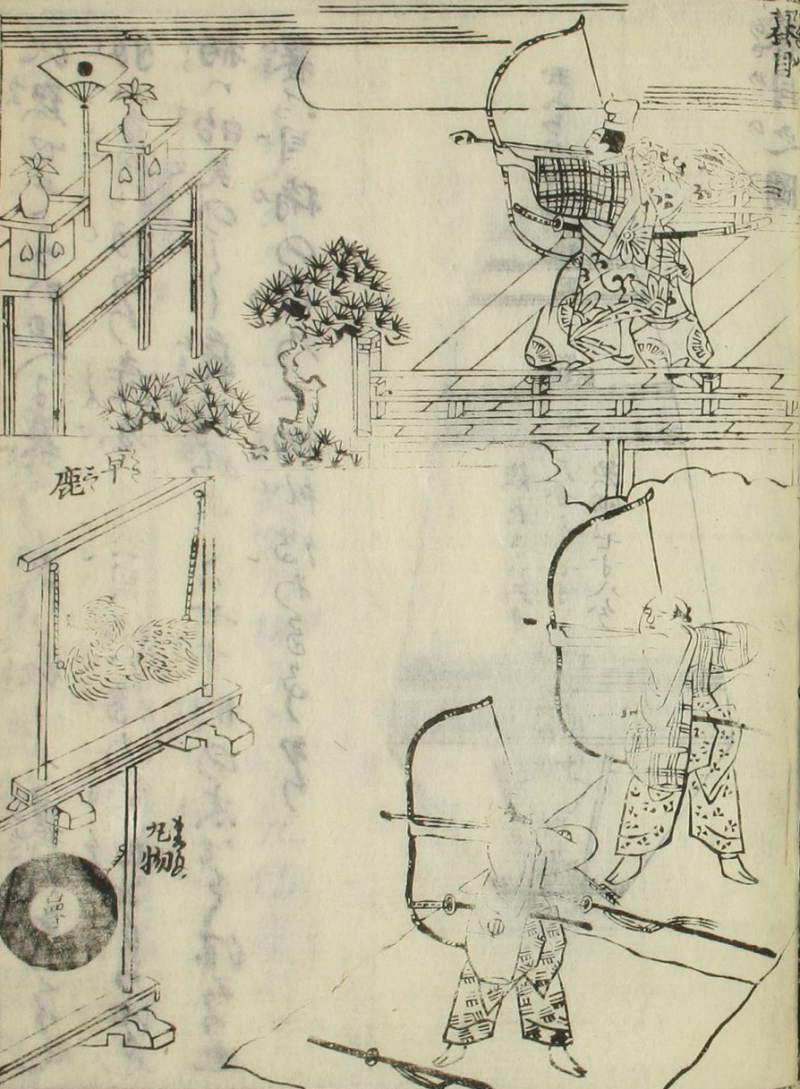

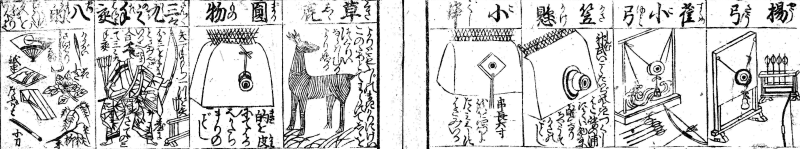

Various types of targets were invented for archery practice from a standing position as preparation for hunting and mounted archery, the most well-known being the "straw deer" (kusajishi 草鹿) and the "round target" (marumono 丸物 or 円物). The round target was composed of a wooden board, soft padding, and cow hide painted with a black circle.

The Muromachi period saw the appearance of the "small target" (komato 小的) for short distances, while the target hitherto used for long-distance archery (from around fifty meters) became known as the "large target" (ōmato 大的).

The small target was drum-like in shape and was made of cypress wood and paper, measuring 1 shaku 2 sun (about 30 cm) in diameter.

Kasagake, which was first practiced at the Heian court and became popular among the warrior elite in the medieval period, involved shooting at a target while galloping along a roped-off track.

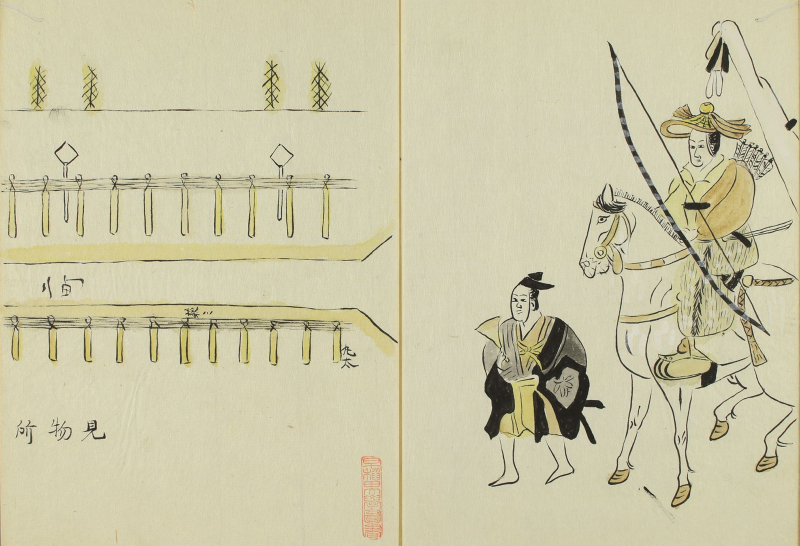

Yabusame was a highly ceremonial form of mounted archery that is still performed today at various Shinto shrines. As with kasagake, riders galloped along a track, but in this case they tried to hit three wooden targets on bamboo poles on their first pass and three small clay targets on their second.

This image shows a yabusame archer in ceremonial clothing on his way to the track, accompanied by attendants.

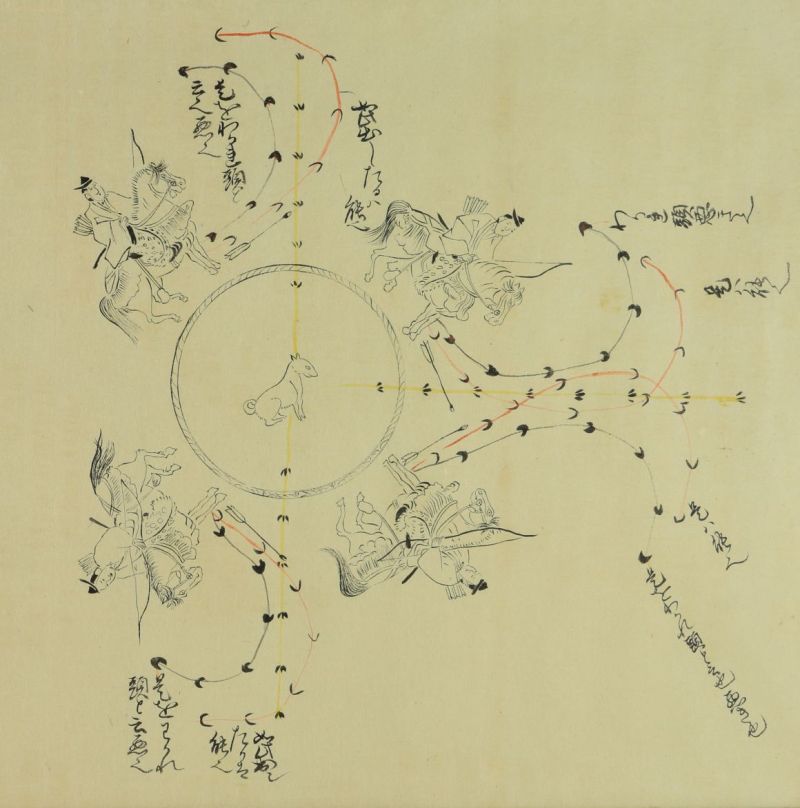

Inu-oumono was especially popular among the Muromachi-period warrior elite as a form of sporting entertainment as well as useful archery training with moving targets.

Teams of mounted archers took it in turns to fire arrows at dogs released into a circular enclosure with points allotted according to an intricate system that assessed an archer's skill and speed in hitting the targets. Although blunt arrows were used, the sport undoubtedly caused the dogs to suffer and, unlike kasagake and yabusame, this form of archery practice did not survive into the twentieth century. The manuscript Inu-oumono hin'i kisei introduces "graceful" and systematic methods for shooting the dogs in inu-oumono, which suggests that less well-trained riders were at risk of ending up in a chaotic scramble.

Martial Arts Schools and Training for Edo-period Samurai Boys

According to our manuscript, Genta went to the residences of three different teachers to receive instruction in the Confucian classics, Ogasawara etiquette, and archery. This was a typical arrangement for young mid-ranking samurai, and although not mentioned in the text, his education probably included other martial arts. Ogasawara-ryū 小笠原流 was a school of etiquette and martial arts that originated in the Kamakura period. The Ogasawara clan served Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199) and subsequent military leaders as teachers, although they were not yet recognized as a "school" (ryū 流) at that time.

In Yonezawa, there are records of licensed teachers from the Heki-ryū and its branches, the Insai-ha 印西派 and the Sekka-ha 雪荷派.

When commencing studies with an archery teacher, students typically had to sign a written oath, that they would respect the teachings of the ryū, train diligently, be loyal to their teacher (like a son to his father), and not defect to any other school.

The Gamification of Archery

That summer, shooting arrows at targets became such a rage that there was no one–young or old, man or woman–who did not take up archery. (...) At that time, even conversations in the evenings revolved around archery, leaving no room for any other topics. Indeed, it was as if you were barely considered human if you did not shoot a bow.

Although the increasingly stylized nature of archery training may have been somewhat dull, it is clear that archery enjoyed great popularity as a sport. We are told that Genta and his acquaintances spent their summer practicing komatomae 小的前 (shooting at a small target from a standing position), which was a typical pastime for young samurai of the middle and upper ranks.

Although Genta and his fellow archers may have attracted spectators as they competed at their target practice, it was tōshiya 通矢 or "continuous shooting" that came the closest to our concept of a sports competition.

Not everybody appreciated the ways in which young men indulged in archery. Hinatsu Shigetaka 日夏繁高 (1660–1731), the author of the well-known treatise Honchō bugei shōden 本朝武芸小伝 (A short biography of martial arts in our land, 1714), was appalled by their overt focus on competitions, record-setting, and "making good impressions on the eyes and ears of others," insisting that archers should focus on correct form and remember that this is the path to mastery.

Competitors in tōshiya would usually be financially supported by their domain as they required hundreds of arrows and several bows.

Every evening fourteen or fifteen people would gather at young Genta’s house to exchange bows and arrows and discuss selling them for money. Afterwards they would walk around the town clapping their hands just like merchants and farmers soliciting custom. Even though it is only natural that many people are practicing archery, they certainly shouldn’t behave like this.

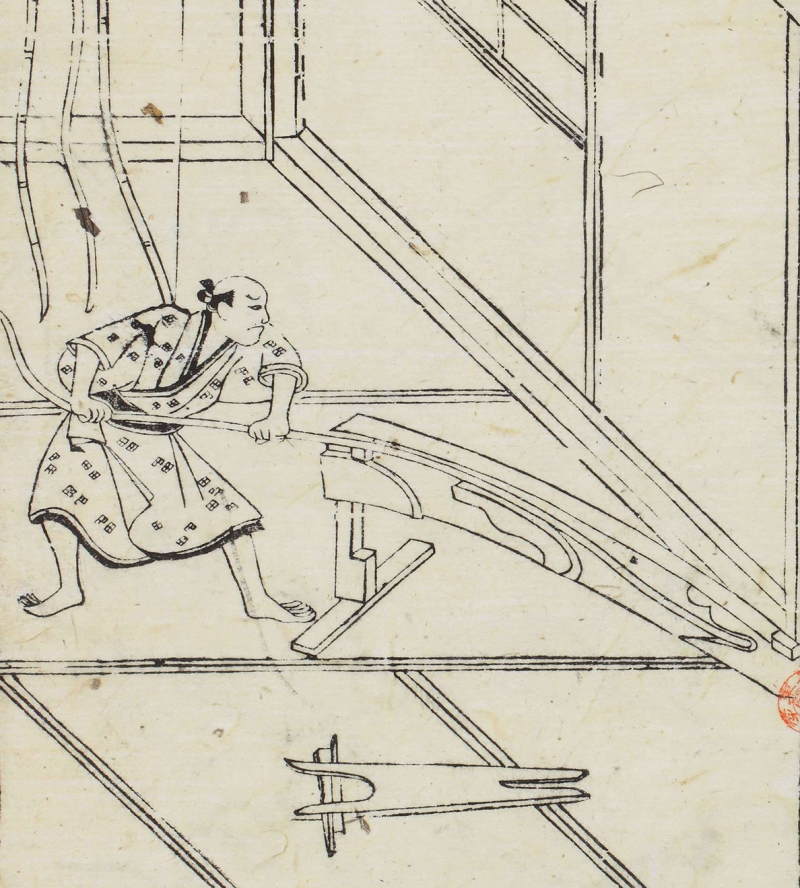

Bows were made of bamboo and wood that had been carefully dried and hardened by repeated exposure to air and fire. The parts were laminated together and wrapped in rattan in which wedges were hammered to bend the bow into the correct shape. After being left in this position for a considerable length of time, the bow was unwrapped, carved, and shaved until it attained its desired strength and form.

The illustration shows a bow-maker bending a bow on a haridai 張り台 (stretching block) in the opposite direction to the previous warp. When the bow was ready, a string would be attached that was usually made of twisted hemp and wrapped in washi 和紙 (paper) or thread and varnished with lacquer to extend its life.

For arrows, a smaller variety of bamboo known as yadake 矢竹 (lit. arrow bamboo) was dried, hardened by fire and shaved.

Archery was an important part of the education and cultural heritage of the samurai who appear in Shudō tsuya monogatari 衆道通夜物語. Whereas most studies of Japanese archery have focused on schools, technique, and ceremonial use, this manuscript introduces us to the more informal social function of archery as a popular summer pastime for young samurai in early eighteenth-century Japan, in which bows and arrows were discussed, compared, traded, and even used as a means of gaining another man's affection.

Indoor Archery Games and Shooting Galleries

Edo-period commoners also enjoyed archery games that had their origins in the pastimes of Heian-period courtiers. Two popular indoor games were yōkyū 楊弓 (willow bow) and suzumekoyumi 雀小弓 (sparrow small bow), in which "sparrow" refers to the small size of the target, which was only 9 cm in diameter and suspended by threads. They used small bows (koyumi 小弓) of willow or rosewood that were only 80 cm in length and strings that were designed for the biwa, a type of Japanese lute.

The two images on the upper right show targets for the indoor games yōkyū and suzume koyumi. From right to left there are also representations of targets for kasagake and ogushi no e 小串の会 (various objects attached to a skewer), a straw deer and a round target (without the ropes and frame). The accompanying text explains that the straw deer target was invented by Minamoto no Yoritomo for hunting practice and that kasagake was invented by Emperor Jinmu. The final two pictures illustrate targets for the New Year's mounted archery event sansanku tebasami shiki 三々九手挟式 (the three-three-nine arrows in hand ceremony) and the "eight targets" (yatsumato 八的) consisting of a sagebari 下針 (needle suspended by a thread), a shihan 四半 (a small board), a tatōgami 畳紙 (a folded piece of paper used for blowing one's nose or jotting down a poem), a knife, a flowering branch, and a willow branch.

All that you needed to play yōkyū was the necessary equipment and a largish room, much in the same manner as putting up a dartboard today. However, the late eighteenth century also saw the appearance of public yōkyū shooting galleries (called yōkyūba 楊弓場 or dokyūba 土弓場 in the Kansai region and yaba 矢場 in Edo).

They were located in urban areas in temple precincts or the pleasure quarters, for example in the Asakusa area and near Shibadai Jingū Shrine in present-day Minato ward, but were banned by the shogunate in 1842 for being "immoral."

The reason they attracted the attention of the authorities was that visitors were assisted by so-called yatori-onna 矢取女 (lit. arrow-collecting women) who picked up and handed over the arrows, but their actual trade was unlicensed sex work.

In this print from a series of parodies of famous warriors, Nasu no Yoichi is depicted fooling around with a yatori-onna. His famous fan target is attached to a pole on a miniature boat. Making fun of Nasu no Yoichi could be equated with making fun of the samurai class, hence the title's claim that the prints are intended merely "for the amusement of children."

Despite the ban, yōkyū galleries continued to exist well into the Meiji period.

Beyond the narrow confines of Genta's world of rural warrior martial arts and archery practice, urban commoners thus also reveled in the stories of legendary archers and their own, not necessarily wholesome varieties of archery games.

To cite this page:

van Ewijk, Aafke. "Archery in Early Modern Japan." Blood, Tears, and Samurai Love: A Tragic Tale from Eighteenth-Century Japan on Japan Past & Present. 2024. https://japanpastandpresent.org/jp/projects/blood-tears-and-samurai-love/introduction/archery-in-early-modern-japan

For additional information on references and images, see our bibliography and image credits pages. Research for this page was generously funded by the Dutch Research Council.