A Tragic Love Story in an Eighteenth-Century Manuscriptby Angelika Koch

The Tale Begins

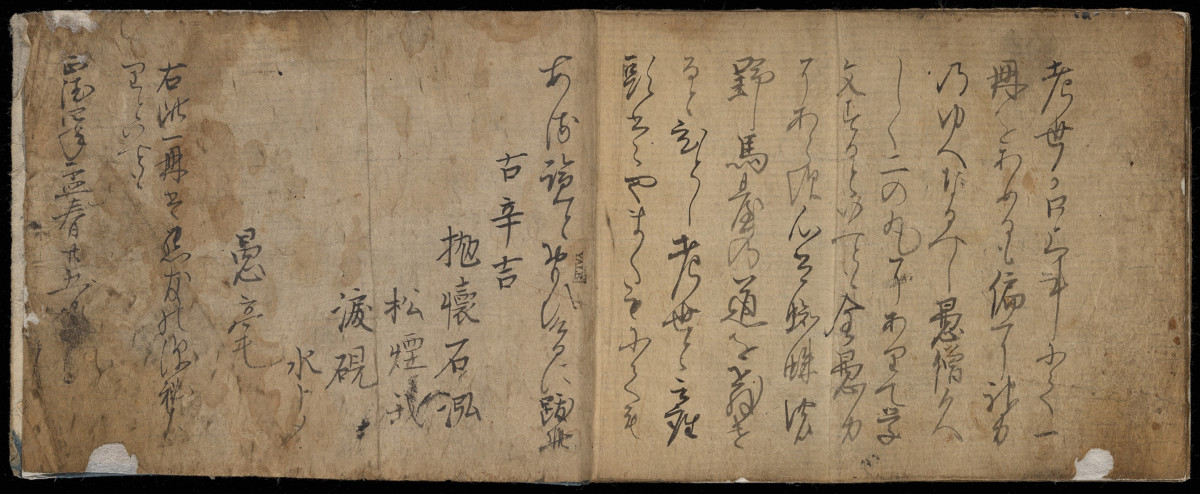

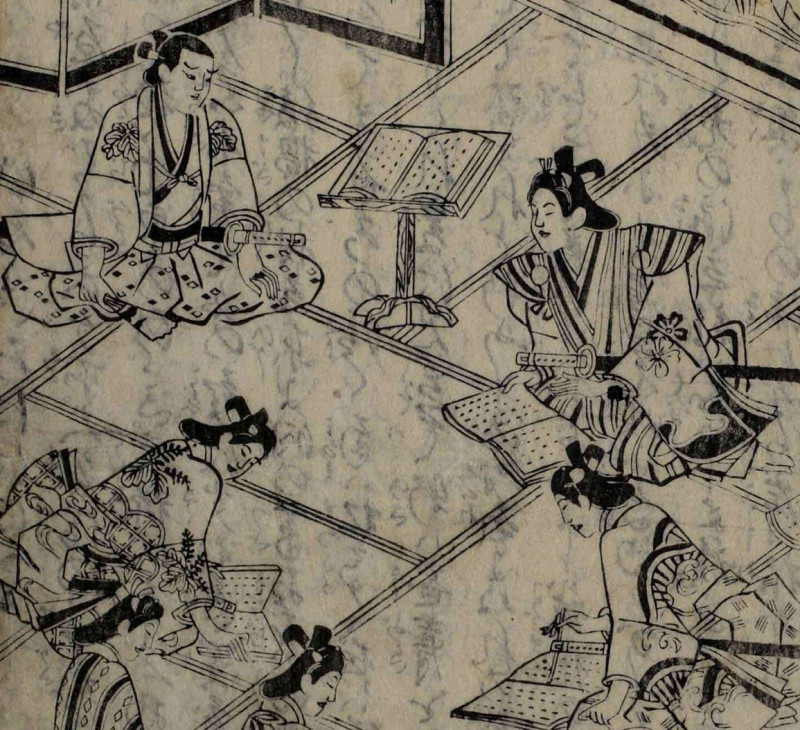

Our tale begins with an unassuming manuscript, bound in a simple black cover, lacking both a title slip and any indication of a title or the name of an author inside the book. Small in size, measuring merely 14.5 × 19.2 cm in a horizontal (yokohon 横本) format, the handwritten text sprawls across no more than twenty-two folios, the monotony of the black-ink brushwork interrupted at intervals by ten color illustrations, which closely follow the narrative inside. It is the designation "top secret" (shinpi 深秘) in the handwritten colophon on the final page, dated Shōtoku 4 (1714), that first alerts the modern reader to the "classified" and risqué nature of the contents.

Although now cataloged at Yale under the provisional title Shudō tsuya monogatari 衆道通夜物語 (A boys' love tale of all-night prayer), the manuscript would perhaps not have been known to contemporary readers by this name. It was also not the concept of shudō (love of youths) per se that would have made its content offensive and "secret" in early eighteenth-century Japan, where stories of male same-sex love circulated freely in the popular fiction and theater that emanated from the large urban centers.

So why then this rhetoric of secrecy and air of the forbidden surrounding this manuscript? To discover the reason, we need to delve into the world of its story.

Genta's Story

The narrative in the book revolves around a young samurai named Takenomata Genta 竹俣源太, a brilliant young man from a respected family who attracts the attention of a string of older lovers. His popularity leads to a host of baseless rumors initiated by jealous rivals, obsessive stalking by admirers, and the resentment of those who spend a handsome sum in their fruitless pursuit of him. A series of poor decisions sees Genta associating with worthless companions and alienating men of integrity, ultimately leading to his tragic demise at the age of sixteen, cut down in the street by a fellow samurai out of jealousy. Adding to the manuscript's sense of mystery, the story is set within the narrative frame of the bodhisattva Jizō appearing as a vision to personally transmit Genta's tale, thus effectively turning the deity into the omniscient (though partisan) narrative voice for the events that unfold.

The story thus has all the trappings of a riveting read: scandal, intrigue, betrayal, deep-seated jealousy, and declarations of endless love culminating in a violent murder, while accompanied by a generous smattering of racy allusions. It could easily have appeared as a typically melodramatic storyline in popular samurai fiction or graced the stage in any of the three major metropolises of Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka. Only this was not fiction. Takenomata Genta was a real-life samurai and his murder an actual event. It was in fact the veracity of this account and its socio-political implications that spelled danger and necessitated the manuscript's covert treatment of the subject matter (see Introduction Essay 2).

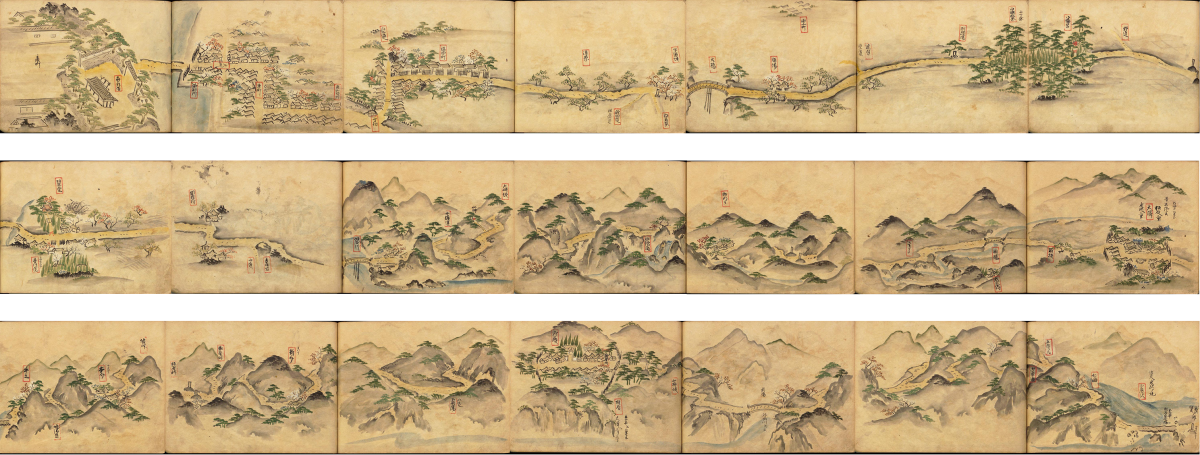

A Local Culture of Samurai Love

As such, the story takes us to a specific place at a specific time and features a set of characters with whom the writer may have been familiar. Penned at the beginning of the year Shōtoku 4, the manuscript captured the events in writing a mere couple of months after Genta's untimely demise in the tenth month of the preceding year (1713). The setting is Yonezawa domain in the northwestern province of Dewa (present-day Yamagata Prefecture), a fiefdom of roughly 150,000 koku ruled by the illustrious and once powerful Uesugi 上杉 family. The Uesugi had found themselves on the wrong side of history opposing the victorious future shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (1543–1616) at the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

With the Tokugawa family solidifying their position as the architects of the early modern landscape of power, the Uesugi were reduced to an eighth of their original income with nothing more than this northern fiefdom plagued by harsh climatic conditions, low agricultural productivity, and poor connections to national transportation routes. Yonezawa domain is known to modern historians for its highly successful economic reforms in the late eighteenth century, which revived domain finances through an emphasis on sericulture and silk reeling.

A far cry from the booming shogunal capital Edo, the story takes us into the close-knit community of mid-ranking warriors in this northern domain and its castle town of Yonezawa. The large cast of characters—at times perplexing to the contemporary reader with its profusion of names—suggests close familiarity with the local community and a certain expectation of the reader's insider interest in it, thus squarely rooting the manuscript within this social sphere. Most significantly perhaps, with its focus on the (alleged) amours surrounding the protagonist Genta, the manuscript conjures up a lively local samurai same-sex culture—or at least an imagined version of it.

Some far-flung locales on the Japanese archipelago, such as certain regions of Kyushu, were renowned as strongholds of warrior shudō, particularly in the nineteenth century following the Meiji Restoration.

To cite this page:

Koch, Angelika. "A Tragic Love Story in an Eighteenth-Century Manuscript." Blood, Tears, and Samurai Love: A Tragic Tale from Eighteenth-Century Japan. Japan Past & Present. 2024. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/blood-tears-and-samurai-love/introduction/a-tragic-love-story

For additional information on references and images, see our bibliography and image credits pages. Research for this page was generously funded by the Dutch Research Council.