True-Record Books: Scandals, Gossip, and Rumors in Early Modern Japanby Angelika Koch

The Truth is a Problem

But why precisely was the apparent veracity of this story problematic in early eighteenth-century Japan? Factuality and information regarding true events may appear unthreatening and even highly desirable qualities to the contemporary observer; yet in early modern Japan, the shogunal authorities were greatly preoccupied with controlling the flow of information available to the public and stemming the flood of certain unpalatable subjects—a problem that had become acute following the development of a commercial publishing industry in the early seventeenth century. To this purpose, legal pronouncements in the three metropolises of Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka targeted various categories of information from the 1650s onward, ranging from military chronicles to Christian texts, calendars, and erotica—and, most importantly for our purposes, any form of newsworthy, real-life events. In fact, anything "unconventional" and "bothersome to the public," as one prohibition issued in Edo in 1673 put it, was a potential target for legislators.

In practice, this meant that some topics were demarcated as off-limits for general publication in print. First and foremost, information about the shogunal government, its officials, regional lords (daimyo), and samurai retainers was not to be circulated without permission and was liable to potential punishment. Some of the earliest recorded cases of censorship in the seventeenth century, in fact, allegedly targeted a publication that had reprinted a letter by the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, and a somewhat revealing manuscript by a member of a shogunal inspection tour of the domains.

The Yale Manuscript's Illicit Story

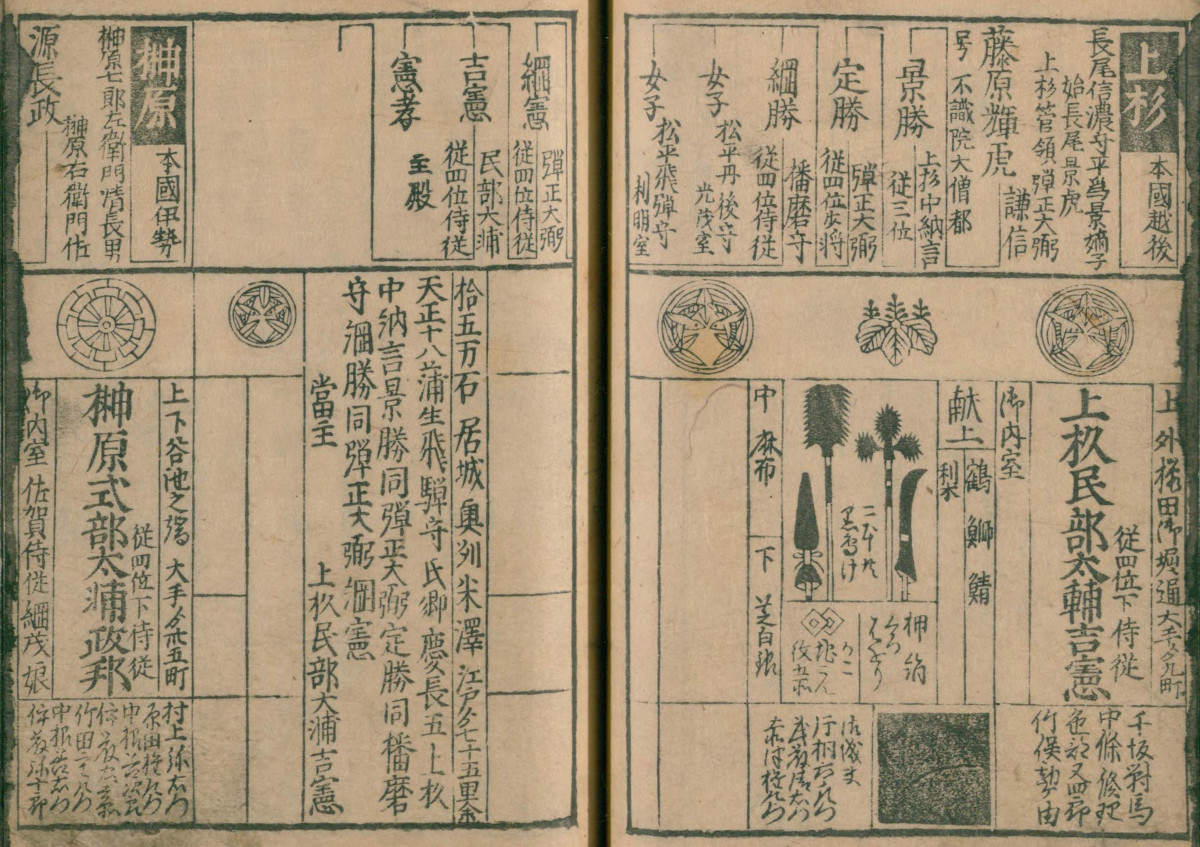

It is thus highly likely that our manuscript would have fallen foul of official regulations on a number of counts. Its content was at times sexually suggestive with male lovers spending the night together and falling asleep in each other's arms; and, more to the point, the protagonists in these amorous encounters were mid-ranking retainers of the daimyo of the Yonezawa domain, sometimes with their family lineages cited in the text. Genealogical detail was important for status-conscious warriors, but its use could be viewed as potentially offensive outside the context of officially sanctioned government and warrior household documents. One of the articles in the 1722 publishing regulations accordingly warned that "circulating information about a person's ancestors and lineage" was prohibited—though this implicitly referred primarily to daimyo and other high-ranking warrior households.

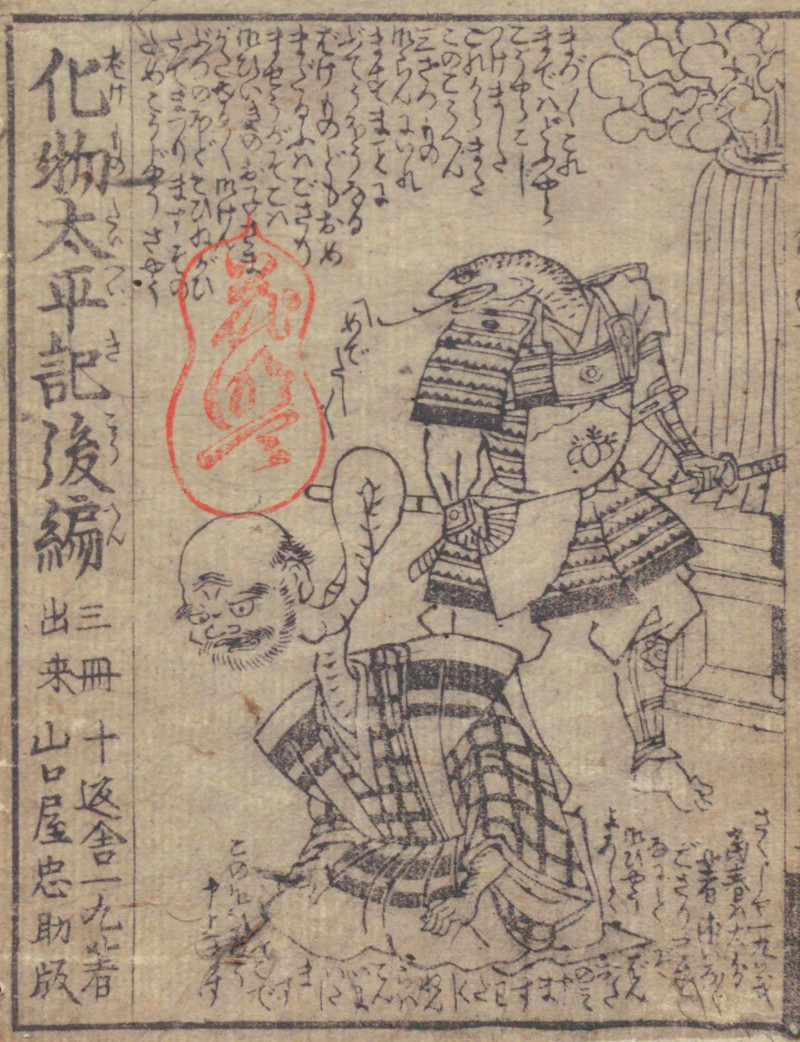

The manuscript's illustrations might likewise have caused offense, since they clearly identify the Yonezawa warriors by crests (kamon) on their clothing. Similar strategies for identifying characters in popular illustrated fiction such as "yellow-cover" (kibyōshi) books and woodblock prints would be met with bans and sanctions by the end of the eighteenth century.

Above and beyond this, however, it is clear that the manuscript as a whole was in blatant contravention of shogunal and domain exhortations to refrain from reporting scandalous events and other newsworthy gossip—for which the murder of a domain retainer in broad daylight in the streets of Yonezawa would have surely qualified. Although local Yonezawa practices of publication control remain at present unclear,

Banned News Means No News?

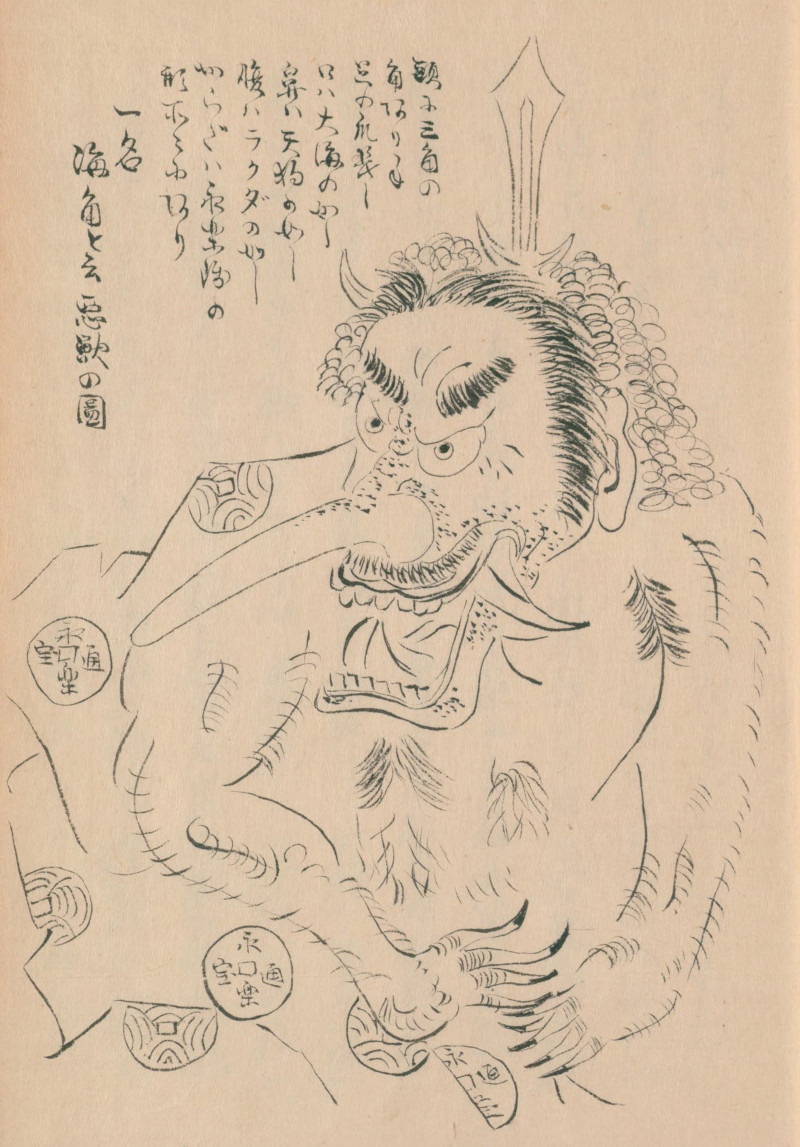

This is not to say that news and hearsay did not circulate in early modern Japan. The existence of our manuscript is already proof to the contrary, and reports on recent events spread in a variety of other forms. Yomiuri (lit. "reader-sellers") peddlers of cheaply produced broadsheets (kawaraban) hawked the streets of cities, reciting juicy titbits from the mishmash of notable current events contained in their ephemeral publications. These ranged from the Osaka military campaigns (1614–1615), revenge killings, and love suicides to fires and earthquakes, sightings of mermaids and monsters, impromptu sex changes, children born with two heads, the display of exotic animals such as elephants and camels, shogunal hunting trips, and the threatening arrival of Perry's black ships (1853–54) in the nineteenth century.

Edo News Gallery

"Sensation, sensation! Everyone is talking about it!"

Browse the latest Edo news below.

News, Edo-style

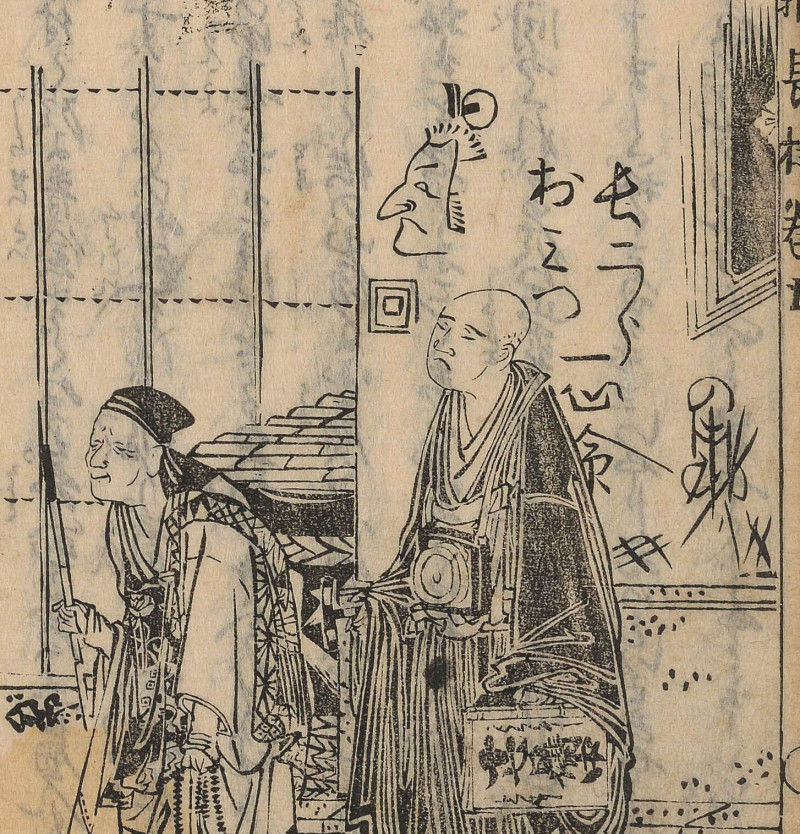

Storytellers (kōshakushi) performing on street corners, in makeshift shelters, and private houses likewise turned current events and street gossip into engaging narratives for the masses.

Kabuki and puppet theater also dramatized vendettas, scandals, and love suicides only weeks after the actual events had created a stir, thinly veiling their topicality with historical settings and slight alterations of protagonists' names. In the streets, graffiti (rakusho) satirizing current goings-on in verse, short prose, and caricatures was scrawled on buildings and appeared in flyers affixed to doors and walls or left for people to pick up.

Diarists of all strata got in on the act and assiduously recorded any notable talk of the town, whether it be mysterious footprints that had appeared on the shogunal castle ceiling, an ominous comet, a cherry tree miraculously sprouting a crop of clams, or the sighting of a demonic nocturnal bird (or perhaps just an owl?) at Edo Castle.

Shogun Murdered by His Wife?

At the time our manuscript appeared in 1714, the metropolises were thus awash with news, titillating talk, and rumors. Particularly following the sudden death in 1709 of Shogun Tsunayoshi, who had drawn much ire and ridicule from the populace for his radical edicts for the protection of animals as well as for his extravagance and favoritism, the rumor mill was abuzz, with people whispering that he had been murdered by his own wife or possibly the ghost of the first shogun, Ieyasu, to prevent a political catastrophe.

In fact, gossip and news surrounding him comprise one of the most prolific subjects in graffiti extant from the period.

Underground Manuscripts

In addition to these somewhat ephemeral forms of "news media" that proliferated despite the government's best efforts at containment, there was another powerful alternative that became a go-to for furtive subject matters in the early modern period manuscript. Strictly speaking, such texts were illegal and government regulations soon specifically outlawed handwritten texts on undesirable subjects. The catalog of banned books issued by the Kyoto booksellers' guild in the 1770s (Kinsho mokuroku, 1771) contains no fewer than 122 such manuscripts, which make up the bulk of texts on the list, and warns its members against handling such works.

True-Record Books—The Tabloids of Their Day

Early modern manuscripts were varied in their content and were by no means all illicit in nature, being the preferred medium for luxury custom-made items, private records and also texts of purely local interest. The strong local color of our shudō manuscript and perhaps its intended private use may have impacted the choice of format, but first and foremost it is the scandalous nature of its content that is likely to have deemed it unsuited for print. Even by the early eighteenth century there was a precedent for official punishment of authors of manuscripts that divulged intimate details of warrior houses—although such measures were often applied in a somewhat haphazard and case-by-case fashion.

Such works covered events of general interest that could not appear in print due to censorship, such as intrigue and power struggles in powerful warrior houses (o-ie sōdō), tragic revenge and passionate love stories, tales of gallant bandits and heroes of peasant uprisings, and sex scandals that rocked the highest echelons of society, such as the Enmeiin Affair (1803). Usually produced for public consumption rather than mere private enjoyment, some of these handwritten texts enjoyed a wide circulation as a staple of lending libraries, copied and recopied by readers, often accreting further details and embellishments along the way.

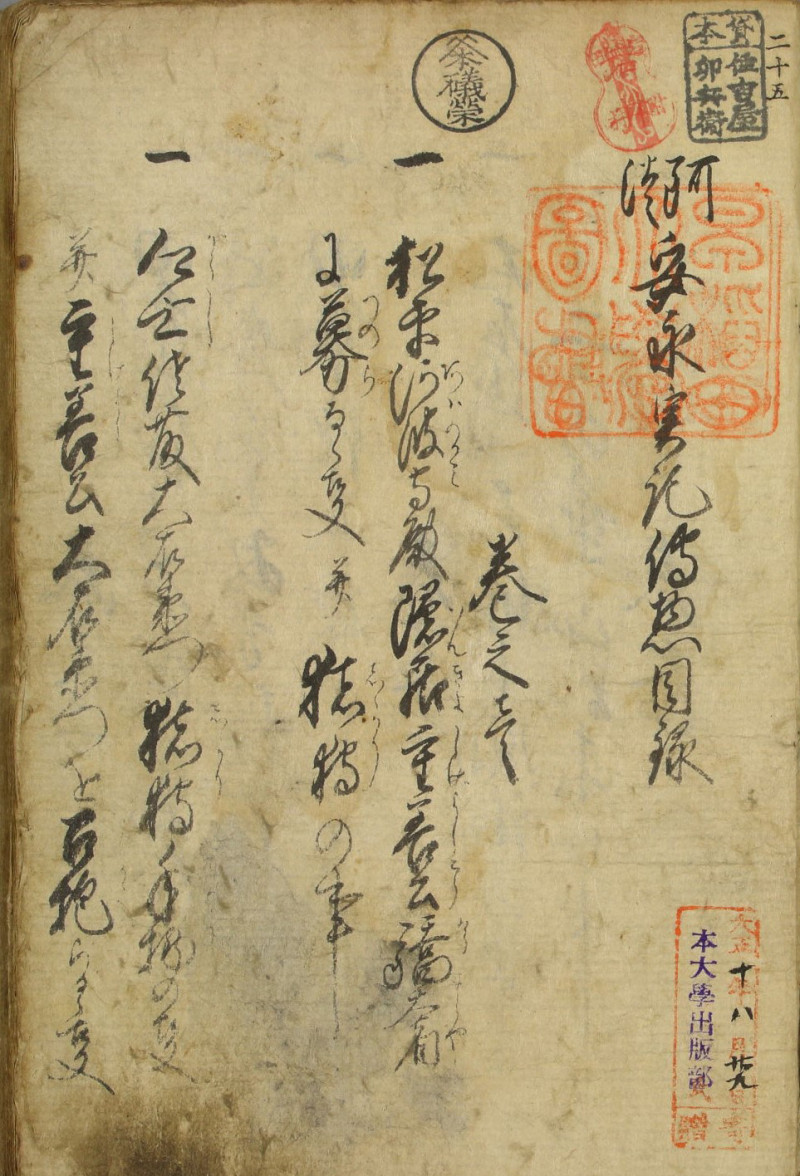

Our manuscript clearly bears all the hallmarks of such scandalous texts—love affairs, jealousy, revenge, murder, and the downfall of a (not so prominent) warrior house. Its author, as was typical of such "true-record" manuscripts, remains anonymous and its circulation obscure. The book displays no tell-tale signs of handling by a lending library and bears no owner seals that might provide clues to its provenance prior to its arrival at Yale's Beinecke Library in 2017. Its lack of a title further complicates the task of ascertaining the existence of other copies, as does the fact that "true-record" manuscripts frequently circulated under a number of different titles.

No matching work is listed in the most extensive, pioneering bibliography of premodern literature on "male love" (nanshoku) compiled by Iwata Jun'ichi or in the Union Catalogue Database of Premodern Japanese Texts.

To cite this page

Koch, Angelika. "True-Record Books: Scandals, Gossip, and Rumors in Early Modern Japan." Blood, Tears, and Samurai Love: A Tragic Tale from Eighteenth-Century Japan on Japan Past & Present. 2024. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/blood-tears-and-samurai-love/introduction/true-record-books

For additional information on references and images, see our bibliography and image credits pages. Research for this page was generously funded by the Dutch Research Council.