Hidden Christians & Oral History: Settlers and the "Indigenous"

Save PDFLesson Plan: Settlers and the "Indigenous" [Interview 2: Urakami Sachiko]

Created by: Gwyn McClelland, University of New England; (assisted by Nobuko Sakatani and Satsuki Osaki, Gotō Islands)

Creation date: January 23, 2024

Keywords: Identity, Baptism, Kakure, Gender, Discrimination

Interview 2: Urakami Sachiko

Target Audience:

Undergraduate students, Graduate students

Duration:

1 hour, not including reading time

Learning Objectives:

Consider the interviewee's concept of self in this interview. For further reading on this topic, see Lynn Abram's excellent Chapter 3 in her book, Oral History Theory, listed in Further Resources section at the end.1 However, as Abrams writes, "anthropologists have long alerted us to the fact that the so-called "invention of the self" is a construct of Western modernity and thus unfamiliar in other cultures." In the hybridic cultures that Urakami has grown up in, how does she draw upon personal and meaningful memory, as well as public discourses?

Use a "gender lens" in examining this interview. Ueno Chizuko (Feminist theorist) has written (translation Beverley Yamamoto), "The construction of reality is a key issue in the study of women's history. How do we reconstruct what amounts to another reality for women, lying behind the official histories written by men, when the possibility of obtaining historical facts is completely absent?"2

1 Abrams, L. (2016). Oral History Theory (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315640761

2 Ueno, Chizuko, 1948-. (2003). Nationalism and gender / Chizuko Ueno ; translated by Beverley Yamamoto. Melbourne : Trans Pacific Press, 4. Ueno, Chizuko. ナショナリズムとジェンダー. Japan: 青土社, 1998.

Potential Courses to Include this Lesson in:

Oral History

History

Japanese Studies

Asian Studies

Religious Studies

Required Materials:

interview (including audio stream), and photographs

associated readings

teaching guide/lesson plan

Activity/Procedure:

In preparation for the class first listen to Interview 2, and study the transcripts, referring to the vocabulary list as useful. Discuss your impressions of the interview as a class. Then, read the background information in this teaching guide. In small groups, discuss the learning objectives. There are further questions for discussion at the end of this guide.

Background:

In the Gotō Islands, the "settlers" known sometimes as hirakimon and at others as itsuki were not the persecutors, but the persecuted, and the "Indigenous," sometimes referred to as jigemon, were those who lived there before the Hidden Christian migrants arrived after 1797. The Kirishitan arrived on the Gotō Islands due to persecutions that happened on the Japanese mainland, Kyushu, especially in the Omura coastal region of Sotome. The Lord of Omura announced that due to overpopulation in that region that the farmers could only have one son in their families. Any consequent sons born would require infanticide.

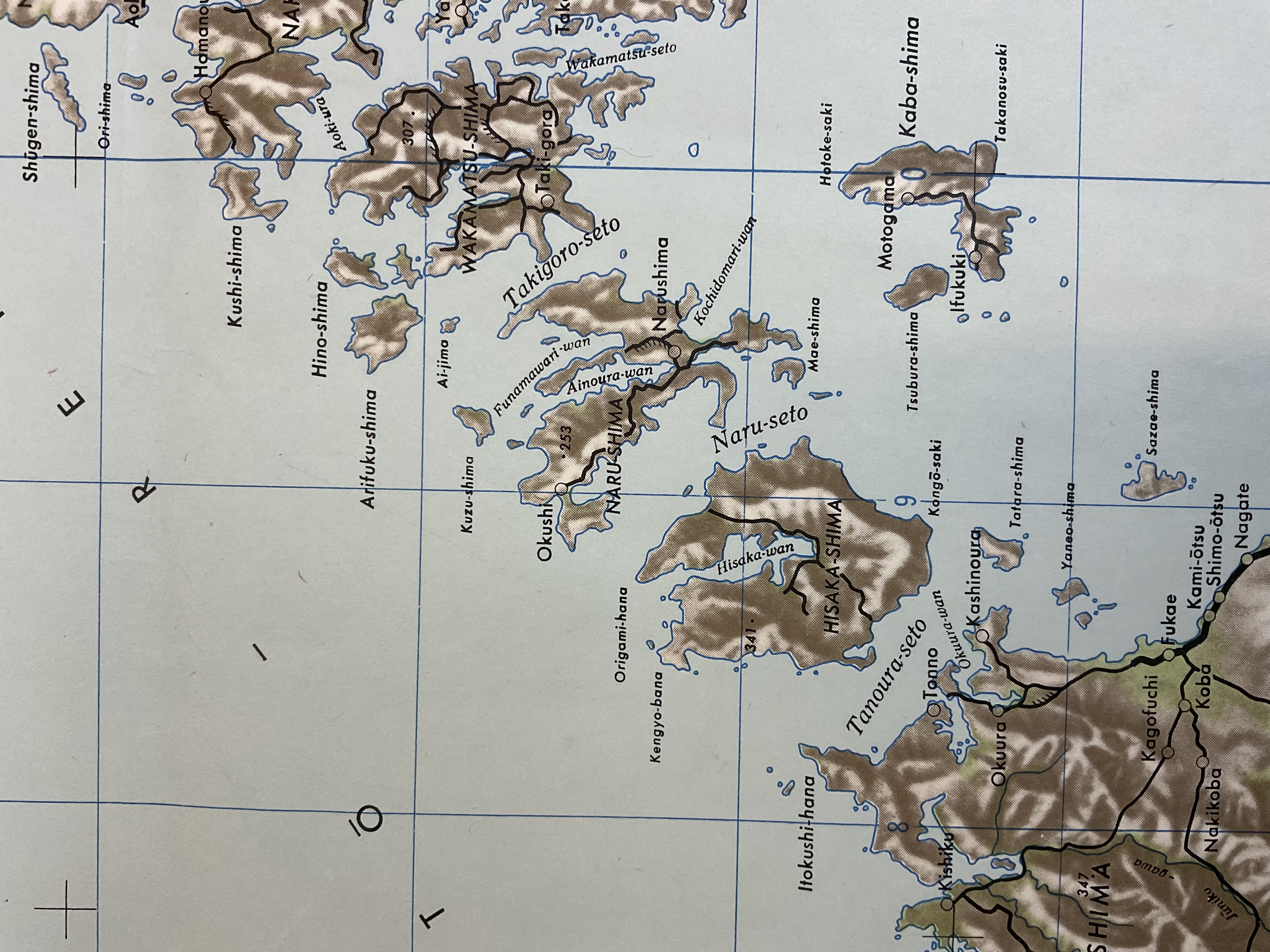

Today, many of those who are descended from the Kirishitan communities trace their own origins to Sotome. Still, there are some demographic differences on the islands today, especially in the percentage of modern day Catholics. On Naru Island, the focus of this interview, those descended from Hidden Christians that did not return to Catholicism, are said to number approximately 60% of the modern day population, alongside 10% who are Catholics. This compares to the 30% who are said to be Catholic today on the island south of Naru, Hisaka. In the northern region known as Kamigoto, there are similarly approximately 33% Catholic, while on Fukue Island, the number of Catholics is more like 12-15%. Naru Island is found immediately to the north of Hisaka Island and one of the Hidden Christian World Heritage sites is found within the island. It is Egami village, a small village on the Western side of the island, which includes a scenic church as well. However, the World Heritage site is not discussed in this interview.

The interviewee Urakami (Maiden name Hachiguchi) Sachiko lived in a small village named Yagami on Naru Island until she was 15 years old, and today lives on Fukue Island where she runs a small guesthouse. Fukue is the largest island in the Gotō group. This interview was carried out in the "Hidden Kirishitan Resource Center" managed by Kakimori Kazutoshi on Naru Island, across the harbor from Yagami. Because the interview was in the Resource Center, Kakimori (who I also interviewed separately) was also present and makes a few comments, especially toward the end of this excerpt of the interview. Otherwise, Urakami tells her own story. The audio has been edited to include the salient sections and has been edited to include five seconds of silence between each section.

The interviews carried out on Naru Island demonstrate a bias in the selection of the UNESCO Hidden Kirishitan World Heritage sites, not because of their connections to the Egami World Heritage village on Naru, but the opposite. When one examines the World Heritage listings, at least on the Gotō Islands, the chosen sites are skewed toward the modern Catholic sites, while Kakure sites are elided. Hisaka Island, Egami Village, Kashiragashima Village and Nozaki Village are all four communities that became predominantly Catholic post-1873. On Naru Island, though, the predominant grouping is of communities that did not become Catholic, and became known as Kakure Kirishitan instead while gradually reducing in numbers (see also Kakimori Interview). Some Hidden Christians who did not rejoin the Catholic Church and stayed hidden instead used newly built Shinto shrines in the late Nineteenth Century to hide their underground organizations. They continued various religious prayers practices from their forebears, that depending on the places, would be informed by the new and emerging Shinto state (during the Meiji and consequent eras) as well as the influences of Catholic communities now freely evident around them. Other Kakure communities were gradually subsumed by Buddhist and Shinto cultures, and came gradually to not participate in the Kakure practices any more.

In oral history, it is not uncommon for emotion to be expressed within the interview, and this one is no exception. In Section 4, Urakami tells me an emotional memory. I had asked whether there was anything else she heard about stories of her family. And Urakami told me about the story of her ancestors coming to settle this place on Naru Island.

Discussion Questions:

Some Hidden Christians did not return to Christianity post-1873. Why not?

What does Urakami Sachiko's journey tell you about the difficulties of returning to Christianity?

How was the transmission of Hidden Christian memory and practice gendered according to Urakami?

Urakami's brother, she says, told her about a "watchhouse" shack where the jigemon watched that the Kirishitan did not take shellfish, abalone etc. out of the sea, but only fish. The Kirishitan were highly susceptible to bullying especially in the Sempuku period, when Christianity was officially banned, but also after.

Can you extrapolate on why the bullying/discrimination may have continued beyond that time, after 1873?

Is there a story about your own family that you think would make you cry? What makes you emotional?

Evaluation:

After completing this lesson, students could write a short piece describing whether they agree with Lynn Abrams that "self" is a Western concept, and why from what you understood from Urakami Sachiko. Use a gender lens in your analysis.

Further Resources:

Abrams, Lynn (2016). Oral History Theory (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315640761.

Ueno, Chizuko, 1948-. (2003). Nationalism and gender ; translated by Beverley Yamamoto. Melbourne : Trans Pacific Press.

Reference Images for Use:

Growing sweet potato on steep slopes, on the Uome peninsula, Nakadori Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2023.

Growing sweet potato on steep slopes, on the Uome peninsula, Nakadori Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2023.

Nearby Akogi, where Kakimori Kazutoshi has worked to open up an old Kakure Kirishitan forest track, with the old stone walls alongside. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Nearby Akogi, where Kakimori Kazutoshi has worked to open up an old Kakure Kirishitan forest track, with the old stone walls alongside. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Naru Island and its surrounds, US Army Survey, 1:50,000, 1943. Courtesy of National Library of Australia, https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn7248195.

Naru Island and its surrounds, US Army Survey, 1:50,000, 1943. Courtesy of National Library of Australia, https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn7248195.

Credits/Acknowledgements:

Credit to Urakami Sachiko for the interview, and to Kakimori Kazutoshi for the venue for the interview. Also, thanks to Ryo Sasaki (Fukuoka), and Akira Nishimura (University of Tokyo) for their support in this project.