Tea Diariesby Morgan Pitelka

Chanoyu has endured in Japan as an influential social practice, as a technology for preserving and passing down material and visual culture, and as a primary component of the notion of "tradition" in part because it is also a textual practice. The core components of chanoyu in fact emerged alongside the writing of a corpus of texts, collectively known as tea diaries, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. This period was the first stage in the construction and codification of chanoyu, as elite urban merchants and military leaders recorded their tea experiences and philosophies in these diaries. It is to these textual precedents that writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries referred in their writings on tea as a defining component of Japan's identity. There are several issues in particular that need to be interrogated in a consideration of these primary texts. What was the purpose of the production of tea diaries? What role did they serve in society? What do these texts reveal about the economic and political function played by the tea practitioner in sixteenth and seventeenth century Japan? What role did the writing of tea diaries and the collecting of such texts play in tea history? Below, I explore the canonical tea diaries of this period. When citing specific passages from these sources, I have attempted to choose passages that are available in English translation to highlight the use of these texts by scholars of Japan.

One of the defining features of chanoyu, both in this century and during the late medieval and early modern periods, has been the practice of collecting tea utensils and visual culture for the gathering space and tea ritual. Not only tea utensils were collected, but the canonical texts of the tea tradition as well. This has been both beneficial and problematic for the study of the role of tea in Japanese history. On the one hand, the quantity of extant tea documents is fairly high: in the late twentieth century, one Japanese scholar gathered roughly 120 diaries recording over fourteen thousand tea gatherings, many of them documents that were preserved and protected as objects in larger tea collections.

Another concern in research on primary tea sources is the problem of authenticity. As Edo period tea schools competed for students and social influence, the legitimation of lineages and the dissemination of teachings became a major concern for tea practitioners. Possession of the writings of a tea luminary legitimized the pedigree of a tea school. But many of the texts that putatively represent the teachings of these masters in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in fact are either copies made in later periods, or new writings produced under the false pretense that they were written in an earlier era. Generations of copying has produced documents that are filled with inconsistencies and mistakes. Furthermore, the legitimizing function of these tea documents surely encouraged those producing copies to insert praise for objects from their own collections or to insert language that would "authenticate" the practices of their own tea school.

It would appear, therefore, that these tea documents are not always reliable as historical evidence. Rather than reject these rare and valuable primary sources, however, we can interrogate them as records of what their authors wanted readers to think and to know, and question the role that this writing played in the lives of all early modern tea practitioners.

Matsuya kaiki 松屋会記

(1533–1650)

This document is the earliest extant tea diary of the sort that became common in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It is composed of records of tea gatherings attended by three generations of the Matsuya family of lacquerware merchants: Hisamasa 久政 (?–1598), Hisayoshi 久好 (?–1633), and Hisashige 久重 (1566–1652). Kumakura Isao has written that the Matsuya kaiki is an important historical source because it represents the documentation of the birth of rustic tea (wabicha) among elite, urban commoners (machishū) during the shift from medieval to early modern society. In cities like Kyoto, Sakai, Nara, and Hakata, urban commoners used tea gatherings as a space of community, debate, and decision making.

The basic form of the diaries was fairly standardized, following the simple structure of Matsuya Hisamasa's first entry.

The Matsuya kaiki also illustrates the mobility of this class of merchant tea practitioners, who traveled for trade and socializing alike. The tea gathering played a growing role in social, economic, and political exchange and communication; chanoyu was rarely a matter of just drinking a mildly stimulating beverage, but instead provided the context for a host of communal and individual interactions. Between 1542 and 1544, for example, Matsuya Hisamasa traveled from Nara to Sakai at least twice, attending sixteen different tea gatherings with different hosts.

Tennōjiya kaiki 天王寺屋会記

(1548–1590)

This document (a portion of which is also known as the Tsuda Sōgyū chanoyu nikki 津田宗及茶湯日記), chronicles the tea activities of three generations of the Tsuda household of Sakai: Tsuda Sōtatsu 津田宗達 (1504–1566) records tea gatherings attended and hosted for 1548–1566; his son Sōgyū (or Sōkyū 宗及, d. 1591) records gatherings attended for 1565–1585 and gatherings hosted for 1566–1587; and his grandson Sōbon 宗凡 (dates unknown) records gatherings attended in 1590.

It is the middle section written by Sōgyū, however, that is the richest of the three, detailing at length the tea gatherings of the late sixteenth century, a period of great expansion and popularization for chanoyu. The first section of the Matsuya kaiki, covering the early sixteenth century, has few entries, focusing primarily on gatherings that required a trip out of Nara: the first Matsuya entry is dated Tenbun 2 (1533), the second Tenbun 5 (1536), the third Tenbun 6 (1537), and the fourth Tenbun 8 (1539), totaling only four gatherings in six years.

Major historical events are mentioned throughout the Tennōjiya kaiki as well, such as the Sakai Miyoshi attack in 1569 on the forces of Ashikaga Yoshiaki 足利義昭 (1537–1597) and the first unifier Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (1534–1582) in Kyoto.

The relationship between Sōgyū and Nobunaga presents an interesting example. Although Sōgyū initially sided against Nobunaga in the warlord's struggle with Sakai and the Miyoshi clan, he eventually came to support (perhaps grudgingly) the Kyoto hegemon, as illustrated by his participation in a tea gathering with Nobunaga at Myōkakuji in 1573 and a private viewing of Nobunaga's most famous utensils in 1574.

This is not to deny that there was in fact a great deal of focus on the aesthetic qualities of objects within the confines of the tea gathering or that the development of aesthetic judgment was essential to fluency in the code of interaction. As mentioned above, this obsession with the acquisition of tea utensils (meibutsu in particular) was one of the defining characteristics of sixteenth and seventeenth century tea. One example in the Tennōjiya kaiki is Sōgyū's enthusiastic description of his purchase of the Shigaraki mizusashi (water jar) "Gen'ya's devil bucket." "I brought this mizusashi back from Kyoto, and this is its debut. The guests could not have known that I had done so, for I returned home on the eighth day of the third month, having received the Shigaraki on the fourth day of the third month through the agency of Kokuan."

The acquisition of this tea utensil is on one level the fulfillment of Sōgyū's aesthetic longing for this specific ceramic object produced in a well-known style. But the emphasis in the text is on the upcoming tea gathering, an opportunity for Sōgyū to display this object and thus project buying power, social status, and economic, as well as aesthetic, sensibility. Sōgyū's purchase and display of this coveted water jar reifies and objectifies his social and business capabilities, symbolizing his connections in the world of tea and his ability to navigate the routes of political and economic power that constitute its boundaries. The language of aesthetics in the Tennōjiya kaiki and similar diaries is certainly not irrelevant, but neither is it simple; rather, this language operates in a profoundly complex ideological context, reflecting a multitude of related political, economic, and social meanings.

Imai Sōkyū chanoyu kakinuki (or nukigaki)

今井宗久茶湯日記書抜

This two-volume document records the tea activities of Imai Sōkyū, though the extant version of the text was edited in the late nineteenth century.

The relationship between Sōkyū and Oda Nobunaga illustrates the varied roles tea practitioners played in late medieval society. Sōkyū acted as a sort of ambassador for Nobunaga, who wanted cooperation from Sakai, one of the economic centers of sixteenth century Japan, without the necessity of resorting to military force. Tea men such as Sōkyū were important contacts not only because of their business and tea connections, but because many were members of the governing council of Sakai.

We also see in Sōkyū's diary the gradual rise of another figure in the late sixteenth century world of tea, Sen no Rikyū (known in the documents of the time as Sōeki). Although Rikyū has become the central superstar of chanoyu history, during Nobunaga's reign Sōkyū was the most highly acclaimed tea master. Andrew Watsky has suggested that Sōkyū should in fact be viewed as a model for Rikyū, whose greatest successes came only after the assassination of Nobunaga and the rise of Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉 (1537–1598) to power in 1582.

By 1587, with Nobunaga dead five years and Hideyoshi's patronage of Rikyū firmly entrenched, Sōkyū remained an active, if peripheral, figure on the tea scene. He records his participation in Hideyoshi's "Grand Kitano Tea Gathering" (see below) during the tenth month in some detail, including his personal decoration of his assigned tea hut: Mokkei's painting Autumn Moon and the tea jar Shōka, once in the possession of the tea master Murata Shukō (or Jukō 村田珠光, d. 1502).

Sōtan nikki 宗湛日記

(selected entries, 1586–1613)

This document is the record of Kamiya Sōtan 神谷宗湛 (1551–1635), the sixth head of the Kamiya merchant house of Hakata, which made its fortune off of trade with Ming China. The diary describes tea events in Kyoto, Sakai, and Hakata, and contains many entries involving prominent political figures of the day. For example, after Hideyoshi defeated the Shimazu of Kyushu, he stayed for a month at Hakozaki Shrine in Chikuzen province and called upon the merchants of Hakata, including Sōtan, to pursue channoyu with him. Sōtan describes one of Rikyū's tea gatherings at the shrine: "three thick tatami mats; a thatched roof; green thatched walls; a new ubaguchi kettle; and a metal brazier."

This connection with Hideyoshi and Rikyū is a key feature of the diary. Sōtan was often a guest at Hideyoshi's "ostentatious" displays of wealth, such as a showing of his golden tea room in 1592

Nanpōroku (or Nanbōroku) 南方録

(also known as Kissa Nanpōroku 喫茶南方 )

The Nanpōroku is one of the most celebrated of tea documents, putatively a record of Sen no Rikyū's "Way of Tea" as written by one of his disciples, a Zen monk from Nanshūji temple in Sakai known as Nambo Sōkei 南坊宗啓 (dates unknown). This document was "discovered" around the centennial of Rikyū's death (a time of much renewed interest in Rikyū's teachings) by Tachibana Jitsuzan 立花実山 (1655-1708), a vassal of the Kuroda domain in northern Kyushu and a student of the Enshū school of tea.

The Nanpōroku is composed of seven sections: Oboegaki (statements by Rikyū on tea); Kai (tea gatherings hosted by Rikyū); Tana (usage of utensil stands and shelves); Shoin (displaying utensils in the shoin room); Daisu (usage of the formal utensil stand); Sumibiki (measurements governing utensils and tea procedure); and Metsugo (words and deeds of Rikyū recalled after his death).

Despite the extensive scholarly debate over the historicity of the Nanpōroku, the text has maintained a canonical position in the tea tradition for centuries. Not unrelated to the popular endurance of this document is the issue of how and why Sen no Rikyū was (and continues to be) situated at the center of the entire tea tradition, deified and mystified by scholars and practitioners alike. A full study of the layers of myth and memory that constitute the written history of Rikyū is beyond the scope of this paper, but the Nanpōroku does raise a number of obvious questions. How has the amorphous written form of the Nanpōroku, as a haphazard collection of "maxims, rules, anecdotes, historical data, and random jottings,"

Kitano ōchanoyu no ki 北野大茶湯之記

This document records one of the major cultural events of the sixteenth century, Hideyoshi's 1587 "Grand Kitano Tea Gathering." A number of versions exist, but the two presented in the Chadō koten zenshū seem to be most often cited and are considered by tea scholars to be fairly reliable.

The event will take place, weather permitting, in the forest at Kitano shrine in Kyoto for ten days, so that Hideyoshi's entire collection of famous tea utensils (meibutsu) can be displayed to all serious devotees of tea. All those serious about tea should attend, also samurai's attendants (wakatō), townspeople (chōnin), farmers (hyakushō), and those of lower station, bringing a kettle (kama), a well bucket (tsurube), and a drinking bowl (donbutsu or nomimono); those without powdered green tea (macha) can use rice and salt tea (kogashi) without causing offense. Two tatami (or two-mat huts) per person will be appropriate because of the location in the Kitano pine groves; those of the wabi persuasion can use rough mat-covers (tochitsuke) or rice-straw [bags?] (inabaki); participants should arrange themselves as convenient. The invitation is not limited to Japan, but extends to anyone interested in tea, even those in China (karakuni). So as to display [the meibutsu] even to those from distant lands (engoku no mono made), the event will extend for ten days. This event is put forth for wabi tea practitioners; therefore, any who do not attend will from then on be considered in offense even if they prepare rice and salt tea (kogashi), as will any who consort with them. Hideyoshi will personally prepare tea for all wabi practitioners in attendance, not only those from distant lands.

In the next section, the document describes famous objects (meibutsu) from Hideyoshi's collection that were used and displayed at the event, including treasures originally from the collections of the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa 足利義政 (1436–1490), and the tea masters Takeno Jōō and Murata Shukō; of course Hideyoshi's golden tea hut was the center of much attention as well.

The event, however, did not go as planned. Considerably more attention was focused on the eccentric rustic tea practitioners than on Hideyoshi's own collection of famous objects. Perhaps the physical strain of serving tea to so many proved unendurable as well.

Yamanoue no Sōji ki 山上宗二記

This document is a record of tea practice according to the Sakai merchant Yamanoue no Sōji 山上宗二 (1544–1590), a disciple of Rikyū for twenty years. It differs from the other documents examined in this essay in its content and form, focusing more directly on objects and personalities in the history and practice of tea than on events hosted or attended. A commonly cited version of the document is divided into three sections.

The Yamanoue no Sōji ki has been of great interest to scholars of tea history for the detail of its descriptions, the author's categorization of types of tea practitioners, and most particularly for its discussion of famous objects; the document in fact is sometimes known as the Chaki meibutsu shū 茶器名物集. A 1995 catalog by the Gotoh Museum, Yamanoue no Sōji ki, places photographs and information on extant objects described in the Yamanoue no Sōji ki next to the actual text, with cross-references to other diaries of the period. The catalog provides historical essays, biographies of the production of the utensils and the lineage of their owners, and an extensive examination of the original texts. This connection between the text and the objects is emphasized throughout.

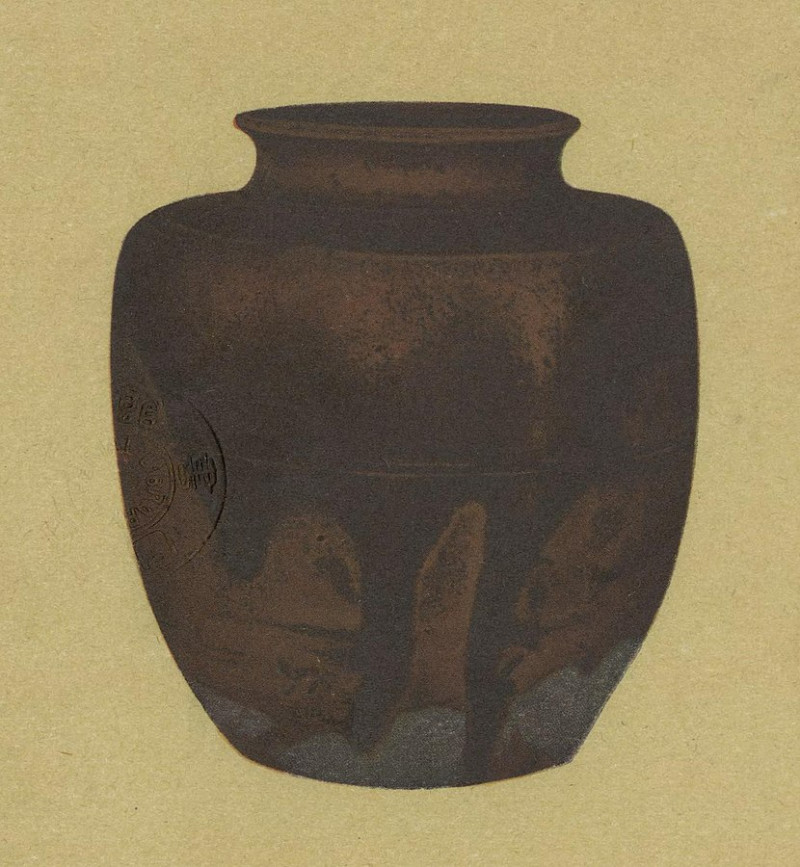

The catalog provides much detail for each individual famous object. One example is a tea leaf storage jar from the Southern Song-Yuan dynasty (13th–14th centuries). The jar is first listed in a chart that comprehensively describes the various objects from the Yamanoue no Sōji ki and their characteristics.

This genealogy of owners can be read as a biography of the "social life" of the pot, illustrating one of the key developments in this period of chanoyu's history: a major shift in the body of tea participants. The transfer of Shōka from Shukō, who had connections to the Ashikaga shogunate, to two entrepreneurial Sakai tea men represents a shift in the mid sixteenth century from institutional control and patronage of tea (i.e., warrior government and Buddhist) to increasingly autonomous participation by commoners, particularly wealthy urban merchants. The acquisition of the jar by three military figures in turn represents the increasing tea activities of the military class at the end of the sixteenth and into the seventeenth century. The most obvious example of this shift in the makeup of tea practitioners is Hideyoshi's total domination of the tea world in the late sixteenth century. We also see in the seventeenth century the primacy of warrior tea masters such as Hosokawa Sansai, Takayama Ukon, Shibayama Kemmotsu, Seta Kamon, Makimura Hyōbu, Oda Uraku, Maeda Toshinaga, Furuta Oribe, and Kobori Enshū, among others.

Finally, the jar is displayed in a full-page, detailed photograph. The accompanying catalog text gives quotations about the jar from the text of the Yamanoue no Sōjiki, and then lists quotes from other tea diaries of the period, including one reference from Matsuya Hisamasa's section of the Matsuya kaiki, and two from Tsuda Sōgyū's section of the Tennōjiya kaiki. This illustrates the intertextual, objectifying role of tea objects, which repeatedly appear as constants throughout the changing world of tea and its social, economic, and political components. As illustrated in the Yamanoue no Sōji ki, tea masters and tea practitioners flared and faded on the landscape of chanoyu, but many of the hoarded and coveted famous objects outlived even the words of their original owners to survive in museums and private collections today.

Conclusion

Several themes emerge from this brief consideration of a sampling of sixteenth and seventeenth century tea diaries. First, the practice of the connoisseurship and collection of tea utensils appears repeatedly in the sources. This was one of the marks of a chanoyusha, one of the three categories of tea practitioners that Yamanoue Sōji outlines in his writings. A chanoyusha was, by definition, 1) a connoisseur of tea utensils; 2) well versed in the art of tea; and 3) employed as a teacher of tea.

The collections that formed from such practices of connoisseurship represent a particular type of "conspicuous consumption."

Also key to these social repositionings was the strategy of display and the projection of authority. The display of objects, tea skills, and social connections in the course of tea gatherings allowed participants to publicly present their political, economic, and social identities in a controlled and limited setting. Changing definitions of the aesthetics of display signified the rise and fall of the fortunes of different members of the tea community. Tea schools formed and split under different tea masters who emphasized and created new patterns of display and aestheticism mined from their received tea lineages. These traditions were then codified in tea diaries of the sort examined above, creating the boundaries of knowledge about tea—in other words the history of tea itself.

This final theme of representation as the writing of history and tradition is the primary focus of this essay. Tea practitioners codified the stories, teachings, and gatherings of the tea masters, in the process producing the various histories of chanoyu. These histories were in turn re-presented by later generations of tea practitioners writing from within their own social contexts. It is this transformative nature of writing and representation that I have tried to emphasize, in that it illustrates the constantly diversifying character of tradition. The tea texts examined in this essay can be read against the subjective contexts of their original authors, against the larger historical context of the age of their production, against the reinterpretations of later eras, or against the various understandings of tea and tea tradition that dominate society today. All are critical elements of a holistic examination of the story of the role of tea in Japanese history, a story that is fragmented and intertextual rather than linear and monolithic.

To cite this page:

Pitelka, Morgan. "Tea Diaries." Teaching Tea: Culture, History, Practice, Art on Japan Past & Present. 2025. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/teaching-tea-culture-history-practice-art/resources/tea-diaries

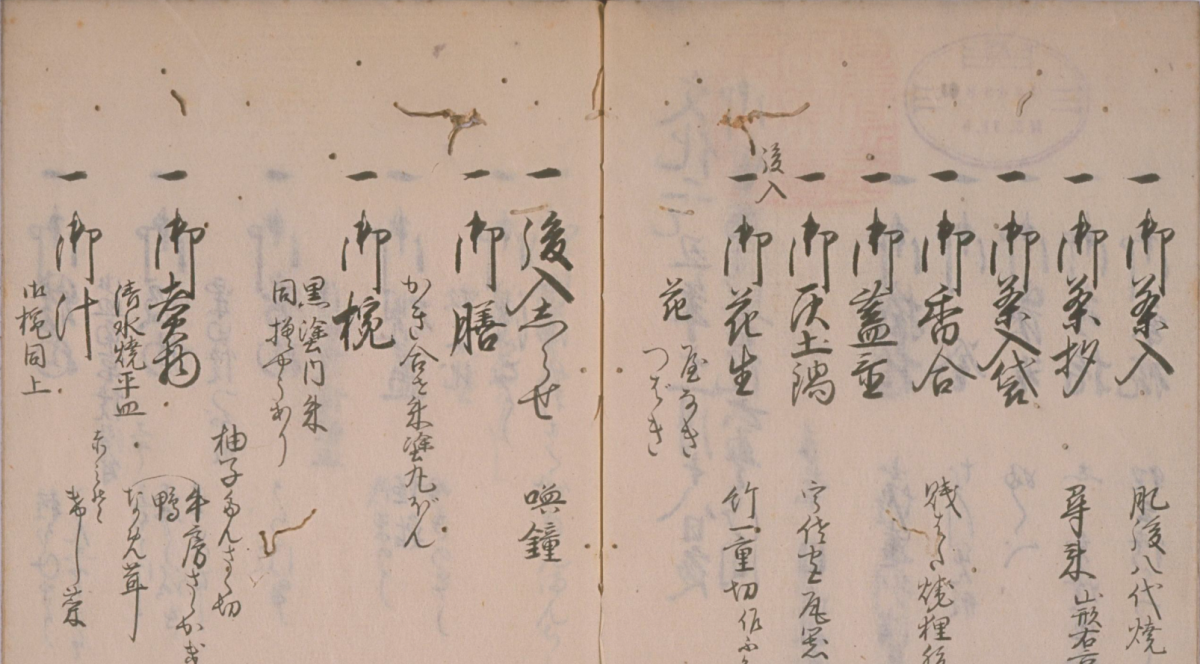

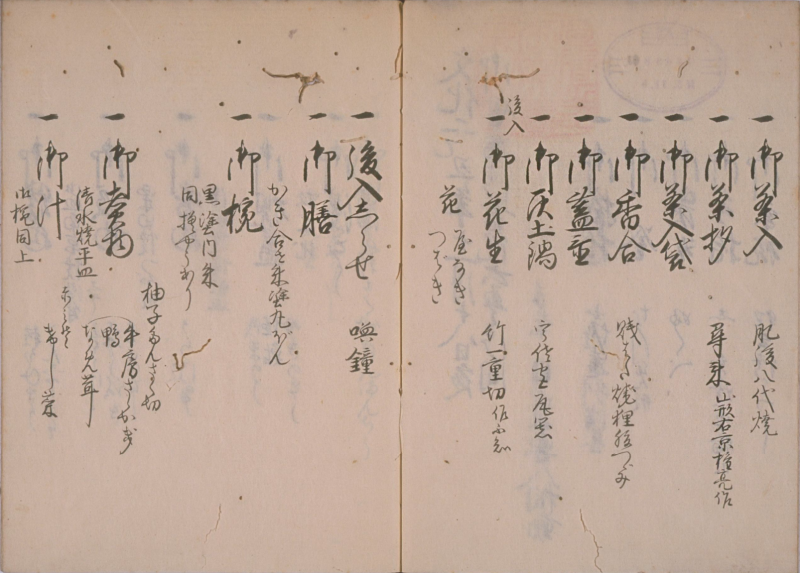

Header Image:

Sample excerpt of a tea diary from the Edo period. Tea Diary (Ochakaiki), Bunka 2 (1802).11.8. Kyoto University Library, RB00005912. https://rmda.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/item/rb00005912?page=3