Tea Outside of the Sen Schoolsby Melinda Landeck

The Proliferation of Schools in Early Modern Tea Praxis

Like most traditional arts in Japan, the formal instruction of tea has over time been diversified into numerous schools (ryūha) emerging from family lineages dedicated to the development and transmission of its rules of practice. In this way, tea was one locus of Japan's oft-cited iemoto seidō or "iemoto system," a system of family headship designed to oversee the preservation and transmission of cultural orthodoxy and artistic legitimacy within ritualized arts from one generation to the next.

Among these, the professionalized schools established by seventeenth-century descendants of the influential figure of the tea master Sen no Rikyū 千利休 (1522–1591) have tended to dominate tea discourse outside of Japan. The so-called "three Sen family schools" are known collectively as the sansenke: a group comprised of the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakōjisenke tea schools. A fourth affiliated school, the Edosenke-ryū, was founded in Edo (present-day Tokyo) by Kawakami Fuhaku 川上不白 (1719–1807), a disciple of the seventh-generation Omotesenke grand master but not a member of the Sen family line.

For many outside Japan, the Sen family schools constitute the most readily accessible face of contemporary tea practice and scholarship. Among these, two (Urasenke and Omotesenke) garner the lion's share of visibility in international tea circles and have assumed leading roles in the production and publication of foreign-language texts on tea, its history, guiding principles, and modern-day practice.

But the field of tea praxis in Japan is far more diverse than many people realize. Japanese history documents the existence of nearly thirty separate tea schools, each with its own founding figure, textual traditions, and prescribed etiquette, and roughly half of these survive in some form to the present day.

The Emergence of Warrior Tea

Many of these early schools emerged from warrior households whose members studied tea, including some that trace their origins to a group of seven men who studied directly under the tutelage of Sen no Rikyū himself. Sometimes referred to as the "seven sages of Rikyū" (Rikyū shichitetsu), this group was comprised of men who, like Rikyū himself, served the hegemon Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉 (1537–1598) and studied tea under Rikyū during the late sixteenth century. All seven were high-ranking warriors: Hosokawa Tadaoki 細川忠興 (also known as Sansai, 1563–1646), Furuta Oribe 古田織部 (1544–1615), Maeda Toshiie 前田利家 (1538–1599), Gamō Ujisato 蒲生氏郷 (1556–1595), Takayama Shigetomo 高山重友 (more commonly known as Ukon and sometimes as Nanbō, 1552?–1615), Makimura Masaharu 牧村政治 (also known as Hyōbu, 1545–1593), and Shibayama Munetsuna 芝山宗綱 (also known as Kenmotsu, dates unknown).

These men were among the earliest practitioners of and patrons for what tea historians describe as "warrior tea" (buke-cha), and several of them went on to found their own eponymous tea schools (e.g., Sansai-ryū and Oribe-ryū), which in turn also generated additional offshoot warrior schools from the cohorts of their own disciples. One such example is the Ueda Sōko-ryū, a Hiroshima-based tea school named for a warrior (Ueda Sōko 上田宗箇, 1563-1650) who studied under both Rikyū and Furuta Oribe before founding his own lineage, which has continued to the present day.

Representative examples of schools outside of the Sen lineage include the following (hyperlinks have been included for schools with an active online presence):

Chinshin-ryū (鎮信流), founded by Matsura Chinshin 松浦鎮信 (1622–1703) and localized in present-day Nagasaki Prefecture. This school is considered an offshoot of the Sekishū school listed below.

Enshū-ryū (遠州流), founded by warlord tea master Kobori Enshū 小堀遠州 (1579–1647). Enshū-ryū is one of two schools that claim Kobori Enshū as founder. See also Kobori-Enshū-ryū below.

Hayami-ryū (速水流), founded by Hayami Sōtatsu 速水宗達 (1727–1809), a student of the eighth-generation Urasenke grand master Yūgensai 又玄斎 who was granted permission to establish a school of his own in Okayama.

Hosokawasansai-ryū (細川三斎流), founded by Hosokawa Tadaoki (tea name, Sansai), who was one of Sen no Rikyū’s original "seven sages." An offshoot of this school was the later Oie-ryū (御家流), which was founded by the warrior Andō Nobutomo 安藤信友 (1671–1732).

Kobori Enshū-ryū (小堀遠州流), a second tea school claiming to preserve the legacy of warlord tea master Kobori Enshū as its founder. Their lineage emanates from Enshū's brother Kobori Masayuki 小堀正行 (1583–1615). See also Enshū-ryū above.

Nanbō-ryū (南坊流), a school that claims Nanbō Sōkei 南坊宗啓, the putative writer of the Nanpō-roku 南方録, as a founder. The lineage has become decentralized and non-hereditary with various teachers representing the school by location.

Oribe-ryū (織部流), a school that, like the Hosokawa Sansai-ryū, was founded by another one of Rikyū's "seven sages," the warrior Furuta Oribe.

Sekishū-ryū (石州流), a school developed by the warlord Katagiri Sadamasa 片桐貞昌 (also known as Katagiri Sekishū, 1605–1673), lord to Koizumi Domain. The Sekishū school was later divided into multiple branch schools, and during the Tokugawa era (1603–1868) it exercised significant influence over chanoyu practice in various regions of Japan.

Sōhen-ryū (宗偏流), founded by Yamada Sōhen 山田宗徧 (1627–1708), one of the four primary disciples of Sen no Rikyū's grandson, Sen no Sōtan 千宗旦 (1578–1658). See also Yōken-ryū below.

Sōwa-ryū (宗和流), founded by warrior Kanamori Sōwa 金森宗和 (also known as Shigechika, 1584–1656).

Ueda Sōko-ryū (上田宗箇流), named for warrior Ueda Sōko, who studied under both Sen no Rikyū and Furuta Oribe before founding his own school.

Yabunouchi-ryū (薮内流), founded by Yabunouchi Kenchū 藪内剣仲 (also known as Jōchi, 1536–1627), a contemporary of Sen no Rikyū who also learned chanoyu from the early tea master Takeno Jō'ō. Like the three main Sen family schools, Yabunouchi-ryū is primarily based in Kyoto.

Yōken-ryū (庸軒流), founded by Fujimura Yōken 藤村庸軒 (1613–1699) one of the four primary disciples of Sen no Rikyū's grandson Sen no Sōtan. See also Sōhen-ryū above.

Among the sects of tea currently active within Japan, perhaps only the two Enshū schools can compare to Omotesenke and Urasenke in terms of influence on a national, rather than regional, scale. Named for the warlord tea master Kobori Enshū, who himself was one of Oribe's disciples, the modern Enshū school is split into two separate Tokyo-based branches, each one with their distinct iemoto lineage: Kobori Enshū-ryū and Enshū-ryū. Unlike Omotesenke and Urasenke, however, the Enshū school as a whole has largely proven unable to expand their reach outside of Japan. This is not to suggest that attempts to broaden the appeal of the Enshu tradition have not been made: to wit, a 2013 documentary film entitled My Dad is the Iemoto: The World of Kirei-Sabi (Chichi wa iemoto: Enshū-ryū chadō kirei-sabi no sekai 父は家元 遠州流茶道 綺麗さびの世界) traces the day-to-day private and public-facing activities of the current Enshū-ryū grand master, Kobori Munemitsu, the thirteenth-generation family head, as narrated through the perspective of his daughter. But the film was never subtitled in English and remains unreleased to international audiences, in stark contrast to the multiple feature films and other media concerning the life and art of Sen no Rikyū that have been subtitled in English and promoted abroad in recent decades.

Although the cultural legacies of warrior tea masters such as Furuta Oribe and Kobori Enshū continue to be recognized as sufficiently impactful to merit equal billing with Sen no Rikyū in recently-organized major exhibitions of historical tea artifacts in Japan, the fact remains that outside Japan, Sen no Rikyū and the tea schools which bear his family name are far more widely known.

The Power of Taste (konomi)

The proliferation of diverse tea schools among warrior and non-warrior groups during the early modern period speaks to the growing appeal of tea among multiple social classes. One driving force behind the founding of new schools as the art has continued to grow in popularity was the creation of textual records expressing the approach of newly emerging tea masters to the practice, including explications of their tastes in the selection and arrangement of the many objects necessary to it. This focus on the individual tastes (konomi) of tea masters, recorded in artistic treatises, tea diaries, and other subgenres of tea texts became another key point of distinction between various schools and the modes of practice each expounded.

As one example of how various tea schools used "taste" as a metric for artistic difference, consider how the warrior tea master Kobori Enshū consulted with fellow warrior tea practitioners to evaluate the quality of ceramics produced at kilns they patronized and also collaborated extensively with potters at Japanese kilns to produce teawares made to his own particular specifications. These patterns of appraisal and selection formed the basis for Enshū's textual documentation of his aesthetic assessments of the merits of objects such as tea containers. In this fashion, Enshū and many other founders of tea schools contributed to a body of literature which listed and described the merits and cultural biographies of "renowned objects" (meibutsu)—historically or artistically significant tea utensils with which tea practitioners were expected to be culturally conversant regardless of the school in which they studied. Thus, both the notion of a school’s defining tastes (konomi) and the celebrated tea objects (meibutsu) in its possession contributed to the numbers of alternate schools of tea praxis that emerged from the seventeenth century onward.

Promoting Tea Outside of Japan

In stark contrast to the typically regionalized reach of many smaller tea schools, the activities of the Sen family schools, and of Urasenke in particular, have consistently reached international audiences. Urasenke, for instance, has established branch offices around the world including North America (several branches in the continental United States and Canada), In Central/South America (Brazil and Mexico), Europe (France, Germany, and Italy), Oceania (Australia), and Asia (Korea and the People's Republic of China). Moreover, the publishing arm of the school, Tankosha Publishing, has produced a significant number of English-language resources for the formal study of tea, and much of the English-language scholarship on tea and tea history has been published through academic presses at the University of Hawai'i and other schools with whom the Urasenke school has maintained longstanding ties.

As noted previously, the three schools directly connected to the Sen family tend to dominate the field of global chanoyu training and publishing outside of Japan and in languages other than Japanese. The Urasenke school, for instance, has welcomed foreign visitors to its Kyoto tearooms both as guests and as students from at least the turn of the twentieth century onward. Active international outreach and tea education was largely initiated by former family head Sen Genshitsu (Hounsai), who traveled abroad in the postwar period—along the way realizing the broad appeal and cultural adaptability of the art to non-Japanese practitioners and contexts—and establishing the first Urasenke chapter outside of Japan in Hawai'i in 1951. He wrote of this experience that "In the Way of Tea . . . there is no difference between whether one is Japanese or not; the only difference that exists in tea is whether one is a chajin [tea practitioner] or not."

Sen Genshitsu spearheaded many efforts to globalize the appreciation of tea practice and spread his message of "peace through a bowl of tea" during the postwar era. Since 2012 he has served as a Goodwill Ambassador for UNESCO, among other roles.

Variations of taste between schools have continued to function as a compelling facet of tea culture to the present time. Recent exhibitions of tea objects in Japan, including Chanoyu Aesthetics: Rikyū, Oribe and Enshū's Tea Utensils (Chanoyu no bigaku: Rikyu, Oribe, Enshū no chadōgu), which was hosted at Tokyo's Mitsui Memorial Museum in spring 2024, illustrate the extent to which tea remains a unified artistic field even while the particularities of different schools are recognized and celebrated.

References

Gorham, Hazel H. Japanese and Oriental Ceramics. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1971.

Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History, and Practice. Edited by Morgan Pitelka. London: Routledge, 2003.

Plutschow, Herbert. The Grand Tea Master: A Biography of Hounsei Soshitsu Sen XV. Trumbull, CT: Weatherhill, 2001.

"Schools of Japanese tea." Wikipedia. Last modified November 23, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schools_of_Japanese_tea.

Tea in Japan: Essays on the History of Chanoyu. Edited by Paul Varley and Kumakura Isao. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i, 1989.

To cite this page:

Landeck, Melinda. "Tea Outside of the Sen Schools." Teaching Tea: Culture, History, Practice, Art on Japan Past & Present. 2025. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/teaching-tea-culture-history-practice-art/resources/tea-outside-of-the-sen-schools

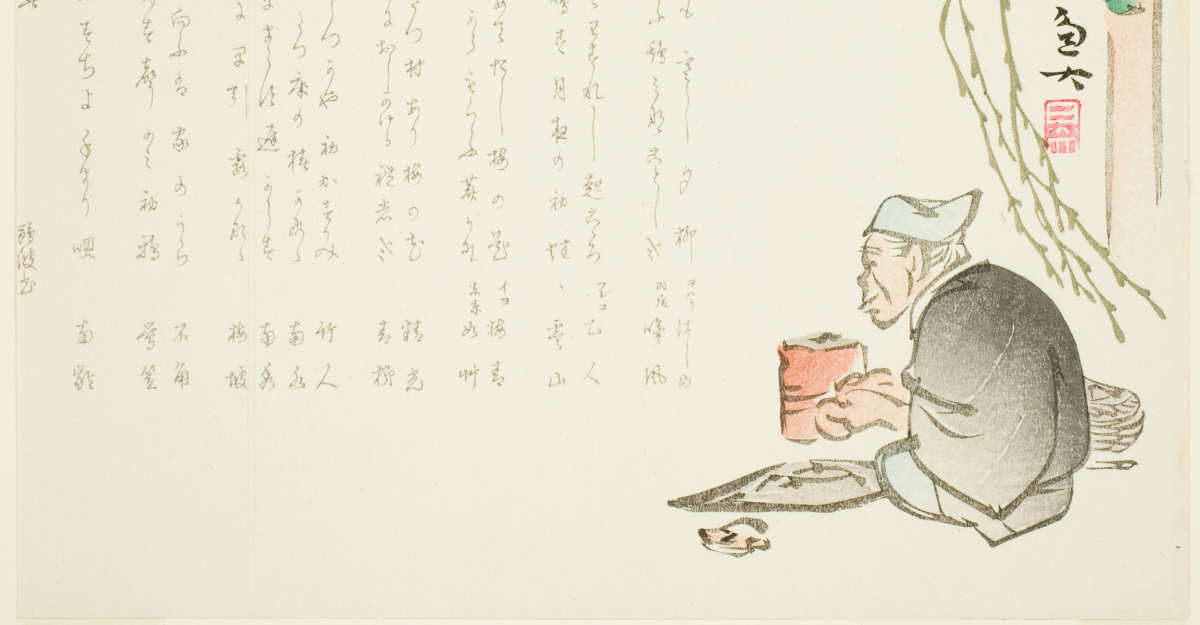

Header image:

Sato Gyodai. Elderly Tea Master, c. 1875. Color woodblock print, surimono; 24.2 × 19 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, 1984.1364.