Hidden Christians & Oral History: The Narrow Jail (Rōya no Sako) Incident of 1868

Save PDFLesson Plan: The Narrow Jail (Rōya no Sako) Incident of 1868 [Interview 1: Miyamoto Jitsuo and Fujie]

Created by: Gwyn McClelland, University of New England; (assisted by Nobuko Sakatani and Satsuki Osaki, Gotō Islands).

Creation date: January 23, 2024

Keywords: Trauma, Torture, Martyrdom, Samurai, Memory

Interview 1: Miyamoto Jitsuo and Fujie

Target Audience:

Undergraduate students, Graduate students

Duration:

1 hour, not including reading time

Learning Objectives:

Identify some elements of "what makes oral history different." Students should read Alessandro Portelli's classic essay originally published in 1979 of the same title.1 Portelli lists orality, narrative form, subjectivity, the "different credibility" of memory and the relationship between interviewer and interviewee, suggesting these compose strengths rather than weaknesses.

Consider "landscape" and memory: Is there evidence of the influence of environment on memory and history in this interview excerpt?

Discuss from your study of these interviews how you would go about studying a community through oral history. To take this further, students could read Linda Shope's essay entitled "Oral History and the Study of Communities," Chapter 21 of the Perks and Thomson, Oral History Reader Edition 2, listed in the resources.

1 Alessandro Portelli, "What Makes Oral History Different," in Oral History, Oral Culture, and Italian Americans, ed. Luisa Del Giudice, Italian and Italian American Studies (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2009), 21–30, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230101395_2.

Potential Courses to Include this Lesson in:

Oral History

History

Japanese Studies

Asian Studies

Religious Studies

Required Materials:

interview including audio stream, and photographs

associated readings

teaching guide/lesson plan

Activity/Procedure:

In preparation for the class first listen to Interview 1, and study the transcripts, referring to the vocabulary list as useful. Discuss your impressions of the interview as a class. Then, read the background information in this teaching guide. In small groups, discuss the learning objectives. There are further questions for discussion at the end of this guide.

Background:

What happened at Rōya no Sako?

Rōya no Sako means literally the narrow jail. This was a small jail on Hisaka Island that more than two hundred Kirishitan villagers, men, women and children, were forced into by the local lord, or daikan in 1868, while many endured torture, to encourage them to apostatize from Christianity. According to the local museum, forty-two victims died, including three after they were released due to injuries from torture, sickness, exposure, or starvation. Married Catholic couple, Fujie and Jitsuo Miyamoto, today parishioners of Hamawaki Church, on Hisaka Island, discuss in this interview the Rōya no Sako incident where islanders including Fujie's ancestors were tortured. This religious persecution happened at almost exactly the time that the government changed from the Shogun to the Meiji Emperor in what is called in Japanese 明治元年 Meiji Gannen (first year of the Meiji era) in the Western calendar, 1868.

When project leader Gwyn McClelland asked team member, and Hisaka Island resident and "pilgrim's guide," Sakatani Nobuko, about this incident, she said:

As a guide on Hisaka Island, at first, guiding people was intensely troubling, or "troubling"?, I wondered how I could explain well about Rōya no Sako. Yes, that Rōya no Sako: when I look at the writing about it by priests, it is really as if it was not about a human thing, or as if it is not a thing that could have been done by people.

Truly, there are so many horrible things written about it, and you could say my chest hurts… explaining…[to my clients] […] But you have to explain it as it happened […] Explaining is painful […] They were treated horribly but, well, from the first, there were [social] associations. It is written that there were kind Buddhists that meant [others] survived. […] Yes, and that lifts my heart a little […]

In 2018 UNESCO included Hisaka Island in its entirety as a Hidden Christian Cultural World Heritage site. While sparsely populated, with only approximately 250 people today, Hisaka Island is today said to have the highest proportion of Catholic believers of the Gotō Islands, at up to between 25 and 38%.2

2 Yōko Gotō, Gotō Rettō: Ritō wo tanoshimu (Tatsumi Shuppan, 2022), while 300 people are registered as living on the island, and Gotō suggests there are in actuality around 200 (as some move among the islands for work or other reasons) In 2021, there were 76 people in the Hamawaki Parish, the remaining Catholic church on the island. While it is difficult to assess the numbers, there would therefore be at maximum 38%, or at minimum perhaps 25% Catholics on this island. Sakatani Nobuko suggests there are actually only around 50 people at the parish now, so it is probable the proportion is reducing to the 25% or even lower.

Martyrdom in Catholicism

John Whittier Treat has stated that Christian tradition in Nagasaki emerged from memory of martyrdom and suffering. [3] There is more to consider about tropes of child martyrdom in Japan and Asia. For example, a Catholic hibakusha named Ozaki Tomei in Nagasaki named himself after a child martyr. [4] Of course children (and many others) do not seek to be martyrs. Those who died in the Hisaka Island martyrdom included 9, 6, 5, 3, and 1 year-olds. It reminds Gwyn McClelland in this project of the interviewing of Catholic survivors about the atomic bombing between 2008 and 2016. A disproportionate number of victims in Nagasaki when the US Army dropped the atomic bomb were women and children. [5] See also Nakamura Mitsuru's interview (found in this project). Nakamura reflected on how his great-grandmother talked about her grieving, after the death of her three young daughter's all at this place, Rōya no Sako.

At the end of this interview extract, Miyamoto Fujie states that her ancestor who died in the Rōya no Sako incident was named Masagorō. In 2022, Gwyn McClelland visited the martyrdom site where Masagorō's remains are interned, known as Rōya no Sako 牢屋の窄, with Sakatani Nobuko, long-time resident of the island. Historian Kataoka Yakichi writes that there is power that martyrdom places like this one exert (junkyochi) – including the remains of churches or places where people were killed. The Rōya no Sako witnesses to that time before the churches returned to Nagasaki. Kataoka suggests by this that the witness to the peoples' suffering, therefore, is the land of Hisaka, the trees, hills and rocks plus the harbor, where the daikan carried out tortures on the people.

[3] John Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb. Also see Yuki Miyamoto, Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility after Hiroshima (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), 139.

[4] Gwyn McClelland, "Love Saves from Isolation": Ozaki Tomei and His Journey from Nagasaki to Auschwitz and Back. in Chad Diehl (Ed.) Shadows of Nagasaki: Trauma, Religion and Memory after the Atomic Bombing, 2023, Fordham University Press, 112-130.

[5] Gwyn McClelland, Dangerous Memory in Nagasaki : Prayers, Protests and Catholic Survivor Narratives (Routledge, 2019), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429266003.

Afterword:

As Gwyn McClelland prepared to leave the island in 2023, he was driven to the ferry by an acquaintance who expressed an interest in what he had been researching. The driver then revealed that on his mother's side, his family had been a part of what happened at Rōya no Sako. In his case, his ancestors had been a samurai family, including officials who had arrested the Kirishitan and put them in the jail. The driver said that the Catholics tended to lie about it: there was no way that more than two hundred people could have fit in that space, he said. Another controversy was exactly where the representative of the Fukue Lord actually lived. While the Catholics suggest it was where the community house has been built today, others say that it was not necessarily there.

There is still a gap of understanding between different groups on the island - and a tendency to question the Hidden Christian history here.

Discussion Questions:

What do silences express within this interview?

What about laughing? What could these signify? Are there examples that demonstrate different meanings? Examine the context when someone laughs.

How has the community commemorated, and historicized the event of Rōya no Sako, according to Fujie and Jitsuo?

When did the community do research to add to what they knew?

What exactly can we know today about the historical record - what is most likely, and more than that, what does it mean now? What exactly was the number of people inside the jail? What else might we want to know about this incident?

Evaluation:

Students could write a short piece on the usefulness of oral history methodology, and how they would go about generalizing from interviews about a community.

Further Resources:

Diehl, Chad (Ed) (2023), Shadows of Nagasaki: Trauma, Religion and Memory after the Atomic Bombing, Fordham University Press

Gotō, Yōko, (2022) Gotō Rettō: Ritō wo tanoshimu, Tatsumi Shuppan.

McClelland, Gwyn, (2020) Dangerous Memory in Nagasaki : Prayers, Protests and Catholic Survivor Narratives, Routledge.

Miyamoto, Yuki, (2012) Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility after Hiroshima New York: Fordham University Press.

Perks, Robert; Thomson, Alistair Scott. (Eds) (2006). The Oral History Reader (2nd ed.). London UK: Routledge.

Portelli, Alessandro. (2009). What Makes Oral History Different. In: Giudice, L.D. (eds) Oral History, Oral Culture, and Italian Americans. Italian and Italian American Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230101395_2.

Treat, John, (1995). Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Urakawa, Wasaburō, (1973). Urakami Kirishitan Shi, Tōkyō: Kokusho Kankōkai.

Reference Images for Use:

Hamawaki Church and surrounds on Hisaka Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Hamawaki Church and surrounds on Hisaka Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

At the memorial site. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

At the memorial site. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Rōya no Sako. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, November 2022.

Rōya no Sako. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, November 2022.

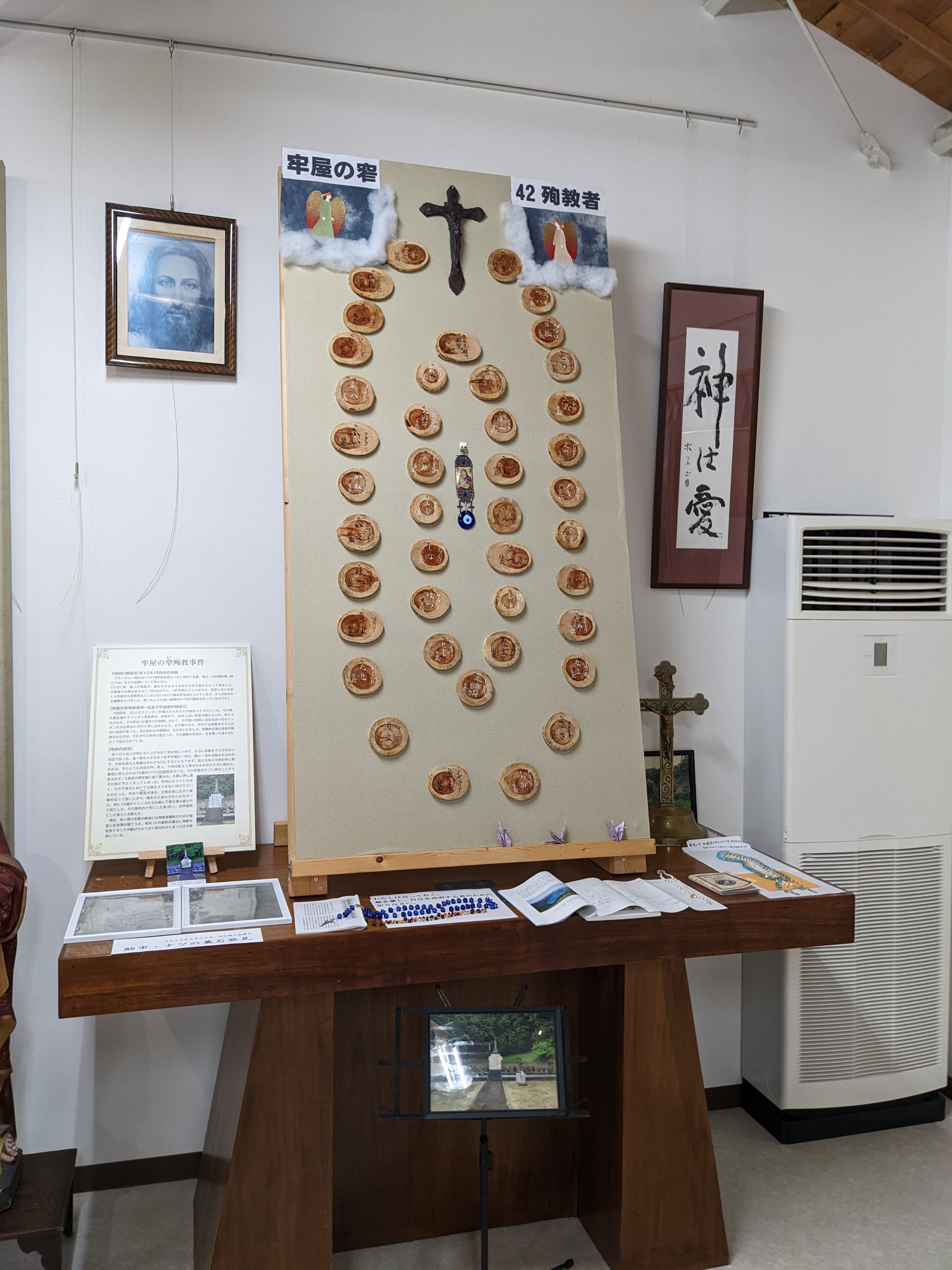

Memorial of Roya no Sako at the Catholic Museum on Hisaka Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Memorial of Roya no Sako at the Catholic Museum on Hisaka Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Credits/Acknowledgements:

Credit to Miyamoto Jitsuo and Fujie for the interview, and for their very generous hospitality during my visits to Hisaka. Also, thanks to Ryo Sasaki (Fukuoka), and Akira Nishimura (University of Tokyo) for their support in this project.