Hidden Christians & Oral History: The Name is the Lead

Save PDFLesson Plan: The Name is the Lead [Interview 3: Ozaki Natsuki]

Created by: Gwyn McClelland, University of New England; (assisted by Nobuko Sakatani and Satsuki Osaki, Gotō Islands).

Creation date: January 23, 2024

Keywords: World Heritage, Names, Discrimination, Consciousness, Identity

Interview 3: Ozaki Natsuki

Target Audience:

Undergraduate students, Graduate students

Duration:

1 hour, not including reading time

Learning Objectives:

Consider the interviewee's concept of self in this interview. Reflect on the interviewee's concept of "self," drawing on the discussion for this interview.

To consider how oral history can contribute to "power and empowerment." In conjunction with reading the interview and this teaching guide, you might also refer to Chapter 8 in Lynn Abrams' book Oral History Theory, "Power and Empowerment." Ozaki understands the naming of her ancestors as a discriminative historic act, but this knowledge apparently encourages her today. Why?

Potential Courses to Include this Lesson in:

Oral History

History

Japanese Studies

Asian Studies

Religious Studies

Required Materials:

interview (including audio stream), and photographs

associated readings

teaching guide, lesson plan

Activity/Procedure:

In preparation for the class first listen to Interview 3, and study the transcripts, referring to the vocabulary list as useful. Discuss your impressions of the interview as a class. Then, read the background information in this teaching guide. In small groups, discuss the learning objectives. There are further questions for discussion at the end of this guide.

Background:

Introduction to Interview:

Ozaki Natsuki 小崎なつき (pseudonym), was born in a small settlement on the coast of Wakamatsu Island in the Upper Gotō 上五島. In her interview I asked her about her consciousness of Hidden Christian ancestors and how that influenced her. She mentioned the impact of the 2018 World Heritage status and how she originally felt about it. She also explained about her original family name: Shimomine 下峰.

Community historian, Urakawa Wasaburō, was aware of a Meiji official's use of these names, noting that in the 6th year of the Meiji era, as the officials gave family names to commoners, and to geographical features and places, and that especially in Wakamatsu region, the official assigned keibu no imi 軽悔の意味 (insulting meanings) in the names that he dealt out to some of the peasants. Urakawa continues, such names usually included shimo 下, such as Shimomura (see Figure 1 below), Shimoda, and Shimozaki, and these were especially used in the Kiri-furugou area, not far from where Ozaki's family lived.1

As for Ozaki's thinking about gaps in her understanding of her family's history, "postmemory" is a theory that comes out of Holocaust memory as suggested by the scholar Marianne Hirsch, in which it is supposed that for many children and grandchildren of survivors of trauma it is in silences, and in gaps that intergenerational transmission of trauma occurs.2 We can identify something similar in this interview, where Ozaki remembers that her father alluded to the history of their mutual ancestor, without discussing the specifics. So, she felt that she had no choice but to research these missing pieces herself.

When she investigated, she found that the story contributed to her own consciousness of her identity as a Catholic descendant of the Hidden Christians. Ozaki goes on in the interview to explain to me the story of her ancestor that she researched after finding it in Urakawa Wasaburō's book of 1951, Gotō Kirishitan Shi.3 In this interview extract she describes what pages it is on in that book.

Her ancestor (5 generations back) was named Mineshita Jōhachi 峯下丈八. On investigating her ancestor's story, she writes in an email as follows:

"By the way, my great great grandfather (Mineshita Jōhachi) migrated to Fukumi at the time of the Urakami 3rd Persecution in 1856, at around the age of 33 years old. In 1870 (3rd year of Meiji) when they absconded from Fukumi, he was 49 years old. Eight people went on the boat. At the time running away from Fukumi were nine families and fifty people though, of which there was one more Mineshita family name, although I do not know if they were relatives. However, this was a common name in Fukumi region.

According to the Gotō Kirishitan Shi by Urakawa Wasaburō, the names of those who ran away from Fukumi were:

Hayashi Ikujirō

Mineshita Jōhachi

Mori Ikusaburō

Yana Otojirō

Mineshita Tsunekichi

Iwamoto Sōichi

Iwamoto Yūsuke

Mori Nizō"

It seemed that it could be possible that one Gotō Islander, Mineshita Konshichi 峰下今七, who is mentioned in the narratives was related to Ozaki's ancestor, Mineshita Jōhachi 峰下丈八. That is especially because of the similarity in names, including a number in their first names. I told her about this young twelve or thirteen year-old and how he had been taken by a young missionary Jule-Alphonse Cousin on an incredible journey to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and eventually to a seminary in Penang. Eventually she got back in touch, and said while he could well be a relative, it seems to be impossible to be sure that he is actually related, as there were many people with the same name in the region Fukumi in those days, and her ancestral family had so many people in it.

In an English-language book called The Martyrs of Nagasaki by Frederick Williams, published in 1956, the author wrote:

"When the first of the Urakami Christians were rounded up and deported – 114 of them – Bishop Petitjean became alarmed and was afraid of taking any further chances of his young scholastics being led to the martyr's (sic) block. He packed them off quietly to the General College of the Society of Foreign Missions at Pulo Penang in the care of Father Cousin, their mentor."4

Mineshita Konshichi was taken on the boat out of Nagasaki with Cousin. Along with eight students from Urakami, and one from Hirado, he had travelled to Nagasaki on the 28th July 1868, in order to be schooled by the French missionaries and went on a "foreign boat" on to Shanghai and on to Hong Kong, before falling so sick he died there. Father Cousin and Poarie were involved in the scheme to spirit these young people away to study outside Japan. In Urakawa’s history there is a photograph of the young students with the youthful looking missionary Cousin, with the caption, "The Latin students led by Teacher Cousin who escaped to Shanghai."

In the interview, Ozaki also mentioned a location in the southern part of Nakadōri Island, called Kiri, and the Kirishitan caves as important sites of memory.

1 Urakawa Wasaburo, Gotō Kirishitan Shi, 166-167. In the earlier period of missionization, when the Jesuits were in Japan in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, genin 下人 was a term used to denote "lower people," or those of lower status, and therefore often referred to "bondage," similar to slavery. See Rômulo Ehalt. "Geninka and Slavery: Jesuit Casuistry and Tokugawa Legislation on Japanese Bondage (1590s–1620s)." Itinerario 47, no. 3 (2023): 342–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115323000256.

2 Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

3 Wasaburō Urakawa, Gotō Kirishitan Shi (Tōkyō: Kokusho Kankōkai, 1973).

4 Frederick Vincent Williams, The Martyrs of Nagasaki (Academy Library Guild Fresno, Calif. 1956), 110.

Discussion Questions:

Does this interview extract assist you in understanding the concept of postmemory? If so, how do you understand it in Ozaki's case, and can you think of any other examples in historiography?

How does Ozaki relate the announcements of Hidden Christian World Heritage sites to her own identity?

How does the overt naming of the peasants contribute to understanding their historical oppression? Why does Ozaki use this "naming story" as a part of explaining the history in her tour-guide job?

Why do you think people who are related to/descended from Hidden Christians may have been unsettled by the ratification of Hidden Christian Cultural World Heritage sites in 2018?

Evaluation:

Students should write a short piece about how discrimination can become a point of pride. Is this always the case? Why or why not?

Further Resources:

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Nakajima, Kō and 中島功. Gotō hennenshi / Nakajima Kō cho Kokusho Kankōkai, Tokyo, 1973.

Urakawa, Wasaburō 浦川和三郎. (1928). Kirishitan no Fukkatsu, 2 vols. キリシタンの復活. Tokyo: Kokushokankōkai 国書刊行会, 1979 (first published in 1928).

Urakawa, Wasaburō. Gotō Kirishitan Shi. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, 1973.

Williams, Frederick Vincent, 1890-. The Martyrs of Nagasaki Academy Library Guild Fresno, Calif. 1956.

Reference Images for Use:

Many names of those descended from Hidden Christians in the region of Wakamatsu and southern Nakadōri include the character 下 like this one on a Catholic grave, with the family name Shimomura, 下村. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2023.

Many names of those descended from Hidden Christians in the region of Wakamatsu and southern Nakadōri include the character 下 like this one on a Catholic grave, with the family name Shimomura, 下村. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2023.

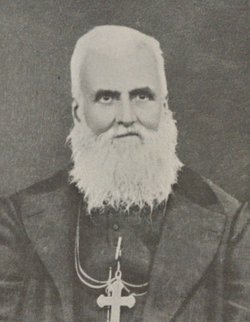

Jule-Alphonse Cousin クザン神父 (1842–1911), MEP, Later in life. Public domain.

Jule-Alphonse Cousin クザン神父 (1842–1911), MEP, Later in life. Public domain.

Cousin MEP with the young students including Mineshita who went with him to study to Shanghai and then Hong Kong, Urakawa, Kirishitan no Fukkatsu, 1928. Public domain.

Cousin MEP with the young students including Mineshita who went with him to study to Shanghai and then Hong Kong, Urakawa, Kirishitan no Fukkatsu, 1928. Public domain.

Credits/Acknowledgements:

Credit to Ozaki Natsuki for the interview and research about her family. Also, thanks to Ryo Sasaki (Fukuoka), and Akira Nishimura (University of Tokyo) for their support in this project.