Hidden Christians & Oral History: The "Kakure"

Save PDFLesson Plan: The "Kakure" (Interview 5: Kakimori Kazutoshi)

Created by: Gwyn McClelland, University of New England; (assisted by Nobuko Sakatani and Satsuki Oosaki, Gotō Islands)

Creation date: January 23, 2024

Keywords: Hidden Christians, death, spirituality, Ignatius, Kakure

Interview 5: Kakimori Kazutoshi

Target Audience:

Undergraduate students, Graduate students

Duration:

1 hour, not including reading time

Learning Objectives:

To understand the structure of Kakure Hidden Christian societies

To consider the importance of the lunar versus solar calendar for the Hidden Christian societies by the example on Naru Island

To discuss the concept of "acculturation" which is understood as syncretism by some scholars, or as hybridity by others

Potential Courses to Include this Lesson in:

Oral History

History

Japanese Studies

Asian Studies

Religious Studies

Required Materials:

interview (including audio stream), and photographs

teaching guide/lesson plan

Activity/Procedure:

In preparation for the class first listen to Interview 5, and study the transcripts, referring to the vocabulary list as useful. Discuss your impressions of the interview as a class. Then, read the background information in this teaching guide. In small groups, discuss the learning objectives below. There are further questions for discussion at the end of this guide.

Background:

The distinction that designates the difference between Hidden Christians as Sempuku (pre-1873) and kakure (post-1873: see also the introduction to this website) is especially important within this interview. There are two names in Japanese for Hidden Christian: Sempuku and Kakure. Sempuku Kirishitan is used by scholars to delineate the time before the persecutions finished. Kakure Kirishitan is used to denote those who did not return to Catholicism after 1873. Kakimori Kazutoshi is an activist who worked to support the World Heritage registration of Hidden Christian sites in the Nagasaki and Amakusa area, and he is also a researcher in his retirement.

Kakimori is the secretary for the Society for Research on Kirishitan During the Persecution 禁教期のキリシタン研究会. In this interview excerpt he expresses disappointment at the exclusion by World Heritage sites of excluded Kakure places of life and memory, in favor of those sites where Catholicism reemerged following persecutions after 1873. Thus, on Naru Island, the World Heritage site is to be found at Egami village, where there is a Catholic Church, even though there were multiple and more representative Kakure communities on this island, where Hidden Christian Kakure practices continued post-1873.

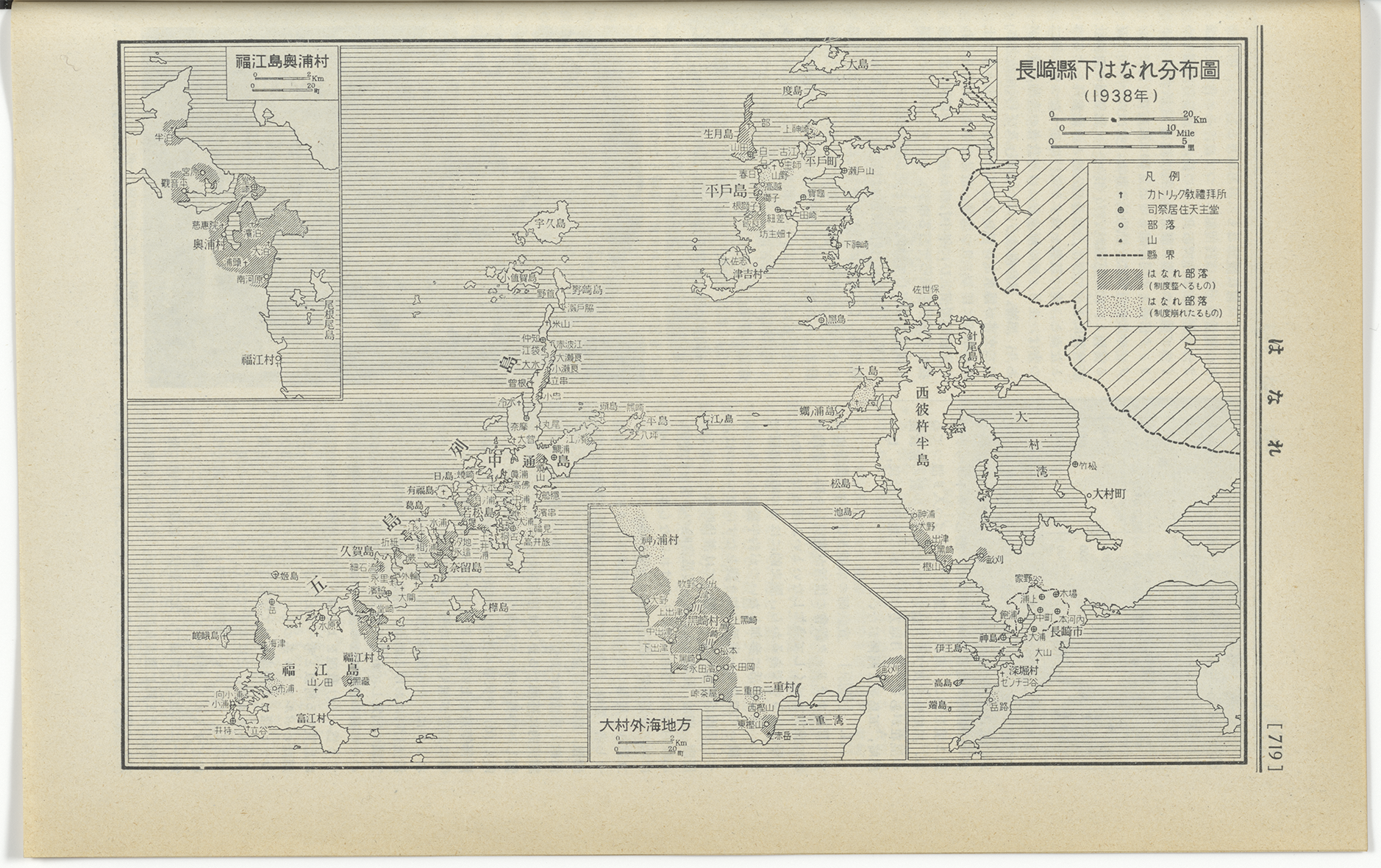

See the "Hanare map" below from 1938, which describes the distribution of Hanare, who today are generally regarded by scholars as Kakure. You can see on this map that through most of the twentieth century there were Kakure, who continued the practices of their ancestors as Hidden Christians. On this map, there are both "continuing system" Hanare, and "system breaking down" (崩れたるもの) Hanare groups identified. Look closely and you can see that in the Gotō Islands, Naru Island has the most "continuing system" Hanare groups according to the researchers. This map appeared in the Catholic "comprehensive dictionary" published in 1940.

As Kakimori explains in this interview, in the majority of the Hidden (Kakure and Sempuku) Christian societies, there were three men who were entrusted with roles to ensure the community continued to remember their Christian origins. In many villages, they were called the chōkata, mizukata and shukurō, although the third name varied across the different groups. Kakimori Kazutoshi's maternal grandparents' ancestors arrived on Naru Island from Konōra, Sotome in around 1800 and settled in a place called Kashinokiyama. In the village of his maternal grandparents, Kakimori's great uncle, Domeges Iwamura Yoshinobu, was the village chōkata, the "keeper of the book," as the translation puts it in the recent Hidden Kirishitan Illustrated. The chōkata role included writing the calendar for each year for the community.1

Kakimori's maternal grandparents' ancestor, Sankichi, came from Kashiyama Village, Sotome, Mie. His maternal grandfather was the mizukata baptizer, or "keeper of the water." In recent years, Kakimori Kazutoshi started a Kakure Kirishitan resource center and moved to Akogi, the location of the village of his maternal grandparents on Naru Island. He was born there in 1946 before he moved to live in Nagasaki city to attend school. Every summer holiday he came with his family to Naru Island for one month.

In this interview excerpt, Kakimori talks about the importance of the sanyaku, the "three roles" mentioned above, which transmitted Kakure Kirishitan prayers, dates, baptism, and confession (konchirisan). As noted above, the three roles include the chōkata (keeper of the book), the mizukata (baptizer) and the shukurō, who acted as an assistant to the other two.

He also discusses the importance of the calendar, kept by the chōkata, which he notes had to be transferred from a solar to a lunar calendar. When the so-called Nijūsanya machi 二十三夜待ち (Waiting for the 23rd night) was celebrated in Japan, he explains, the Kakure Kirishitan prayed to Saint Loyola Ignatius. Nijūsanya machi has various traditions across Japan, in both Buddhist and Shinto cosmologies.

While Kakimori has been baptized as a Catholic, he identifies strongly with his Kakure Hidden Kirishitan roots, and his resource center serves as a place to collect artifacts, photos and maps, and to encourage visitors to find out more about the history. When I visited Kakimori in the Japanese summer heat of August 2023, he had a group of tourists descend on his small place with two cars. He told me that he likes people to ring ahead for an appointment to visit his museum, but when they turn up he does not want to disappoint, so he opens the museum and shows them through.

Kakimori has written about Yagami, the Hidden Christian village that his friend, Urakami Sachiko originates from. Additionally, in the last few years, he has initiated and supported an "Ignatius Festival," bringing people back to the islands to celebrate the heritage of the people here.

1 Gonoi, Hidden Kirishitan Illustrated 潜伏キリシタン図譜, 212. See also "Otaiya", a documentary filmed by Christal Whelan and published in 1997 that includes the Otaiya ceremony with Kakimori's deceased uncle, Iwamura Yoshinobu. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/otaiya

Discussion Questions:

How does Kakimori distinguish between Sempuku and Kakure in this interview?

Why does he believe that Kakure Kirishitan have been excluded from the World Heritage listing of 2018? Explain.

How does Kakimori understand the Kakure Kirishitan's veneration of saints and their use of Buddhist or Shinto elements in their religious practices? Do you agree with him that they did NOT mix religions? Why/why not? You may like to read some other scholars work on this topic, such as Turnbull or Whelan in the additional readings. Whelan worked on Naru Island in the 1990s.

Evaluation:

Students could write a short piece summarizing their understanding of the Kakure Kirishitan societies from this interview, and their practices that included the calendar and rituals. They could also discuss their own understanding the concepts of "acculturation," syncretism, or hybridity.

Other Sources/References:

Turnbull, Stephen R. Japan's Hidden Christians, 1549–1999. 2 vols. Richmond, Surrey: Japan Library and Edition Synapse, 2000.

———. The Kakure Kirishitan of Japan: A Study of Their Development, Beliefs and Rituals to the Present Day. Richmond, Surrey: Japan Library, 1998.

Whelan, Christal. "Japan's Vanishing Minority: The 'Kakure Kirishitan' of the Gotō Islands." Japan Quarterly 41, no. 4 (October 1, 1994): 434–49.

———. "Religion Concealed. The Kakure Kirishitan on Narushima." Monumenta Nipponica 47, no. 3 (1992): 369–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2385104.

———. "Written and Unwritten Texts of the Kakure Kirishitan." In Japan and Christianity, edited by John Breen and Mark Williams, 122–37. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24360-0_9.

———. "Otaiya" documentary, 1997, https://vimeo.com/ondemand/otaiya, accessed 23rd January 2024.

Reference Images for Use:

View from Hidden Kirishitan Resource Center at Akogi, Naru Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

View from Hidden Kirishitan Resource Center at Akogi, Naru Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022. "Hanare" (Kakure) map of the Nagasaki region, including the Gotō Islands, 1938, Katorikku Daijiten, vol. 1, 1940. Courtesy of National Library Australia.

"Hanare" (Kakure) map of the Nagasaki region, including the Gotō Islands, 1938, Katorikku Daijiten, vol. 1, 1940. Courtesy of National Library Australia.

Kakimori's maternal ancestors lived in Akogi: Akogi bus-stop on Naru Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Kakimori's maternal ancestors lived in Akogi: Akogi bus-stop on Naru Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Akogi Kakure Kirishitan no sato 阿古木隠れキリシタンの里 on Naru Island Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Akogi Kakure Kirishitan no sato 阿古木隠れキリシタンの里 on Naru Island Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Credits/Acknowledgements:

Credit to Kakimori Kazutoshi for the interview, and his generous hospitality during my visits to Naru. Also, thanks to Ryo Sasaki (Fukuoka), and Akira Nishimura (University of Tokyo) for their support in this project.