The Tea Ceremony as a Culinary Experience: Matcha, Sweets, and Kaisekiby Eric C. Rath

Fundamentally, "the tea ceremony" (chanoyu) is about food. Take away the tea, and you are left with "ceremony," a vague term with possible religious undertones. Tea (the beverage) defines the ceremony of tea, and preparing and drinking tea—and eating—are central to experiencing it. Even in practice sessions, tea students make bowl after bowl of tea while others take turns drinking the tea, often after eating a tea sweet. Learning the way of tea includes developing an appreciation for the powdered green tea called matcha. There is also a lot to learn about how tea sweets express cultural history and seasonality. Even someone who has never stepped into a tearoom might know that the most expensive Japanese restaurants in Kyoto, New York City, São Paulo, or elsewhere serve a style of meal called kaiseki that is said to have its roots in the meals of the tea ceremony. Kaiseki is one example of how the foods of the tea ceremony have spread to become part of global food culture at a time when matcha, the finely ground tea used in the ceremony, is more likely to be found in baked goods, a matcha latte, or ice cream than in a tea bowl. The aim of this short essay is to show the roots and place of matcha, confectionery, and kaiseki in the tea ceremony, with the idea that later essays can examine each one of these topics in greater detail.

Matcha

Until the late eighteenth century, tea drinkers and biologists in Europe thought that green tea came from a different plant than black tea. That was the view of the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1708), the scientist who devised a system of classifying living organisms. However, both green and black tea are from the same plant (Camellia sinensis), which is native to southeast China. Black teas are oxidized: the leaves are rolled and exposed to air, which breaks down chlorophyll and releases tannins. Green tea skips oxidation and instead the leaves are heated to preserve their color. Since the late sixteenth century in Japan, the tea for matcha was grown under shade awnings which caused the leaves to have more chlorophyll, a darker color, and higher concentrations of theanine, an amino acid, which like monosodium glutamate, imparts umami, the savoriness indicative of many Japanese foods.

As early as the seventh century, the Japanese cultivated tea bushes imported from the continent, but the creation of powdered tea had to await the arrival of the tea mill, which came to Japan in the second half of the thirteenth century. Tea mills and the whisks used to dissolve the resultant talcum-like powder in hot water both came from China, and powdered tea consumption spurred the growth of commercial tea production in Japan in the late fourteenth century. Matcha did not become more widely consumed until a century later, and people drank it in a much wider context than the tea ceremony. Shoppers in the marketplaces of medieval Kyoto could pay a coin for a bowl of matcha.

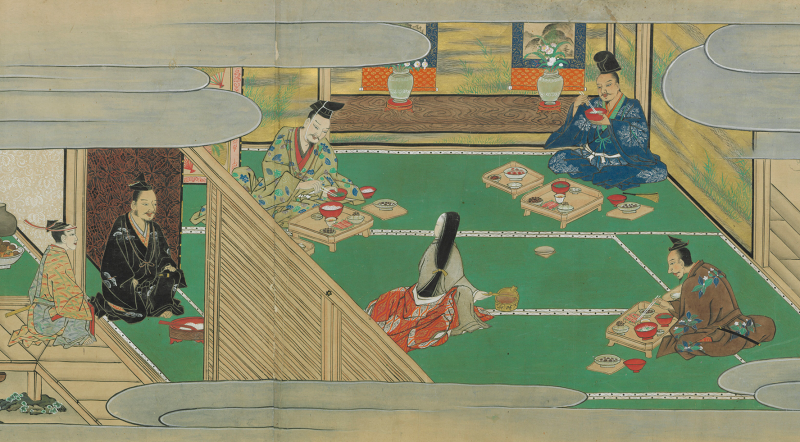

The above image from The Illustrated Rat's Tale (Nezumi no sōshi emaki 鼠草子絵巻), created between 1550–1650, shows the preparations for a wedding banquet in the story of a rat lord who wants to marry a human bride. In the upper register, the centrally located rat turns a tea mill while the rat to the right, who wears a red hat and is meant to represent the tea master Sen no Rikyū 千利休 (1522–1591), inspects tea utensils.

Tea Sweets

The Japanese word for "sweets" (kashi) literally means fruits and nuts, and in the early days of tea ceremony in the sixteenth century, tea masters served tangerines and chestnuts as well as savory foods like sardines, konbu, and wheat gluten (fu) as tea sweets. Imported sugar had been known in Japan as an expensive medicine for centuries, but that sweetener was not used in confectionery until the second half of the sixteenth century, when it was re-introduced by Portuguese merchants who taught the Japanese how to work with the sweetener to make candies, cookies, and baked goods—versions of which became part of the traditional Japanese confectionery repertoire. In the seventeenth century, confectioners developed sweets for the tea ceremony by combining sugar with glutinous rice flour, adzuki beans, and colorings. Confectionery shops became a typical sight in cities by the end of that century.

The confections used for tea sweets fall into two categories: dry sweets (higashi) and moist sweets (namagashi). Dry sweets like rakugan have less than ten percent water content. Rakugan, which first appears in tea writings in the 1640s, is made from rice flour and sugar and is pressed with a mold into a variety of shapes.

Moist sweets, like those made from mochi or mizu yōkan, have between thirty to forty percent water content. Mochi-sweets (mochigashi) combine glutinous rice flour with adzuki beans to form a paste that can be colored and molded into different shapes and often stuffed or coated with a paste made from adzuki. Confectioners make mizu yōkan by combining adzuki paste with sugar and agar agar to make a firm gelatin that can be sliced into pieces. In the tea ceremony, dry sweets are used for thin tea, which contains less tea relative to water, and moist sweets for thick tea, which contains a higher concentration of tea to water.

Given that the ingredients for tea sweets can be shaped and colored into countless forms to look like flowers, small fruits, or more abstract designs, the names of the sweets are critical for unlocking their meaning. As more confectionery shops opened in the seventeenth century, the number of names for sweets proliferated, revealing how sweet makers attempted to differentiate their products. Appreciating a tea sweet might begin with the sweet's appearance or taste, but the name of the sweet gives the overall meaning to it. A sweet that looks like a small tangle of pink and white spaghetti might be indecipherable were it not for the name "hydrangea," which evokes the cool feeling of a spring or summer morning, a feeling reinforced by the dew-like pieces of translucent kanten that adorns it. The host selects sweets based on seasonality and to fit in thematically with the rest of the tea gathering.

Kaiseki

Kaiseki can refer to the meal served at a tea gathering or a dining experience at an elite Japanese restaurant. This ambiguity works to the advantage of the restaurant chef, who can reference the culture of tea in the aesthetics of their cuisine in various fashions (such as in the way they plate food). Tea practitioners often contrast restaurant kaiseki with the simpler fare appropriate for the tea room by writing tea kaiseki with the Japanese characters meaning "warming stone" (懐石), a supposed reference to the hot rock that is kept in a Zen monk's robes to stave off hunger. If a hot rock can satisfy an appetite, then the small servings of food offered at some tea gatherings should suffice. This way of writing kaiseki conveniently links the way of tea with Buddhism and evokes images of ascetic practice. But this way of writing kaiseki and the story it evokes both date to the late 1600s, more than a century after tea ceremonies started featuring meals. Wider popularization of writing kaiseki as warming stone began in the Meiji period (1868–1912). In the 1500s, when the way of tea was beginning, tea practitioners used the term "menu" (kondate or shidate) to refer to their tea meals, or they called those meals "kaiseki" but wrote that word with characters meaning "sitting together" (会席), a term long used to refer to gatherings for composing poetry and drinking sake. In the early modern period (1600–1868), two forms of kaiseki developed: tea kaiseki and a version of restaurant-style dining also called kaiseki, which consisted of a meal served in a series of courses and started becoming prevalent in the mid-nineteenth century.

Besides these two elite styles of dining, Japan saw a booming food retail trade in cities in the early modern period. Shops and pushcarts in the seventeenth century sold soba and udon day and night. Townspeople could purchase prepared foods for carryout at stands where everything sold was conveniently the same price. Izakaya sold foods like grilled tofu to accompany sake, and some izakaya offered carryout foods as well. Tempura and sushi developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries into foods that could be eaten while standing in the street or taken home.

Men with money—and dining out was a male pastime in Japan until the twentieth century—could afford the high-class restaurants that flourished in cities, such as those in the licensed prostitution area of Yoshiwara in Edo (Tokyo) in the 1680s. There men could indulge their gastronomic fancies in brothels (ageya) that included extensive kitchens. The foods served in these establishments were not kaiseki but variations on two forms of elite dining that were also historically influential for the development of kaiseki: "main tray" (honzen) cuisine and the foods served at drinking parties called sakamori. Both of these elite modes of dining developed in the fifteenth century. Honzen was a banqueting style that remained the most formal way of eating until the late nineteenth century, and it is still used on occasion today, such as at weddings and during ceremonies in Japan. Drinking parties (sakamori) took place after honzen banquets or whenever participants desired.

Honzen dining developed in the 1400s as a style of banqueting that catered to status-conscious samurai and aristocrats. Guests would sit on the floor and use small personal tables for dining, squat square trays with short legs that raised them off the ground. The "main tray" (honzen), which was placed directly in front of the diner, lent its name to this style of dining. At minimum, the main tray contained rice, soup, chopsticks, and a precursor to sashimi called namasu, which is a mixture of raw seafood and other items with a vinegar dressing. For some, a single tray sufficed for an ordinary meal, but banquets featured multiple trays of food served simultaneously to the same guest depending on their status. Three, five, or seven trays in total formed typical servings, with trays placed on either side of the main tray and beyond it just within the diner's reach. Each tray featured a hot or cold soup and side dishes. More dishes could be placed on the floor near each guest. Even the hungriest diner could not consume everything, and there were certain dishes included on trays that were purely decorative and not meant to be eaten. Game fowl, for instance, were served with their wings attached poised as if the birds might fly away from the table. Honzen cuisine was an exercise in conspicuous consumption, or perhaps non-consumption since many foods were meant only for display.

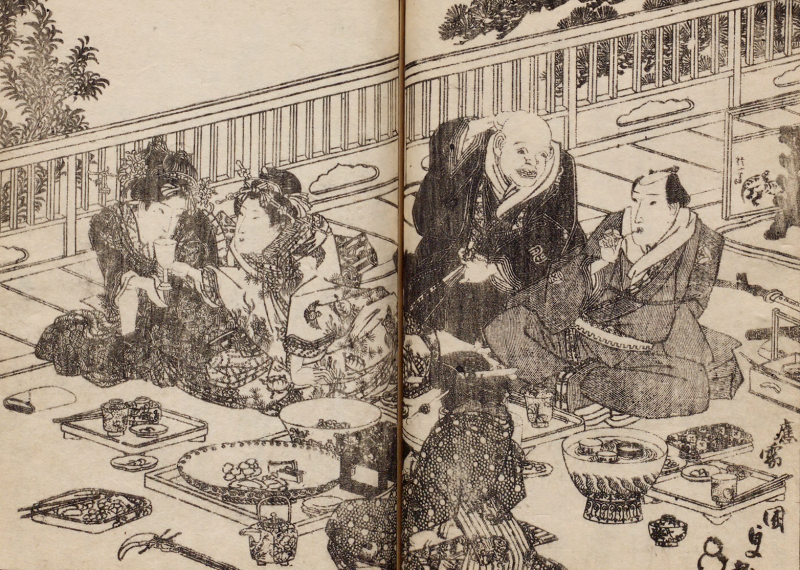

At their most formal, honzen banquets began with a drinking ceremony in which the host invited the principal guest into a smaller room and bonded with them by drinking sake from the same cup. The host also bestowed lavish gifts on their guest, such as armor and weapons. Moving to a larger room the drinking paused, or at least continued at a slower pace, during the honzen banquet. Afterward the participants moved to a different setting for more sake drinking. During the drinking party (sakamori), and in the relaxed setting, guests could eat, drink, and converse freely with each other, paying less attention to status differences. Fancier parties featured various entertainments. Honzen dining was used in restaurants from the early modern period to the nineteenth century, as an illustration from the book The Gourmand (Ryōritsū 料理通) shows. At more casual dining experiences, customers took food from shared vessels in the style of medieval drinking parties.

A full honzen banquet would never fit into a tea room, so in the late sixteenth century tea masters reduced the number of trays and dishes served, and they preferred using trays without legs. Pared down to the basics, tea kaiseki consists of rice, soup, and mukozuke (sashimi) on a tray called an orishiki or oshiki. Beginning with the mukōzuke, guests sample a different part of the meal with each serving of sake. Unlike a honzen meal, where all of the foods appear simultaneously, dishes are brought out sequentially for a tea meal so that they can be served hot. After the mukozuke, the next item served is a dish of simmered foods (wanmori) followed by something grilled (yakimono) like fish. An additional soup called an atsumono follows, and a small tray of delectables (hassun) is then offered to pair with sake. Tea sweets come next as a prelude to the tea that follows. The simplified format of tea dining known as "one soup and three side dishes" (ichijū sansai), which is often mistakenly attributed to Sen no Rikyū, developed in the early modern period after his lifetime.

Sometime in the mid to late nineteenth century, restaurants moved away from honzen meals and toward serving dishes consecutively in the manner of tea kaiseki, and they called this mode of restaurant dining kaiseki. Usually held in a restaurant, sake drinking begins immediately when the guests take their seats. Then servers bring out dishes in the typical order of small bite appetizers (sakizuke), a dish of simmered foods, sashimi, something grilled, a sampling of side dishes, and a dish with a variety of ingredients that are usually flavored with vinegar. Rice, miso soup, and pickles are the last savory foods served as a conclusion to the meal, but these can be followed by fresh fruit or a tea sweet.

Both tea and restaurant kaiseki are elite forms of dining. The Japanese government originally sought to have kaiseki listed as an example of "intangible cultural heritage" with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) but later rethought that application after concluding that kaiseki was too elitist. Instead of submitting kaiseki, the government revised their application to define washoku, "the traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese," taking a more broad-based and vague representation of the Japanese food culture passed down in daily life and in festivals, which UNESCO added to its list of intangible cultural heritage in 2013.

References and Suggestions for Further Reading

Cang, Voltaire. "Unmaking Japanese Food: Washoku and Intangible Heritage Designation." Food Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5, no. 3, (2015): 49–58.

Farrer, James, Mônica R. de Carvalho, and Chuanfei Wang. "Reinventing Japanese Fine Dining in Culinary Global Cities." In The Global Japanese Restaurant: Mobilities, Imaginaries, and Politics, edited by James Farrer and David L. Wank, 289–327. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2023.

Farris, William Wayne. Bowl for a Coin: A Commodity History of Japanese Tea. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2019.

Rath, Eric C. Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

–––. Japan's Cuisines: Food, Place and Identity. London: Reaktion Books, 2016.

–––. "The Magic of Japanese Rice Cakes." In Routledge History of Food, edited by Carol Helstosky, 3–18. New York: Routledge Press, 2015.

–––. "Sex and Sea Bream: Food and Prostitution in Hishikawa Moronobu's 'A Visit to the Yoshiwara.'" In Seduction: Japan's Floating World: The John C. Weber Collection, edited by Laura W. Allen, 28–43. San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, 2015.

–––. "What Rats Reveal about Cooking in Late Medieval Japan." Gastronomica: The Journal for Food Studies 23, no. 3 (2023): 74–83.

Rath, Eric C. and Takeshi Watanabe. "Amai: Sweets and Sweeteners in Japanese History." Gastronomica: The Journal for Food Studies 23, no. 4 (2023): 1-6.

To cite this page:

Rath, Eric C. "The Tea Ceremony as a Culinary Experience: Matcha, Sweets, and Kaiseki." Teaching Tea: Culture, History, practice, Art on Japan Past & Present. 2025. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/teaching-tea-culture-history-practice-art/resources/the-tea-ceremony-as-a-culinary-experience-matcha-sweets-and-kaiseki