How to Read a Teabowl: Chanoyu Principlesby Meghen Jones

Revered by potters, tea practitioners, and collectors worldwide, the teabowl (chawan) today represents something of a Holy Grail.

While a teabowl may be considered art, at its most basic, a teabowl is a vessel for preparing and consuming the powdered, whisked green tea known globally today by its Japanese name, matcha. The simplest of forms—a bowl the size and shape of two conjoined cusped palms—a teabowl may contain multitudes, from the artistry of an individual maker to a myriad of cultural and social values. Like a tea leaf storage jar or a tea caddie, a teabowl performs an essential function within chanoyu (literally "hot water for tea"), the procedure for preparing and drinking matcha and the social gathering within which it takes place. Codified in sixteenth-century Japan, chanoyu is now a global practice. Over the last century, the teabowl has transformed from utilitarian vessel to an iconic instrument of both cultural preservation and artistic innovation. The only implement in chanoyu handled by both host and guest, teabowls are used and appreciated within chanoyu practice today according to a set of identifiable, shared approaches. This essay provides a primer for how to understand chanoyu teabowl fundamentals according to basic elements, use, and aesthetic tropes.

Fundamental Attributes

For ease of use and appreciation in chanoyu, teabowls share certain formal attributes. As we see in the Raku Sōnyū example, most teabowls are glazed ceramic, for durability and ease of use. Metal, glass, and lacquered wood are also occasionally used. The teabowl's form evolved in China, first for teas that incorporated spices and flavorings and achieved a soup-like consistency, hence a bowl form.

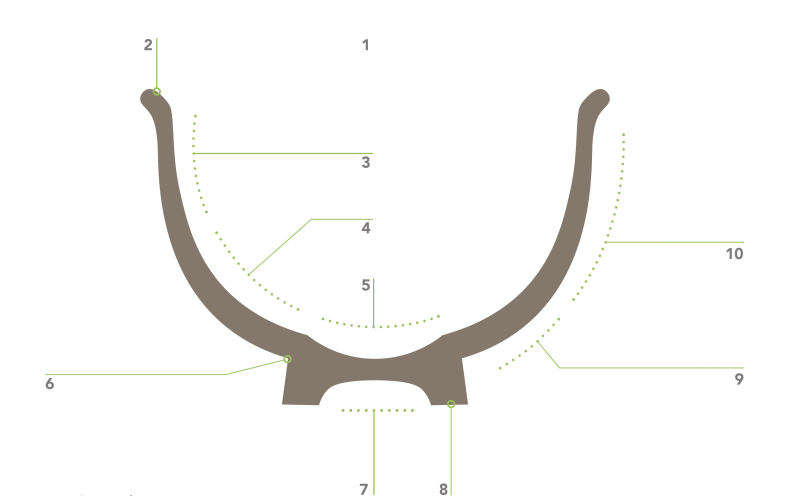

Over the centuries, makers and users have evolved teabowl appreciation to incorporate many nuanced aspects. According to contemporary standardized chanoyu protocols, teabowls are often evaluated and appreciated according to the following parts (Fig 3):

View of the interior (mikomi 見込み)

Lip (kuchitsukuri 口造り)

Where the cloth wipes (chakinzuri 茶巾摺)

Where the bamboo whisk tines touch (chasenzure 茶筅摺)

Tea pool (chadamari 茶溜まり)

Area just above the foot (kōdai waki 高台脇 )

Area inside the foot (kōdai ura 高台裏 )

Foot (kōdai 高台, literally "elevation")

Hip (koshi 腰)

Torso (dō 胴)

Also important is that teabowls are generally understood to have a "front" and a "back," the former discernible through particular elements such as surface decoration or firing effects. While referring to vessel parts in corporeal terms is not unique to teabowls or East Asia, distinct to teabowl nomenclature is attention to areas of the bowl that other utensils touch. Accorded particular attention in ascertaining the artistry of the maker is the foot and lower portion of the vessel, important in establishing how the bowl feels in the hands—its weight, sense of balance, and transmittal of the matcha's warmth. Appreciating a teabowl's exterior often involves the admiration of any landscape (keshiki) visualization resulting from the effects of fire (higawari) or the kiln (yōhen) on the bowl. Teabowl formal attributes are thus both visual and haptic, and are understood and evaluated through their use.

Unwrapping a Bowl

A storage box for a teabowl serves as protection and as a conveyor of important pieces of information about it that are useful to a host when choosing utensils (Fig 4). This process is known as toriawase, literally "selecting and combining," and is carried out in consideration of the identity of the guests and distinctions of the moment, such as seasonality. Usually secured with a cotton ribbon tied in a slip knot, as we see with the box for Eboshi, the box safeguards the physical integrity of the teabowl, something that is particularly important in a country prone to earthquakes such as Japan. It is usually made of a lightweight paulownia wood that repels light, moisture, and insects. Inside, the teabowl may be wrapped in an orange turmeric-colored cloth (ukon-nuno) or a bag made of silk or brocade (shifuku), as we see for Eboshi. The box lid or side may convey the maker and object's name, and any other important information concerning provenance or the like, through artfully brushed calligraphy and impressed stamps.

Eboshi bears such an inscription on the obverse of its lacquered paulownia wood storage box lid (Fig 5). There, we read that the potter Sōnyū (Raku Sōnyū, or Kichizaemon V) made this black teabowl bearing the name "eboshi," a type of hat worn by Heian period (794–1185) courtiers, in the year of the water snake (mizunotomi)—according to the Chinese sexagenarian cycle calendar—which corresponds to the Gregorian calendar's 1713. Names of three heads of the Omotosenke school of tea are also inscribed by a calligrapher, serving to endorse its authenticity, and the inscription concludes with the character kotobuki 寿, expressing felicitations.

Using a Teabowl

Chanoyu practitioners prepare and consume tea in teabowls in prescribed ways according to tea types and schools. The host wipes the teabowl in a particular way with a cloth called a chakin. The tea's preparation then differs depending on whether thin tea (usucha) or thick tea (koicha) is being served. For thin tea, the host places two or three small scoops (about two grams) of matcha in the bowl, and, depending on the desired strength, adds about a half ladleful (about sixty milliliters or a quarter cup) of hot water (at approximately 80°C). The tea is then infused into the hot water with a bamboo whisk. Thick tea requires the host to add about twice as much tea (typically about four grams of the highest quality matcha), mixed with slightly less hot water (about fifty milliliters). The choice of teabowl also varies by tea type. Thin tea is often served in more decorated bowls, while thick tea typically calls for Chinese Jian ware (or Jian-ware style) bowls; Korean teabowls (kōrai chawan); or Raku, Hagi, or Karatsu Japanese teabowls. The exact procedures for preparing and serving tea vary among different schools of tea and have evolved over time. One example is the contrasting approach to whisking thin tea: Urasenke teachings call for foam, whereas Omotosenke teachings do not. However, the major tea schools all conform to the following sequence of steps for drinking tea in a formal manner:

Bow to the host.

Pick up the bowl and place it in the left palm, bracing it with the right hand.

Turn it halfway around to drink from the back of the bowl.

Raise the teabowl in a gesture of appreciation.

Sip the tea.

Turn the bowl back so the front is facing you, and return it to the tatami mat.

Observe, feel, and talk about the teabowl's qualities.

The latter includes consideration of the parts of the bowl as listed above.

Tea practitioners perceive a bowl's visual and haptic properties through a multisensory engagement of the body. Let us again use Eboshi as an example (Fig 1). Two hands cradle it comfortably, noting its weight. The warmth of the tea transfers through the bowl, and we may become aware of a particular nestling sensation in the hands resulting from Eboshi being hand-formed, not wheel thrown. The surface of a glazed bowl is usually smooth, but may have perceptible textural qualities such as, here, the texture of an orange, with pits formed in the glaze during firing. Its rough kase glaze, so named for resembling a kettle's surface, draws the users' attention to its natural irregularities. The interior provides ample space for whisking tea. As a guest, we drink from its undulating lip, and after doing so, take time to appreciate it in whole, and may turn it over to gaze at the handmade qualities of the foot, which, in the case of Eboshi, resembles a small peak (Fig 6). The bowl thus reveals itself not as a static object but as a dynamic presence whose qualities unfold through a carefully orchestrated engagement with it.

Types of Teabowls

Chanoyu practitioners generally divide teabowls into three categories according to national styles: Chinese, Korean, and Japanese, or karamono, kōrai chawan, and wamono.

Chinese teabowls were the first ones used in Japan, imported by Zen monks in the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and coveted by later connoisseurs for their beauty, technical virtuosity, and connection to what was perceived as an all-powerful China. These smooth, thin-walled, symmetrical, and conical bowls with high-fired brown or black glazes became known in Japanese as tenmoku, after Tianmushan (Mt. Tianmu), a mountain in Fujian near several of the monasteries that used them. Potters covered these bowls with even, iron-saturated, highly viscous glazes before firing them to up to 1350° Celsius, resulting in shiny vitrified black and brown surfaces as we see in one famous example, a Jian ware bowl made in Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) China that subsequently entered a Japanese collection and in 1951 was designated a Japanese National Treasure (Fig 7). Its gold band exemplifies the Chinese practice of covering thin, rough-edged rims bearing uneven coatings of glaze with silver or gold bands that also serve to adorn them decoratively. Typically, teabowls in the Chinese style are used in chanoyu with stands called tenmokudai, often made of lacquered wood, in order to stabilize them and prevent tea from spilling out of these narrow-footed bowls. A tenmokudai is used to hold a contemporary appropriation of historical Chinese tenmoku by Japanese ceramist Furutani Noriyuki (b. 1984) (Fig 8).

Used in Japan since the sixteenth century, Korean teabowls are associated with a much different aesthetic language than Chinese tenmoku. Over time, Korean teabowls came to exemplify the aesthetics of humbleness and simplicity known as wabi. Tea master Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) particularly coveted select Korean vessels for their asymmetrical forms, roughly textured surfaces, and comparatively high, large feet.

One example of a Korean bowl of this aesthetic now in the University of Michigan Museum of Art collection may have been made initially for either food or tea (Fig 9). It was later repaired with lacquer covered by gold, in a process called kintsugi, literally "gold joinery." Its kintsugi suggests that it was used at some point for tea in Japan, where starting in the sixteenth century, kintsugi became a popular method of artfully repairing teabowls and other ceramics. The bowl and its kintsugi repair, both of which reflect the aesthetics of wabi, may have elicited for users a reminder to be free from attachment and seek an understanding of "true reality," a sentiment recorded in some historical texts connecting Zen and tea.

By the seventeenth century, Japanese tea practitioners began using more domestically made tea utensils often embodying the wabi aesthetics of simplicity, naturalness, and subtle imperfection. While early Japanese teabowls initially copied aspects of Chinese Jian ware teabowls, by the seventeenth century they tended to differ significantly from them with a larger size and a more diverse range of forms and designs. In contrast to Jian ware teabowls' symmetry and refined smoothness, Japanese versions featured straighter sides, broader bases, and surfaces with varied textures. The bowl named Eboshi exemplifies the wabicha ("rustic tea") aesthetics developed by generations of the Raku family, Japan's longest lineage of teabowl makers who forged close ties with Sen tea schools throughout their history (Fig 1).

While the three national categories form the foundation of teabowl aesthetics created and used in mainstream chanoyu practice today, contemporary ceramists around the world define and create teabowls using a wide variety of approaches that sometimes transcend traditional classifications. Since the 1960s in the United States, many ceramics students have been taught to approach the teabowl as an exercise in form. Some contemporary makers challenge utilitarian requirements or cultural precedents to pursue highly individualistic sculptural expressions. Ogawa Machiko creates vessels she titles not teabowls but simply "bowls" (wan, Fig 10). For a bowl made in 2008 she blended Shigaraki and Akatsu clays with metal oxides, then covered the bowl with white slip and clay and ash glaze, innovating the process beyond any single historical kiln style. She defines the teabowl as an "inclusive form" that one can "use freely as a vessel in a broad sense" and that "accepts everything—food, water, flowers, even your thoughts."

For anyone interested in teabowls, there is much to think about indeed. From their origins in China to their enduring role in chanoyu, teabowls represent complex intersections of culture, aesthetics, and artistic innovation. Through their forms and usage, teabowls invite us into multisensory visual, tactile, and contemplative engagements with chanoyu, revealing how a seemingly simple ceramic vessel can hold profound meaning.

References and Suggestions for Further Reading

Akanuma Taka. Chatō no sōsei: karamono kara wamono e [The creation of tea ceramics: from Chinese objects to Japanese objects]. Kyoto: Tankōsha, 2004.

Akanuma Taka and Tokyo National Museum, eds. Chanoyu: tokubetsuten / Chanoyu—The Arts of Tea Ceremony, The Essence of Japan. Tokyo: Tokyo National Museum, 2017.

Ching, Dora C. Y., Louise Allison Cort, and Andrew M. Watsky. Around Chigusa: Tea and the Arts of Sixteenth-Century Japan. Princeton, N.J.: P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art, Department of Art and Archaeology, and Princeton University Press, 2017.

Cort, Louise Allison. "The Kizaemon Teabowl Reconsidered: The Making of a Masterpiece." Chanoyu Quarterly 71 (1992): 7–30.

Cort, Louise Allison and Andrew M. Watsky. Chigusa and the Art of Tea. Washington, D.C: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2014.

Gotoh Museum and Tokugawa Museum. Chawan ni hana hiraku Momoyama jidai no bi [Master teabowls: the beauty of pottery in the Momoyama period]. Nagoya and Tokyo: Tokugawa Museum and Gotoh Museum, 2002.

Guth, Christine. "Import Substitution, Innovation and the Tea Ceremony in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Japan," in Global Design History, edited by Glenn Adamson, Giorgio Riello, and Sarah Teasley, 50–59. London/New York: Routledge, 2011.

Hayashiya Seizō. Meiwan wa kataru [On famous bowls]. Tokyo: Sekaibunka Publishing Inc., 2015.

Hur, Nam-lin. "Korean Tea Bowls (Kōrai chawan) and Japanese Wabicha: A Story of Acculturation in Premodern Northeast Asia," Korean Studies 39 (2015): 1–22.

Katayama Mabi. "Korean Tea Bowls and the Tea Ceremony," in Korean Art in the Freer and Sackler Galleries, 24–29. Washington D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2012.

Kemske, Bonnie. The Teabowl: East & West. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Morse, Samuel C. Fashioning Tradition: Japanese Tea Wares from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Northampton MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 2007.

Ohki, Sadako. Tea Culture of Japan. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2009.

Oka Yoshiko. "Wamono chawan to kindai no chanoyu" [Japanese teabowls and modern chanoyu]. Bijutsu Forum 21, no. 26 (2012): 94–100.

Pitelka, Morgan. Handmade Culture: Raku Potter, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2005.

——. "Form and Function: Tea Bowls and the Problem of Zen in Chanoyu," in Zen and Material Culture, edited by Pamela D. Winfield and Steven Heine, 70–97. Oxford University Press, 2017.

——. Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History and Practice. London: Routledge, 2003.

Watanabe Takeshi. "From Korea to Japan and Back Again: One Hundred Years of Japanese Tea Culture through Five Bowls, 1550–1650," Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2007): 82–99.

To cite this page:

Jones, Meghen. "How to Read a Teabowl." Teaching Tea: Culture, History, Practice on Japan Past & Present. 2025. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/teaching-tea-culture-history-practice-art/resources/how-to-read-a-teabowl-chanoyu-principles