In Search of the Truth: Historical Recordsby Angelika Koch

Fact, Fiction, and the In Between

While presenting a veneer of factuality, in reality true-record books belied their name by presenting a "semi-fictionalized" or "fictionally augmented" tabloid version of true events and real-life figures. Contemporaries were to some extent aware of the spurious and unsubstantiated nature of the claims made by these "manuscript books (kakihon)," as they were known at the time, with intellectuals voicing harsh criticism of the way they "made things up out of thin air" while "posing as actual records (jitsuroku-tai ni tsukuritaru)" and fooled the gullible "masses and women" into believing their entertaining version of events.

The kabuki playwright and publisher Nishizawa Ippō 西沢一鳳 (1802–1853) wrote in the mid-nineteenth century that "they all proclaim to be 'true tales, true tales (jitsusetsu, jitsusetsu to ari),' but in reality are mere conjecture (suiryō no setsu)," while also speculating that "some parts may be close to the truth (jitsusetsu ni chikakaran)."

Fact Check: Genta's Story

This mixture of fact and imagination in varying ratios is clearly a characteristic of Genta's tale. Some elements of our manuscript bear a distinct fictional stamp, such as the choice of Jizō as the tale's divine mouthpiece and the motif of the dream vision. The protagonist Genta, while a real-life figure, is presented as a paragon of beauty, virtue, and accomplishment rather than a flesh-and-blood young man.

Most importantly, the minutiae of his innermost thoughts, his intimate conversations, and the contents of his romantic correspondence to which no bystander would have been privy reveal the hand of an author filling narrative gaps and adding embellishment. At the same time, the plot remains plausible and lures readers into believing that they are being granted an exclusive peek into what might have happened—or perhaps even what really took place.

Hierarchies of Truth

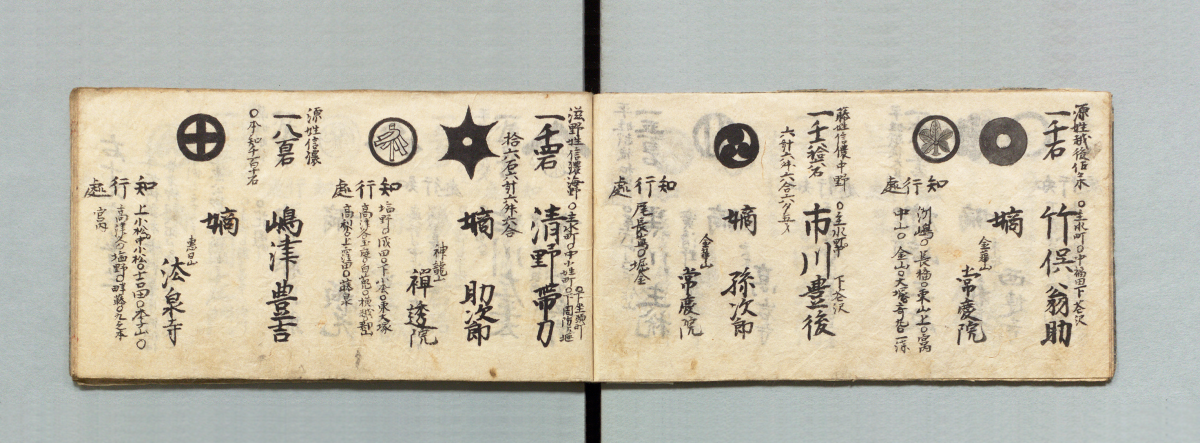

Yet despite such flights of fancy, the text is also cloaked in an air of official-record precision and authority—"posing as an actual record" of events, as Tachibana Nankei puts it. Appropriating many of the conventional tools of histories, chronicles, genealogies, and record-keeping, the manuscript names real-life actors and meticulously incorporates the precise dates and locations of events, lending it an appearance of factuality. It also creates a certain hierarchy of truths by interspersing the narrative with half-sized interlinear commentary that repeatedly recounts contemporary gossip (sezoku no sata) along with alternative interpretations of facts in miniscule lettering. By visually cordoning off these parts as (unreliable) word-of-mouth reports, such interjections also arguably serve to enhance the claim to truth and purported objectivity of the main text.

On the Record

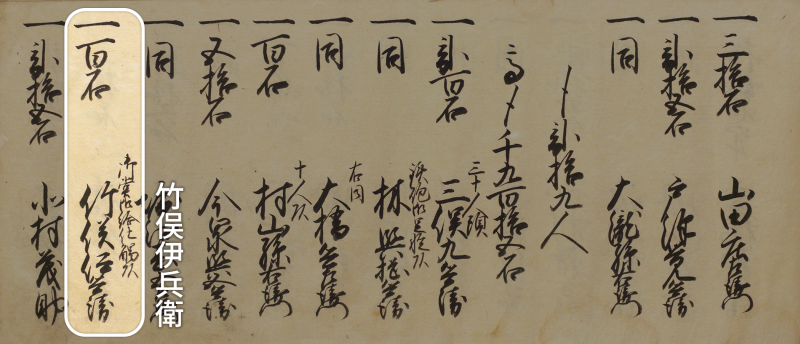

But what is the actual core of "truth," the seed of factuality from which this story grew? And how does our manuscript compare with available official versions of its history, compiled by the domain and its bureaucrats? The existence of most of the tale's long list of characters can in fact be confirmed from official domain records, such as genealogies and rosters of retainers.

The early death of Genta's father, for example, is historical fact rather than melodramatic device, as are Genta's pedigree, family stipend, date, location, and circumstances of death, along with inconsequential trivialities such as the death of another retainer soon after Genta's demise (who is promptly asked to put in a good word for Genta with the King of Hell in one of the manuscript's more fanciful flourishes). At the same time, the inclusion of such precise particulars suggests that the compiler of the text had access to this type of official information.

Tracing Genta's Murder

Various facts surrounding Genta's murder at the hands of a fellow samurai, the pivotal event that prompted the manuscript's compilation, can similarly be ascertained from a range of official documents. Thus, the chronicle Yonezawa shunjū 米沢春秋 reports tersely that

"on the first day of the tenth month of Shōtoku 3 (1713), Takenomata Genta and Nagai Seizaemon engaged in a private fight (shitō) in the alley east of Yamada's house in Minamiyachi-kōji."

The Uesugi family's genealogical records also provide insight into the official fallout from the attack—an aspect not covered in our manuscript—recording that roughly a month later

"on the fourth day of the eleventh month of Shōtoku 3 (1713) Nagai Seizaemon was beheaded and his family name thus discontinued for the murder of Takenomata Genta."

With bureaucratic brevity, these sources are primarily couched in official legal jargon, in which "private fights" was a term describing unwarranted samurai violence carried out for personal reasons, a phenomenon that the shogunate and domain authorities generally tried to control in order to maintain peace and social order.

The punishment meted out in this case—decapitation and discontinuation of the Nagai family name—was severe by contemporary standards. Samurai in the Edo period could be granted an honorable death sentence by ritual suicide (seppuku)—in reality no more than a ritualized beheading—to spare them the shame of public decapitation, an act of grace that was not extended to the culprit in this case;

Flipping the Record

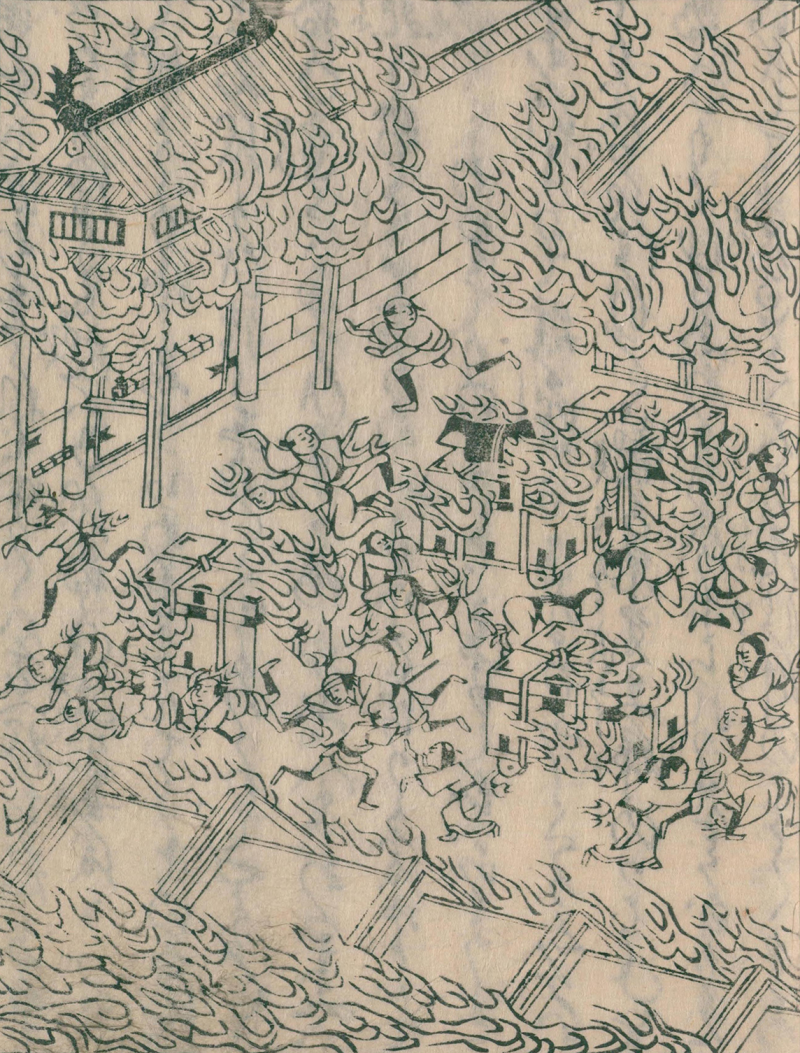

To an extent, it is ultimately a futile enterprise to try and prize fact from fiction in true-record books, since the way that news and information spread in the early modern period did not necessarily acknowledge such a clear-cut distinction. Peter Kornicki has previously pointed out that seventeenth-century Japanese disaster accounts of actual catastrophes display literary and narrative features, including anecdotes and humor.

It is therefore necessary to take into account the discrepancy between contemporary and early modern notions of factuality and to recognize that the line between (purported) fact and fiction could be highly porous in the early modern period, with true-event books commonly providing fodder for writers of popular illustrated fiction and plays, particularly from the late eighteenth century onward.

To cite this page:

Koch, Angelika. "In Search of the Truth: Historical Records." Blood, Tears, and Samurai Love: A Tragic Tale from Eighteenth-Century Japan on Japan Past & Present. 2024. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/blood-tears-and-samurai-love/introduction/in-search-of-the-truth

For additional information on references and images, see our bibliography and image credits pages. Research for this page was generously funded by the Dutch Research Council.