How to Win His Heart: Male-Male Love & Courtship Etiquetteby Angelika Koch

Genta's Love Troubles

Within the logic of the Yale manuscript, Genta's tragedy is primarily presented as the result of his poor romantic choices and the lack of guidance he receives on these matters from the older men in his life, who are repeatedly berated as "untrustworthy fellows" by the narrator. Seventeenth-century guidebooks on male-male love typically exhorted wakashū to choose an "older brother" wisely, using his character, reputation, sincerity, and knowledge of the ways of the world as a basis, since a poor decision would become a lifelong source of regret and lead to ridicule.

The strategies and ideals of "love" encapsulated in the manuscript—from the willingness of Genta's uncle and neighbors to arrange trysts to the demand by a lover for Genta to bind himself by an oath—may seem obscure and far from romantic to the modern reader. At the time, however, such courtship strategies were a normalized aspect of male-male relationships, particularly in the guidebooks to nanshoku etiquette that appeared in seventeenth-century popular print.

A Boys' Love Primer, Part 1

Poetic Letters and Trusted Go-Betweens

"Rather than visiting for a thousand days and ten thousand nights in an attempt to seduce him, a single verse will serve to soften his heart and make him feel deeply for you; such is the power of poetry." (Nanshoku masukagami)

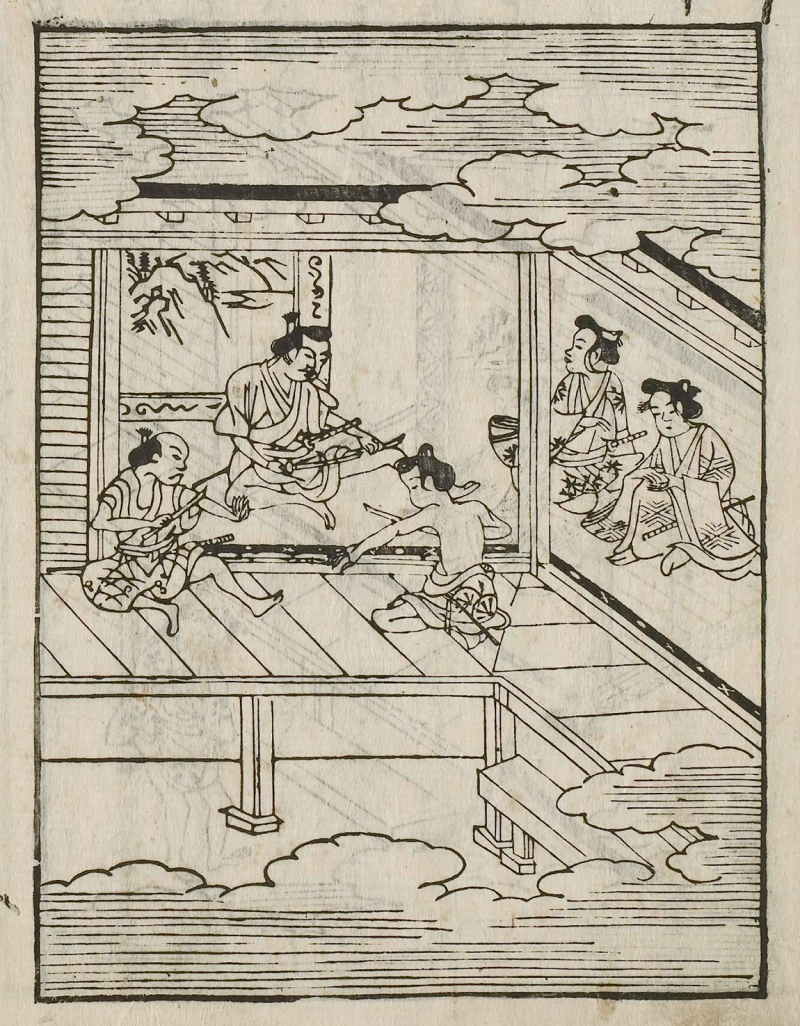

Male-male love may well begin with stolen glances and "adoring the wakashū's beautiful face from afar," but in order to strike up a relationship it was necessary to clearly convey one's feelings to the object of one's affections. For this purpose, etiquette books invariably recommended the use of go-betweens and love letters

As one guidebook observed: "In this refined way of the youth, relationships start from subtle allusions to one's feelings, which flower 'in stony silence like mountain azaleas' written all over a lover's embarrassed face without being spoken openly, and therefore the text [of a love letter] is of great importance."

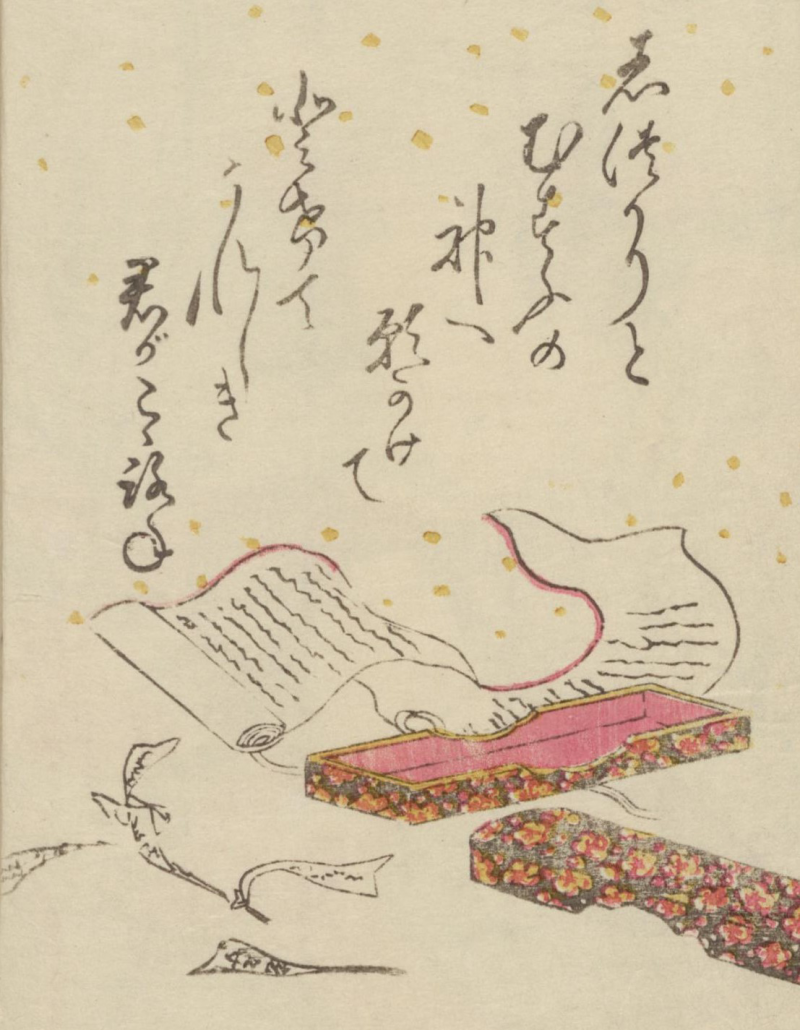

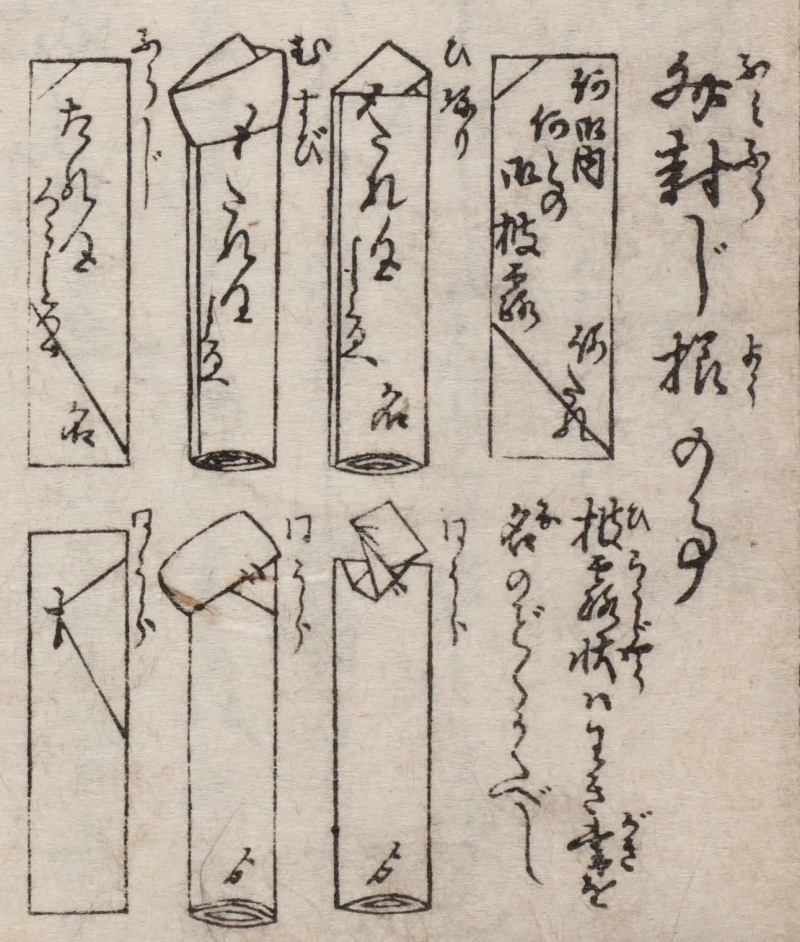

Love "Letteracy"

Male-male love epistles were thus part of what Laura Moretti has recently described as Japan's seventeenth-century "letteracy"— the complex set of skills involved in letter writing that required more than mere literacy—that readers could navigate with the support of a flurry of popular letter-writing manuals.

By the late Edo period, more risqué compendia of love letters provided not only correspondence samples for every conceivable type of partner and situation— from lady-in-waiting to sex worker and from first confession to break-up—but typically also included head texts that provided more explicit instructions for intimacy in the bedroom.

The Power of Poetry

It was widely assumed that waka poetry and poetic allusions were the appropriate means for expressing emotions in an elegant love letter, and for this purpose compendia of love letters might, for example, append a list of classical poems applicable to a variety of situations, such as writing a first letter, remonstrating with "a cold-hearted lover," and declaring one's "burning love" (kogareshitau uta) or "a love that is hard to forget" (wasuregataki omoi).

As the etiquette guide stressed, classical poetry (furuuta) and prose tales (monogatari) were the ultimate idiom of lovers, while the formal epistolary style (sōrōbun) that typified other forms of male correspondence risked putting off any "wakashū with a heart." Instead of the "stiff" (katai) formulaic phrases of the Sino-Japanese register, elegant and "gentle" Japanese words (Yamato kotoba) were to be preferred, although their excessive use was to be avoided for fear of straying into an all-too feminine style.

It is therefore not surprising that Genta in the Yale manuscript receives a poem in a love letter from his ardent admirer (and future murderer), although in this case it is an original, personalized verse that incorporates a word play on Genta's name, rather than a staple from the classical canon. As we have seen from their inclusion in early modern guidebooks on male-male courtship, waka were by no means the exclusive domain of heterosexual love, and the fact that by the seventeenth century a scholar of classical literature such as Kitamura Kigin 北村季吟 (1625–1705) was able to create a poetic tradition of male same-sex love demonstrates the malleability of various gendered readings of Heian poetry.

First letter to a youth:

"Even though I hide it, my longing must have shown all over my face, so that people even ask me, 'What are you thinking about?'" This took me by surprise, but given that it has come to this, I asked for this letter to be delivered and, despite my lack of skill, took up my brush to write to you. Ever since that time [Comment: Fill in the appropriate time here] when I laid eyes on your figure, as beautiful as Mishima Bay, deep feelings have colored my heart. I have to wind my dyed kimono sash three times around my waist as I am wasting away with longing, so that in the end it became obvious for everyone to see.But since this is an unattainable love, I do not dare to dream that my wishes might be fulfilled. […] I shall wait for a word from you in the hope that you will take pity on me. I merely seek to dispel the smoldering fire in my chest, which burns for you like the smoke that rises in the evening at Matsuo Bay. (Translated from Nanshoku masukagami)

Letter to reject an unwanted suitor:

I am grateful for your kind letters and for the great consideration and courtesy you have shown me. I have wanted to send a reply, but since this is a delicate situation… [...] You must rid yourself of any feelings you have for me, and I would be most obliged if you would do so. I am truly sympathetic to your feelings, yet however sorry I feel for you, we will never be together in this world. [...] Since this is how things stand, I hope that you will understand. [...] ["Even if you persist in sending me letters, I shall not respond"— if you send a letter like this, this is sure to put a stop to anyone making repeated advances.]

(Translated from Saiseiki)

The Art of Responding

Responding to letters required both tact and tactics on the part of the wakashū. The nanshoku guide Saiseiki 催情記 (ca. 1624–1644) provided instructions based on how the younger partner felt about the sender. If they had no interest in a relationship, then there was no need to reply. But if their admirer failed to take the hint even after their first three letters had been ignored and persisted in pleading "at least let me see your handwriting, so that I shall have something to worship," then it was time for a perfunctory but strongly worded response designed to quash their hopes once and for all (see the translation). If the wakashū shared the same feelings as the writer, the manual still advised against sending an immediate reply, but recommended prudently taking time to evaluate the suitor and the sincerity of his feelings.

A Boys' Love Primer, Part 2

Pledges on Paper, Promises in Blood

"Since it is customary in the way of male love to enter into a formal agreement (keiyaku) with rules, everyone exchanges written oaths (seishi) […]."

(Nanshoku masukagami)

The ultimate relationship goal as presented in etiquette guides was for the wakashū, after careful consideration of his suitor's intentions, to accept him as his "older brother" and exchange written vows.

Written vows thus aimed to limit the romantic range of both partners and represented a promise of fidelity and exclusivity. At the same time, it is clear from their content that they were designed to grant older partners a significant degree of control over youths and their movements, evoking Gregory Pflugfelder's characterization of such popular discourses on male-male love as a "literature of the nenja [older partner]."

Formal oaths were usually inscribed on a religious talisman in ink or blood and invoked a variety of gods (hence the request in the manuscript that Genta write an "oath to the gods") based on the premise that divine punishment would befall those who broke their pledge.

In some cases, however, proof of one's love could take more extreme forms than written vows and included severing a finger, ripping out a fingernail, and cutting oneself on the thigh or upper arm with a blade. Some nanshoku guides even provided detailed advice on how best to carry out such actions without crippling oneself for life.

To cite this page:

Koch, Angelika. "How to Win His Heart: Male-Male Love & Courtship Etiquette." Blood, Tears, and Samurai Love: A Tragic Tale from Eighteenth-Century Japan on Japan Past & Present. 2025. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/blood-tears-and-samurai-love/introduction/how-to-win-his-heart