Brave and Beautiful Boys: Samurai and Same-Sex Cultureby Angelika Koch

Publishing "Male Love"

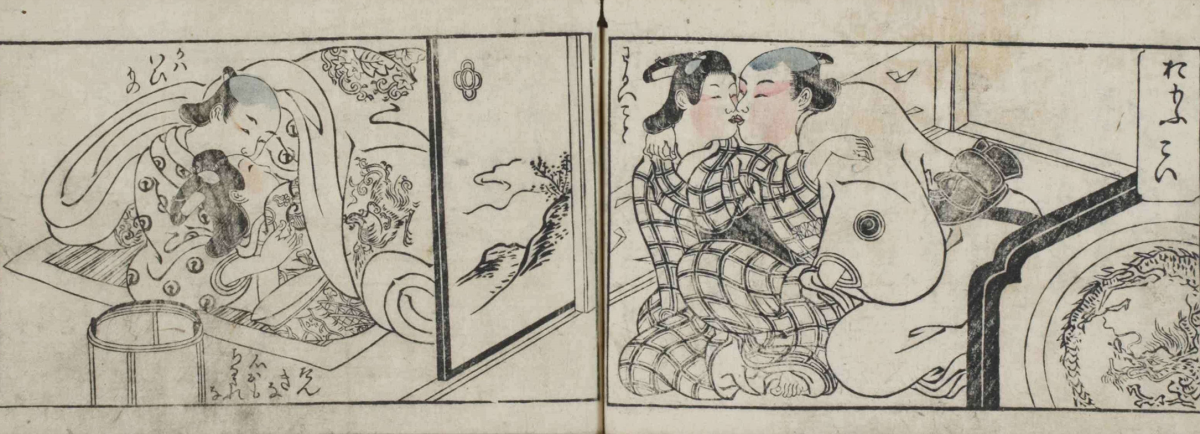

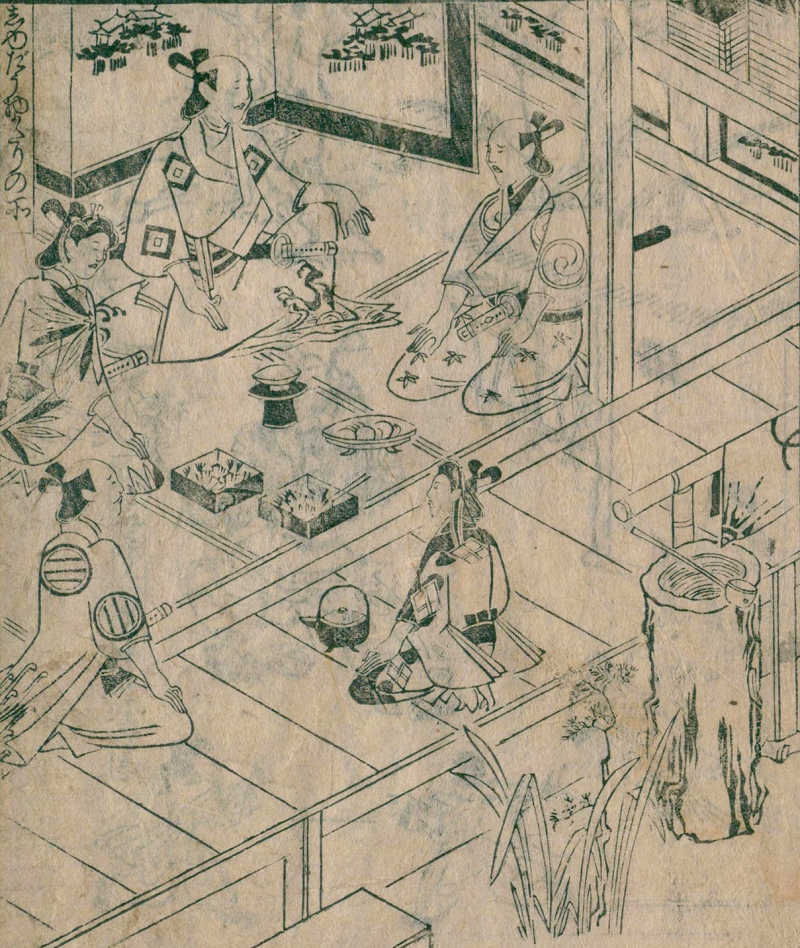

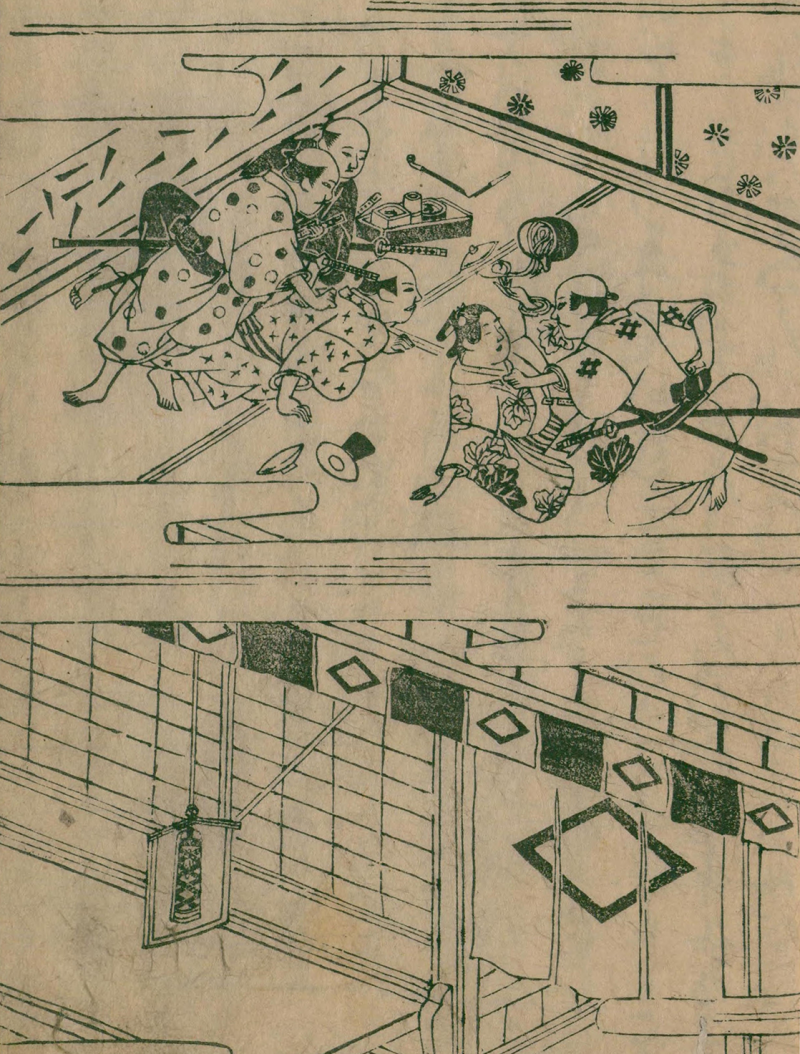

By the time the Yale manuscript appeared in the early eighteenth century, a commercialized popular culture had developed around "male love" (nanshoku), or the "way of the youth" (shudō), in the metropolises, fueled by a booming publishing industry, male prostitution, and the popularity of kabuki theaters with their casts of all-male actors. As such, the subject was openly thematized in commercial print, with various guidebooks detailing the intricacies of male-male love, from advice on writing love letters to the mundane practicalities of plucking nose hair. There were also fictional disputes published about the superiority of "male love" over love for women, actor evaluation books that reviewed the physical beauty of young men on the kabuki stage, and collections of love stories that featured monks, actors, and loyal samurai youths, as well as explicit shunga books with illustrations of male couples. Legal pronouncements at the time primarily sought to regulate the potential fallout from intense male-male bonds rather than targeting the practice itself, while medical discourses made little objection on health grounds and remained largely silent on the subject.

If the Yale manuscript's contents were potentially problematic and unsuitable for publication on a number of counts (see Introduction section 2), nanshoku was therefore unlikely to have been one of them. Its attributed title aside, the text does not in fact apply this specific label to the protagonist Genta's various amorous exploits, referring instead to the bonds between the male characters in terms of "infatuation" (shūshin) and "intimate friendship" (kon'i). Yet it is clear that male-male relationships occupy center stage and form the unifying logic and driving force behind the events that unfold. The work thus warrants inclusion in the diverse corpus of nanshoku-related texts from the Edo period but also raises the question of where it sits within it.

As a manuscript from a remote northern domain, how does it compare with the commercially published models of urban male-male love? How does it fit within possible local constellations of male same-sex culture? And what points of contact might there be with literary and legal discourses, as well as with other "clandestine," scandalous texts on male-male love?

Gallery: Nanshoku Publications

Explore below what kind of texts about male love were available in print.

Of Monks, Samurai, and Beautiful Boys

Nanshoku had already played an important part in Japanese culture and literature prior to the Edo period and had long been associated with religious and political elites, particularly the samurai class and the Buddhist clergy. Medieval Buddhist monasteries housed a number of adolescent acolytes (chigo), who studied and served under senior monks, fulfilled ceremonial and ritual functions, and also acted as sexual and romantic partners for their superiors.

By the early Edo period, the Buddhist clergy were routinely depicted as lovers of boys in humorous tales and other popular fiction. Against this backdrop, the Yale manuscript's choice of a Buddhist deity as narrator, as well as a Buddhist monk as the (purported) compiler who laments Genta's death, may not be coincidental—although clerics do not feature among Genta's many lovers and admirers.

Instead, Genta's admirers hail from a warrior background, a social class closely associated with intimate male-male bonds from the medieval period onward.

Unofficial accounts of the much-maligned shogun Tsunayoshi 徳川綱吉 (r. 1680–1709) allege that he drafted handsome retainers as personal attendants, which prompted young men to adopt an unattractive hairstyle humorously termed "avoidance hair" (yokebin) in an attempt to diminish their physical charms and escape his attentions. If one is to believe a collection of character sketches of daimyo compiled around 1690 (Dokai kōshūki 土芥寇雠記), 37 out of the 243 regional lords were "too amorous" in their pursuit of men;

What nanshoku shared across these various social settings was the preference for a wakashū or adolescent youth—be they acolyte, page, young samurai, actor, or male prostitute—to act as the younger partner for an adult male (nenja). Genta is clearly represented as a wakashū in the Yale manuscript's illustrations, sporting the maegami hairstyle with forelocks that was typical of youths who had not yet undergone their coming-of-age ceremony. Genta, who we learn at the time of his murder had been preparing for his preliminary coming-of-age ceremony (hangenpuku), becomes the primary object of the adoring, adult male gaze in the story—not only that of his numerous lovers but also of the narrator Jizō and the anonymous monk-compiler. He stands at the center of the narrative, which turns a real-life murder into the tragic tale of its young victim rather than that of the murderer, Nagai. As such, Genta is presented in a somewhat idealized and appealing light as a highly talented adolescent samurai of good character, a feature the manuscript shares with wakashū-centric literary texts. Apart from a single love poem lauding his "peerless beauty," however, virtually no reference is made to his physical attributes, and the manuscript largely forgoes lyrical and literary devices in order to strike a more factual-sounding tone.

Uesugi Lords as Boy-Lovers?

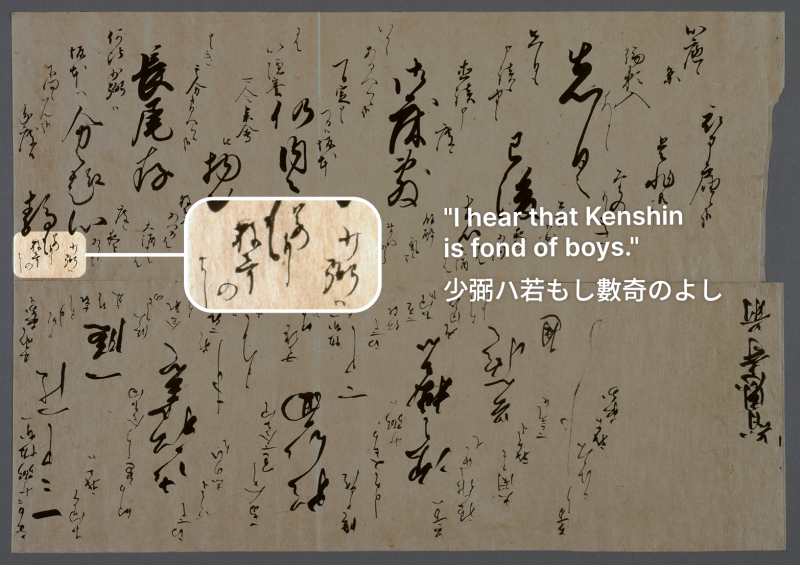

But how does the Yale manuscript fit into the context of a possible local culture of samurai "male love" in Yonezawa, and what traces of such a culture survive in the documentary record? Beginning with the highest ranks of the samurai hierarchy, it appears that some heads of the Uesugi family were known for their alleged fondness for boys, with the famous warlord Uesugi Kenshin 上杉謙信 (1530–1578), the progenitor of Yonezawa's Uesugi daimyo, rumored to be a lover of beautiful youths. In a letter dated 1559, the imperial regent Konoe Sakihisa 近衛前久 (1536–1612), who became one of Kenshin's close allies, commented on the latter's reported "penchant for youths" (wakamoji-suki), remarking that during his stay in Kyoto the warlord repeatedly attended banquets that involved heavy all-night drinking in the company of "many beautiful boys" (kyamoji naru wakashū).

The first daimyo of the Yonezawa domain, Uesugi Kagekatsu 上杉景勝 (1556–1623), was the object of similar gossip. A miscellaneous collection of historical anecdotes and local hearsay from northwestern Japan, compiled by a doctor from Echigo in 1690, depicts Kagekatsu as a consummate woman-hater. It claims that Kagekatsu despised women to the extent that he would not tolerate their presence and even avoided his wife, which raised concerns about the succession of the fledgling domain among his loyal retainers. As a result, Naoe Kanetsugu 直江兼続 (1559–1620), one of Kagekatsu's chief advisers, devised a ploy to secure an heir by dressing up a Kyoto prostitute as a beautiful boy.

Banning "Male Love:" Yonezawa Domain Law

While such rumors show how male bonds at the very top of samurai society were viewed from below, domain decrees relating to nanshoku encapsulate the regulatory, top-down view of the Yonezawa domain authorities in their attempts to rectify perceived issues among their retainers. In this regard, it is clear that the Yonezawa authorities were concerned about intimate ties between samurai as early as 1603 when they issued a ban on bonds "with young men among one's colleagues, let alone those from another household."

Against the backdrop of domain-building by the Uesugi after their recent move to Yonezawa, this ban was part of more far-reaching efforts to limit fraternization with other military houses. Thus, rather than any moral qualms about same-sex relationships, what appears to have disconcerted the authorities was their "political" potential to "form cliques" (totō) and strong allegiances between retainers that could endanger the hierarchical social fabric of the domain.

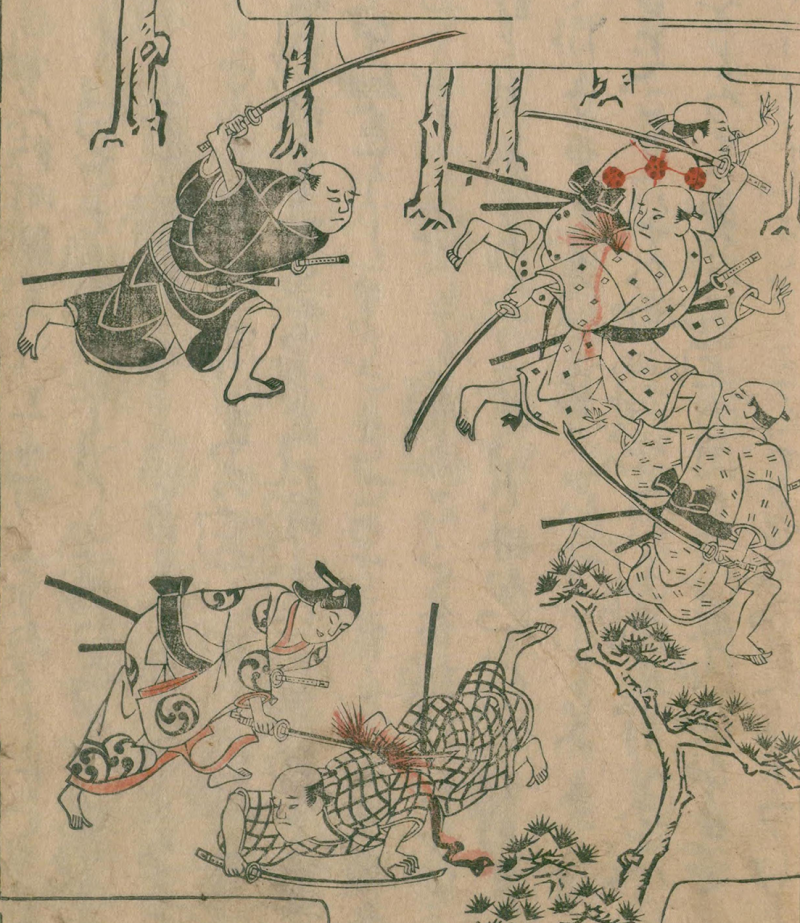

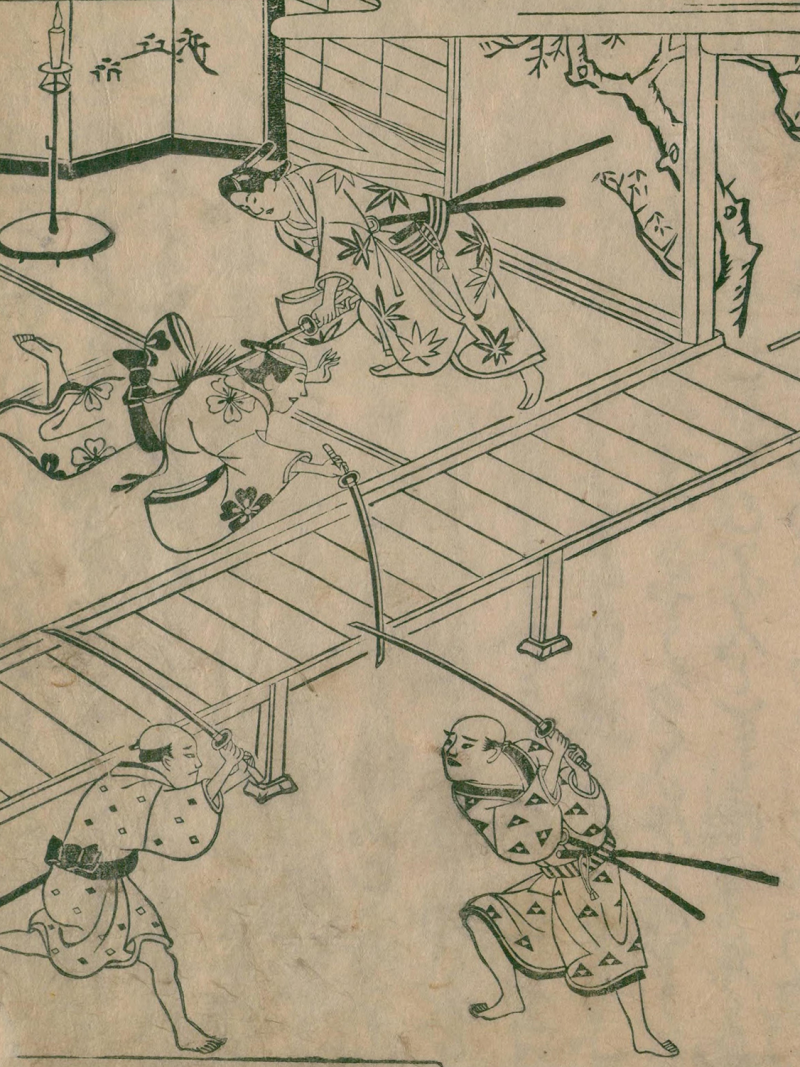

Subsequent decrees throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries reiterated this theme, while also seeking to suppress the excessive and violent behavior that accompanied nanshoku relationships. This included participation in the "violent craze for boys" (1656) and all the "recent shudō incidents in various neighborhoods" that fomented disagreements, disturbances, and discord in the whole community, resulting in "matters of life and death" (1775).

While such official regulations naturally focus primarily on the darker, more violent side of nanshoku, it is hard to ignore the parallels with Genta's tale. "Cliques" of lovers and enemies are formed and loyalties are reshuffled based on Genta's intimate bonds with other men, which are openly brokered by friends, neighbors, and acquaintances acting as matchmakers. Intimate relations quickly sour and become a source of jealousy and discord within the neighborhood circle of mid-ranking retainers, ultimately becoming "a matter of life and death" for Genta.

The progression of Genta's nanshoku relationships, in fact, closely matches that of shudō pronouncements in domain legislation. Viewed together, these local decrees and the Yale manuscript evoke a lively, communally condoned yet potentially violent local culture of samurai male-male love. Within this context, Genta's case may well have been precisely one of the nanshoku-related incidents that the authorities were anxious to prevent.

Murderous Intentions

Despite the fact that some prohibitions were ostensibly drawn up in response to actual nanshoku incidents, extant domain case records provide no specific category for such occurrences and—as in official reports on Genta's case—do not routinely cite motives for crimes.

One rare instance from the domain's collection of legal precedents notes a 1719 incident in which a page at the Uesugi's Edo mansion in Shirogane killed his servant and one of his colleagues in a fit of "insanity" (ranshin) for nanshoku-related reasons. The punishment was the same as for Genta's murderer, namely decapitation and discontinuation of the family name, which suggests that domain authorities in the early eighteenth century took a firm stance against violent expressions of same-sex relations among their mid-ranking retainers.

The only other detailed account of a comparable murder case comes from an unofficial source, a manuscript miscellany of local incidents and anecdotes, and concerns the 1767 case of Hirabayashi Rikisuke 平林力助 (24) and Nakazato Heiji 中里兵次 (13), who had "sworn an oath of brotherhood" sealed in blood.

As in Genta's case, this incident involved mid-ranking (yoita) retainers of the Yonezawa domain, and it illustrates the intense rivalries and coercion that could occur in this milieu for the favors of a good-looking adolescent boy. At the same time, the report demonstrates the importance of nanshoku relationships for socializing and networking among samurai youth, while also suggesting the deep-rooted nature of such practices—to the extent that senior figures in the community, such as Heiji's father and the elderly acquaintance who petitions Genta on behalf of Gōhachi, appear to have accepted the legitimacy of such relationships and been actively complicit in enabling them.

To cite this page:

Koch, Angelika. "Brave and Beautiful Boys: Samurai and Same-Sex Culture." Blood, Tears, and Samurai Love: A Tragic Tale from Eighteenth-Century Japan. Japan Past & Present. 2024. https://japanpastandpresent.org/en/projects/blood-tears-and-samurai-love/introduction/brave-and-beautiful-boys

For additional information on references and images, see our bibliography and image credits pages. Research for this page was generously funded by the Dutch Research Council.