Hidden Christians & Oral History: Practicing the Work of Love

Save PDFLesson Plan: Practicing the Work of Love [Interview 4: Nakamura Mitsuru]

Created by: Gwyn McClelland, University of New England; (assisted by Nobuko Sakatani and Satsuki Osaki, Gotō Islands)

Creation date: January 23, 2024

Keywords: World Heritage, Names, Discrimination, Consciousness, Identity

Interview 4: Nakamura Mitsuru

Target Audience:

Undergraduate students, Graduate students

Duration:

1 hour, not including reading time

Learning Objectives:

To discuss and conceptualize subjectivity and intersubjectivity in the oral history interview. First, read Lynn Abram's essay on "subjectivity and intersubjectivity" in her book, Oral History Theory.1 What is necessary in order that Nakamura's personal subjectivity can be understood as a strength in his interview?

To assess how historians make generalizations from oral history data. Trevor Lummis argues that "the problem at the heart of using the interview method in history still remains that of moving from the individual account to a social interpretation."2 See his chapter on this topic in The Oral History Reader (2nd Edition), Chapter 20: "Structure and Validity in Oral Evidence." Having established that subjectivity can be a strength in Objective 1, on what basis might Nakamura's interview contribute to generalizations about Hidden Christian history? Discuss, commenting on structuring of interviews, representative samples, "silences" in narratives, and reliability of individual narration.

1 Lynn Abrams, (2016). Oral History Theory (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315640761.

2 Trevor Lummis, "Structure and Validity in Oral Evidence," in Perks and Thomson, The Oral History Reader, 2nd Edition, Routledge, 2006, 255.

Potential Courses to Include this Lesson in:

Oral History

History

Japanese Studies

Asian Studies

Religious Studies

Required Materials:

interview (including audio stream), and photographs

associated readings

teaching guide/lesson plan

Activity/Procedure:

In preparation for the class first listen to Interview 4, and study the transcripts, referring to the vocabulary list as useful. Discuss your impressions of the interview as a class. Then, read the background information in this teaching guide. In small groups, discuss the learning objectives. There are further questions for discussion at the end of this guide.

Background:

Introduction to Interview:

Nakamura Mitsuru was born on Hisaka Island in 1957, and when I visited he was the parish priest of Fukue Church, in Fukue, the castle town on the largest island of the Gotō. After the interview, he took me to the Dozaki Church Museum on the north-east of the island, a location from which much of the missionary work in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries took place, to the islands. Within the interview excerpt, Nakamura discusses the French missionaries who arrived in Nagasaki in the 1860s, his three young ancestors who died at Rōya no Sako, and an abrupt turn around, that he believes reversed many years of discrimination, after a fire in Warabi, a Buddhist village, that he observed on Hisaka Island as a junior high schooler.

Subjectivity and intersubjectivity

What does the interviewee's subjectivity reveal itself in this interview? For example, Nakamura is not so concerned with fact such as the years when things happened. He is not sure, for example, in what year the fire at Warabi occurred. However, he is very concerned about the meaning of that event, which in his own mind, precipitated a healing of the relationships between the descendants of the Hidden Christians (or Catholics) and other Buddhist populations on the island.

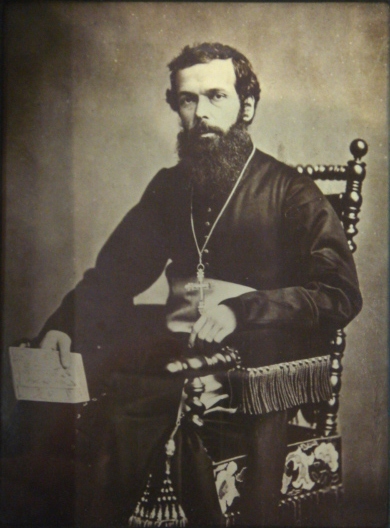

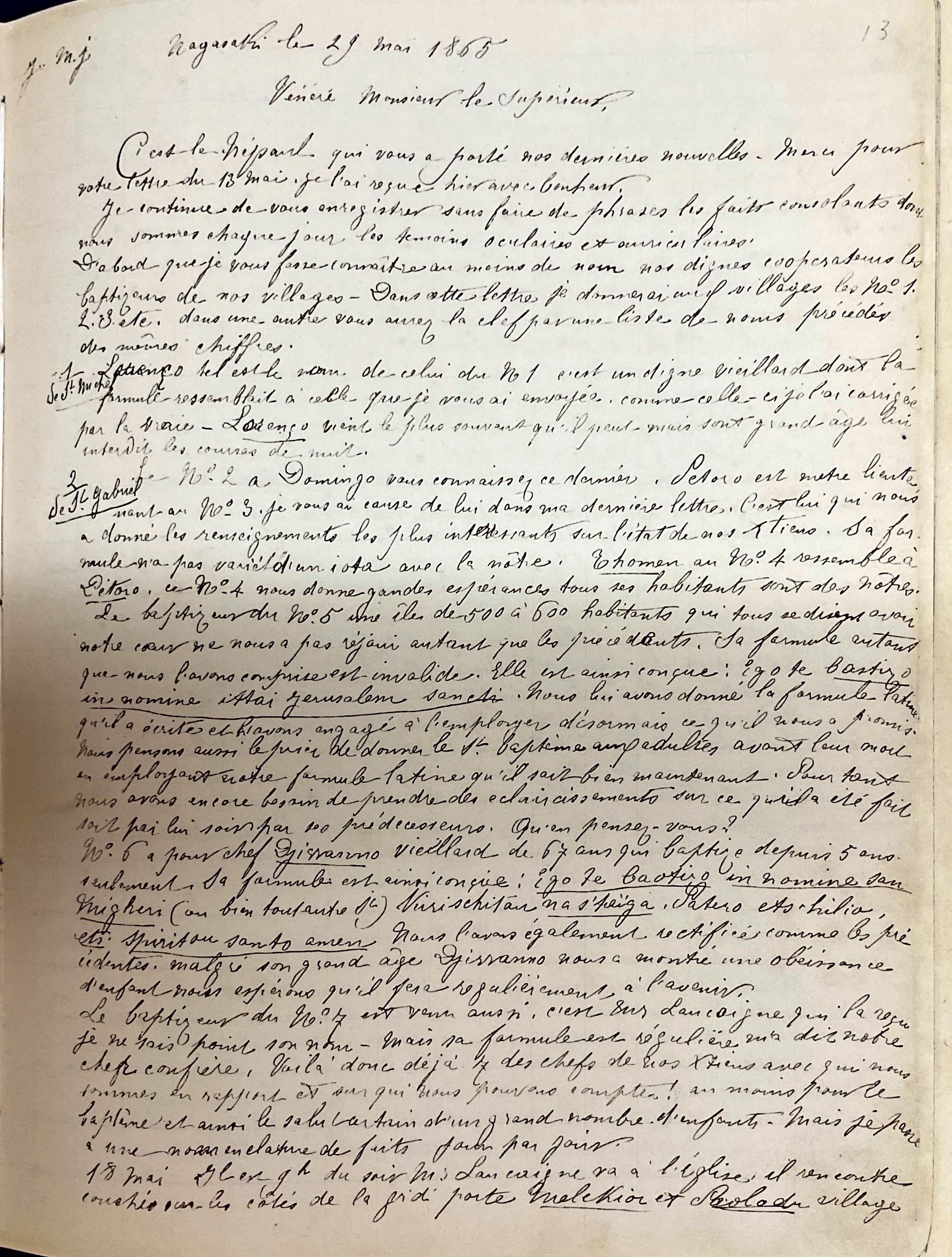

Nakamura says in the interview that a delegation from Hisaka Island visited the Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris missionary French priest Bernard Petitjean in Nagasaki and this is noted in some papers that are today held in the Junshin University Museum. The group visited him in 1865 and the above photograph was taken in approximately 1866. By cross-checking these diary/papers, the プティジャン書簡 (Petitjean Papers) that were written in French, we may imagine how this experience was understood from the perspective of the French missionary, Petitjean. It is imperative to refer to the literature in order to clarify, or to confirm aspects of the history. According to these papers, on the 8th May, Petitjean first mentions the G. Islands, as a place the missionaries should visit, as he has heard of the Kirishitan (Christians) with "the same hearts as ours" here. He again mentions the islands on the 29th May as in the excerpt below. Can you, or a friend who reads French, confirm the comments that Petitjean makes about the islanders? What else can we read into this?

In oral history it is important to corroborate evidence from an oral history interview with the wider literature. Also, by investigating other interviews, or discussions in the media that the interviewee has been involved in, it is possible to find out more about the subject.

In this interview's case, another corroborating document that is not included on this site describes some further thoughts of Nakamura's about his inheritance of the traumatic history of the Rōya no Sako on Hisaka Island. This incident is also mentioned in the Miyamoto couple's interview. The additional information about Nakamura's testimony is written in a Japanese language document named: [Kiri shō kyōku/ Kirishitan no kokoro wo shiru: Gotō junrei mukashi katari: Kiri Parish / Knowing the hearts of the Kirishitan: The old stories of Gotō Pilgrims], in fact another oral history from 2002. In this document Nakamura Mitsuru's own statement is included about his familial history. Nakamura writes in this document in an introductory comment as the Chairperson of the NPO Nagasaki Junrei Pilgrimage Centre, and as a practicing Catholic priest.

As you will see in the interview, Nakamura's great grandfather was born after the 1868 Rōya no Sako incident. His great grandfather's three elder sisters, however, all died as "martyrs" in the jail persecution event.

In the 2002 document Nakamura wrote:

…when people who are not Catholic hear about this incident, they ask me: "Wasn't the mother in utter pain due to the cries of the child who really didn’t understand what was going on?" It is a really difficult question to answer, but I think that at the time the mother's feeling was that they had faith that the child would be able to go to heaven, and so that is what I say and so, that was the Catholic believers of the time's utmost choice, I reply. This proposal never seems to convince the questioner, though.

But the fact is, the mother of the three girls [who died], my great-great grandmother, in her later years, said: "When my children died in the Rōya no Sako, I did not cry. However, as the years went on, my tears spilled over.", as I understood it. […] Surely, my [great-great] grandmother's flowing tears could not be any less than a strength of witness given by God, that is how I think of it.

Cathy Caruth, trauma studies scholar, writes that "…in trauma the greatest confrontation with reality may also occur as an absolute numbing to it…" – and that this may lead to an inability to witness the event as it occurs. Referring to Sigmund Freud, she continues by writing that for those who undergo trauma, it is not only the moment of the event, but the passing out of it that is traumatic: "survival itself can be a crisis." The mother of the three girls remembered in this way her experience of trauma at the treatment and loss of the children through the generations to her great-great-grandson, Nakamura.

Discussion Questions:

Can you identify any moments of "intersubjectivity" evident in this interview extract? What aspects reflect "performance" by the participant(s)? Explain why.

Can oral history be collaborative? Explain what would be necessary, considering the five interview abstracts, and the intersubjective process of interviewing.

Evaluation:

Students should write a short piece about how they understand the importance of subjectivity and intersubjectivity in oral history, and in this specific interview with Nakamura Mitsuru.

Other Sources/References:

Abrams, Lynn (2016). Oral History Theory (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315640761.

Caruth, Cathy. Trauma: Explorations in Memory (Baltimore and London: JHU Press, 1995.

Lummis, Trevor. "Structure and Validity in Oral Evidence." In Perks and Thomson, The Oral History Reader, 2nd Edition, Routledge, 2006.

Perks, Robert; Thomson, Alistair Scott. (Eds) (2006). The Oral History Reader (2nd ed.). London UK: Routledge.

Reference Images for Use:

View from Onidake on Fukue Island, you can see Fukue town on the left. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

View from Onidake on Fukue Island, you can see Fukue town on the left. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, 2022.

Bernard Thaddée Petitjean, (14 June 1829 – 7 October 1884) Photograph at the MEP, by PHGCOM, cc 1866, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bernard Thaddée Petitjean, (14 June 1829 – 7 October 1884) Photograph at the MEP, by PHGCOM, cc 1866, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bernard Petitjean's French language diary/papers of 29 May 1865. Photograph with permission of Junshin University Museum by Gwyn McClelland, October 20, 2023.

Bernard Petitjean's French language diary/papers of 29 May 1865. Photograph with permission of Junshin University Museum by Gwyn McClelland, October 20, 2023.

Rōya no Sako site on Hisaka Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, November 2022.

Rōya no Sako site on Hisaka Island. Photograph by Gwyn McClelland, November 2022.

Credits/Acknowledgements:

Credit to Nakamura Mitsuru for the interview. Thanks to the Junshin University Museum for allowing the use of the diary segment from Petitjean's Papers. Also, thanks to Ryo Sasaki (Fukuoka), and Akira Nishimura (University of Tokyo) for their support in this project.